SAN DIEGO — Charles Jackson French died young, his World War II heroism mostly forgotten, even in the place he called home: San Diego.

Now, 80 years after the Navy petty officer swam hours through shark-infested waters, towing a raft holding 15 injured shipmates to safety, he’s getting his due.

This story is for subscribers

We offer subscribers exclusive access to our best journalism.

Thank you for your support.

His name adorns a pool at Naval Base San Diego that’s used to train rescue swimmers, and it’s on a post office branch in Omaha, where he lived before joining the service. He’s been awarded a posthumous Navy and Marine Corps Medal, the highest award for non-combat valor.

All of that happened in the last year through the efforts of a swimming historian in Florida and others — including the daughters of one of the raft survivors — who believe French had been denied proper recognition because he was Black.

“I would be remiss if I didn’t acknowledge that Charles French was an African American serving at a time when prejudice and discrimination were ever present in our Armed Forces and society, which makes this recognition of [his] heroic actions even more significant,” said Capt. Ted Carlson, commander of Naval Base San Diego, during the pool dedication ceremony in May.

There have long been concerns about bias in the awarding of military medals. Earlier this month, the White House announced that a Black Vietnam War veteran first nominated for the Medal of Honor in 1965 would finally receive it.

In 2014, two dozen Army veterans dating back to World War II were awarded the Medal of Honor after a 12-year Pentagon review concluded they had been overlooked because of their race.

Some people are pushing for French to receive the medal, too. The nation’s highest honor for combat bravery, its 3,515 recipients since the Civil War include 93 Black people.

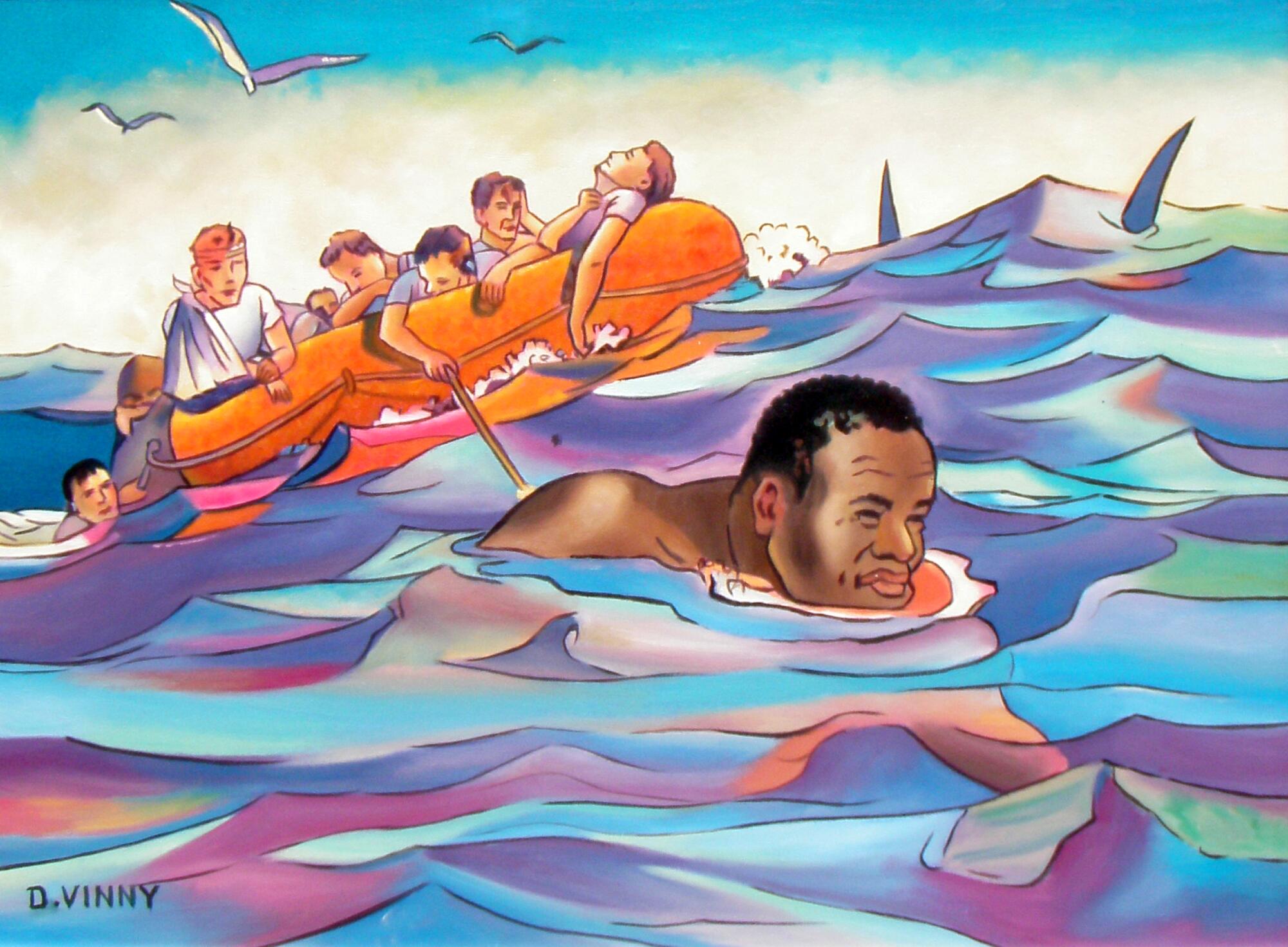

His relatives are pleased by the attention, which continues to spread via the internet with news stories, podcasts, even a painting done by an artist in Houston that depicts French as Poseidon, trident in hand, punching a shark.

“It’s been nice to see him finally get the recognition he deserves,” said Chester French, a nephew who lives in Omaha. “The key thing is, it’s a story that should be known across the country. He was a hero. And people don’t know it.”

A long swim

Charles Jackson French was born Sept. 25, 1919, in Foreman, Ark., and moved to Omaha to live with a sister after their parents died. He enlisted in the Navy shortly after turning 18.

He was a mess attendant, one of the few jobs available to Black sailors. He served meals to White officers, cleared their tables and washed their dishes. His four-year enlistment ended in November 1941. A month later, four days after the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, he signed up again.

On Sept. 5, 1942, French was on board the Gregory, a destroyer-turned-transport, which was patrolling waters off the Solomon Islands. Shortly after midnight, the ship was spotted by Japanese destroyers, which opened fire. Soon the Gregory was dead in the water and began to sink.

Ordered to abandon ship, injured crew members floated in the water while the Japanese zeroed in with search lights and machine guns. French began piling other sailors into a raft, according to an account later recorded by Ensign Robert Adrian, who was among the wounded.

Fearful that the currents would carry them to a nearby island and into captivity, French tied a rope around his waist and began swimming in the other direction. Adrian warned him about sharks that could be seen circling, but French said he was more worried about the Japanese.

“Just keep telling me if I’m going in the right direction,” he was quoted as saying.

He swam, by some accounts, for six to eight hours. An American scout plane spotted the raft and sent a Marine landing craft to take them to shore.

Six weeks later, Adrian went on an NBC radio program called “It Happened in the Service” and told the story of the sinking and rescue. “I can assure you that all the men on that raft are grateful to mess attendant French for his brave action off Guadalcanal that night,” Adrian said.

The Associated Press picked up the story, and a bit of celebrity followed French home. He was dubbed “The Human Tugboat.” Creighton University in Omaha honored him at halftime of a football game. He participated in war-bond rallies.

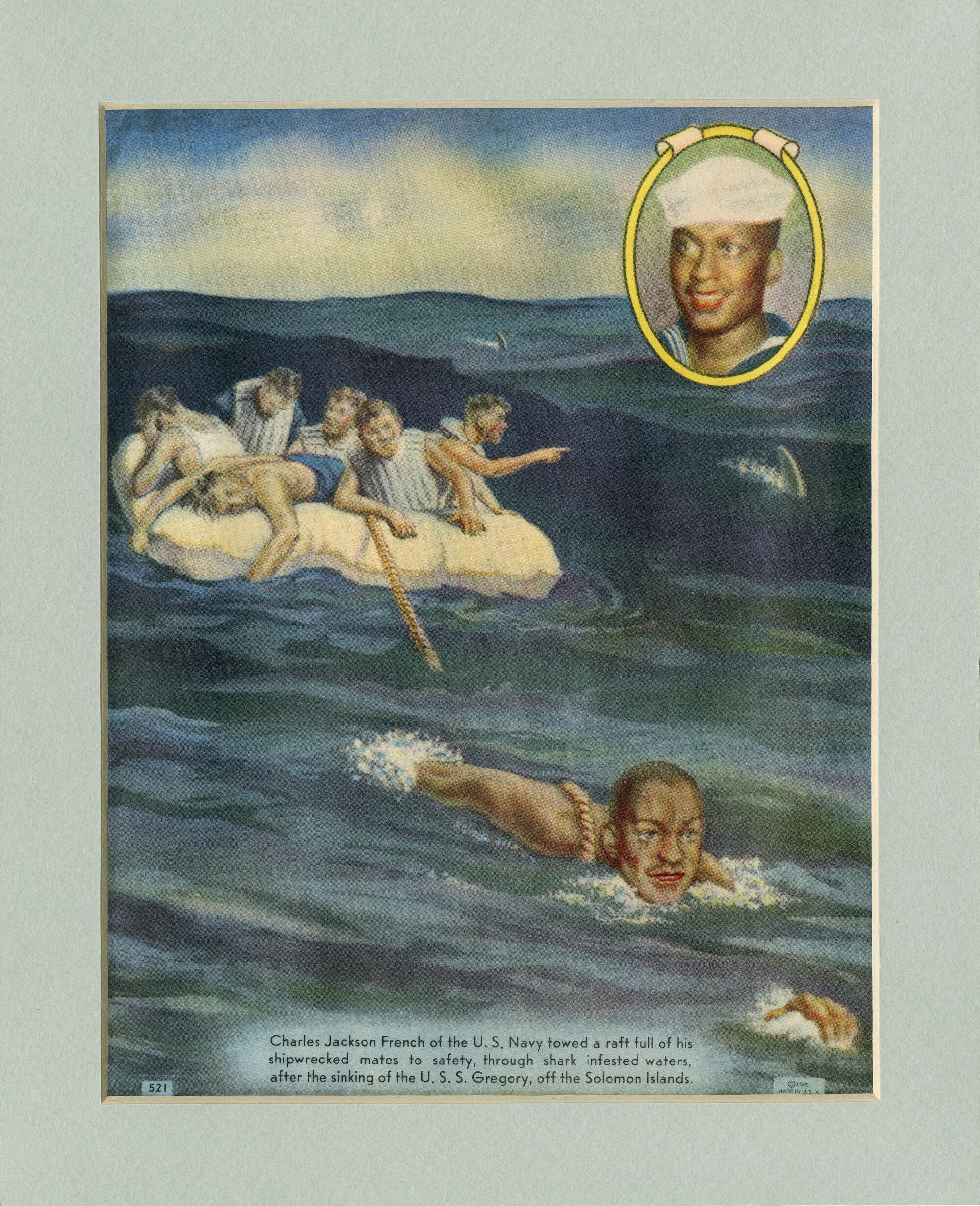

He was featured on a wartime trading card under the heading “Negro Swimmer Tows Survivors.” It had a drawing of him and the raft, with two shark fins knifing through the water. The text on the back identified him as a “mess attendant known only as French.”

True Comics, which ran in newspapers, did a 12-panel retelling of the story. A calendar spotlighted him. William Rose Benét, a Pulitzer Prize-winning poet, penned an ode called “The Strong Swimmer.” There was talk of Hollywood making a movie.

Black newspapers trumpeted a sailor who, in the words of one, “risked death that others might live” — and noted that the “others” in this case were White. That kind of selflessness, the Pittsburgh Courier wrote, “will make democracy a glowing reality in this country for future generations to enjoy.”

Not everyone was that impressed. Adrian had recommended French for the Navy Cross, the second-highest valor, but his bosses went in the other direction. There was no medal, just a letter of commendation.

The story faded away.

After the war, French settled in San Diego, which he apparently knew from his Navy training. He and his wife, Jettie Mae Anderson, had a daughter. He worked at the Navy Electronics Laboratory in Point Loma and lived in the Stockton neighborhood.

The major newspapers here, the San Diego Union and the Evening Tribune, apparently were unaware of his presence. There were no feature stories about him or what he’d done during the war.

His family said his war experiences left him with post-traumatic stress disorder. He drank heavily.

On Nov. 7, 1956, Charles Jackson French died and was buried at Fort Rosecrans National Cemetery. He was 37.

‘Wronged, wronged, wronged’

When Bruce Wigo began running the International Swimming Hall of Fame in 2005, he noticed something missing. Where was the history of Black swimmers?

He knew there was a rich one, dating back to observations Benjamin Franklin had made about their prowess in the water. So he set about to rectify the omission.

Nosing around on the internet, he came across a mention of the wartime trading card that featured French. He tracked down a collector who had one and got a scan of it.

Then he found French’s service records in a genealogical database. He found stories about him in the archives of Black newspapers. He learned about the radio broadcast and about a book, “Black Men and Blue Water,” that includes a chapter about the raft rescue.

“It was just one of those stories that captivated me,” Wigo said. “I was kind of blown away by it.”

He put French in an exhibit about Black swimmers at the museum in 2009 and continued to collect information about him. A retired Navy couple, Kevin and Kim Mickna, had been researching French, too, and pointed Wigo to Judy Decker, one of the children of Adrian. Growing up, she had heard all about the sailor’s heroics.

“My father thought of Charles French as his guardian angel,” Decker said. “He had a wonderful life, but he believed that none of it — including us children — would have happened if he had not been saved.”

Adrian spent many years trying to find French and get his Navy commendation letter upgraded. “My dad thought he had been wronged, wronged, wronged,” Decker said, “and a whole lot of it had to do with his race.”

Before he died in 2011, at age 91, Adrian asked his children to pick up the torch of remembrance. “Any time we had the opportunity to talk to someone in the Navy, we did,” said Decker, who lives in Annapolis, Md., home of the U.S. Naval Academy.

In Omaha, Chester French was trying to keep the story alive, too. French’s nephew grew up in a home where the calendar that featured his uncle was hanging on a wall. “It was just something we were always proud of,” he said.

Linda, his wife, wrote Facebook posts about French that went up on Memorial Day and Veterans Day. One of those caught Wigo’s attention, and soon dots were getting connected across the country.

Wigo wrote a story about French for a swimming magazine in 2020 and then several updates. Other media picked up the story, including the Omaha World-Telegram.

A change.org petition was started, asking the Pentagon to give French the Medal of Honor. A congressman in Nebraska took to the floor of the House in June 2021 and extolled what he called “one of the most under-appreciated sacrifices in American military history.”

Then came the Navy and Marine Corps Medal, awarded posthumously to French’s family. The naming of the Navy pool in San Diego in his honor, and the post office in Omaha.

“It’s such a wonderful coming together of all these threads,” Decker said, “and the main thing we all agree on is this: More people need to hear this story.”

Staff researcher Merrie Monteagudo contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.