The sun was shining again recently when Fidencio Velasquez visited what used to be 90 acres of prime Ventura County strawberry fields.

He pointed to a 40-foot storage container that Santa Clara River floodwaters had swept off a neighboring farm and deposited before him. Overturned tractors and fertilizer bins were strewn about like toys, while the deep channels between crop rows were filled with mud. A harvesting machine was damaged beyond repair. Metal pipes, hoses and trash littered the farm’s outskirts.

“It’s a total loss,” he said.

Velasquez, a supervisor at Santa Clara Farms in Ventura, estimates that the expense of cleaning up and replacing damaged crops, machinery and equipment could run upwardof $900,000. In the meantime, 150 of his employees would be out of work for weeks.

Throughout California, farms that have struggled to cope with years of severe drought have now been dealt additional misery by a series of deadly atmospheric rivers that have devastated operations, even while helping to fill dwindling reservoirs. In many cases, the losses are being felt most sharply by the thousands of farmworkers who have suddenly found themselves unemployed or working fewer hours in dangerous conditions while also dealing with damage to their own homes and vehicles.

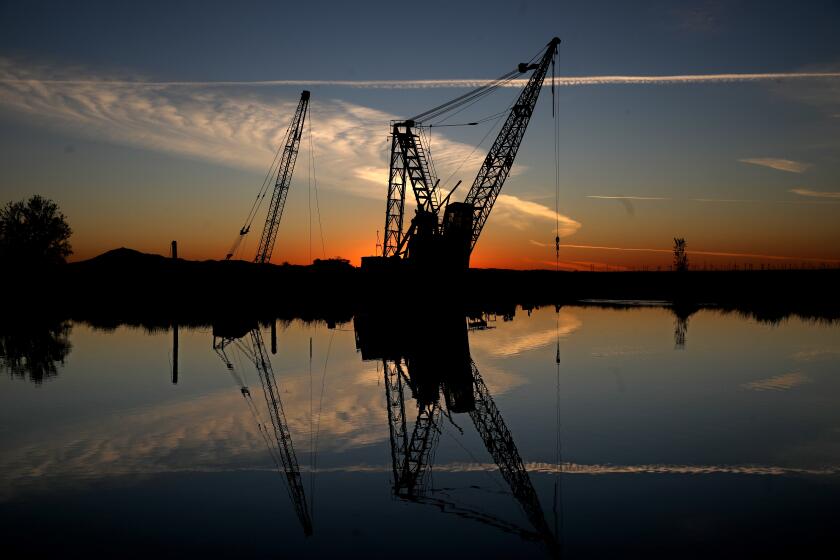

About 95% of the water that flowed into the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta in the first two weeks of January ended up in the Pacific Ocean. Here’s why.

The flooding is just the latest in a continuing series of environmental crises that have affected farmworkers in recent years, including laboring in extreme heat, inhaling harmful wildfire smoke or losing work due to drought. Last year, approximately 12,000 agricultural jobs were lost when California’s irrigated farmland shrank by 752,000 acres, or nearly 10%.

“We have compounding and cascading disasters from extreme storms, flooding, wildfires, heat waves and drought that are all impacting farmworkers,” said Michael Méndez, assistant professor of environmental planning and policy at UC Irvine. “This is just a part of the larger history of disproportionate impacts that this population is experiencing.”

Méndez said farmworkers are especially vulnerable to extreme climate events because they are low-income; most are immigrants without legal status, which makes them ineligible for unemployment benefits and health insurance; and because state and local governments weren’t doing enough to protect a vital workforce.

They “have not provided enough resources, disaster planning, preparedness, translation services for these communities before a disaster happens,” he said. So when disasters do strike, “the experiences are amplified because resources are often not targeted, or they’re withheld from these communities.”

For Ventura farmworkers like Octavio Diaz, January is traditionally a time of year when work on strawberry fields begins to pick up. That is not the case this year.

“It was raining almost every day and you couldn’t work, so we lost hours,” said the 37-year-old. “And there aren’t many places where we can work right now — most of the strawberries were ruined.”

Since December, Diaz and his wife have lost about $3,000 in income from reduced work. Rather than the usual five-day, 35-hour workweeks picking fruit, they’re lucky if they even get one. Their monthly trips to food distributions have increased from once or twice to four or five, he said.

When they do get called to work, fields can be hazardous. Diaz injured his right leg about a month ago trying to pull it out from deep, sticky mud. It still hurts, he said, but he takes what little work is available.

“I kept working after I hurt my leg because we sustain ourselves by working in the farms,” said Diaz, who has six children. “We don’t have other sources of income. You have to work to be able to support your family.”

In Ventura and across California, farmworkers have been contending with flooded homes, damaged cars and reduced or lost work hours since a series of atmospheric river storms pummeled the state. Many have been relying more on food giveaways to offset financial losses, and those who are working are sometimes doing so in flooded or muddy fields.

“Many of the farmworkers are in a Catch-22,” said Antonio De Loera-Brust, communications director for the United Farm Workers union. “You either work in unsafe conditions or you’re losing work.”

In recent weeks, UFW has tweeted videos showing the effects of winter storms across the state. In Madera County, almond orchards were saturated with rain that made them impassable for farmworkers and tractors. In Monterey County, flooded vegetable fields prevented a worker from using a tractor.

Experts say California’s recent series of storms was no more severe than what the state has experienced in the last century.

In Lamont, near Bakersfield, hundreds of farmworkers lined up for a food distribution last week. The union said they served 450 families — 100 more than usual — with many saying they hadn’t worked for weeks because of rain.

In the Central Valley, Norma Roman, 42, worked only three days last week out of the usual five pruning mandarin and almond trees. The week before that, “we didn’t work even one day.”

When they work, she and her husband each make about $110 daily. They put their income toward more than $1,300 in monthly rent, utility bills and internet service for her 11-year-old son, who needs it for schoolwork.

“The impact for me is that I’m not making money for the bills that I have,” Roman said. “You have to pay the rent and no one is going to wait for you. The little that we’ve worked, we’ve had to save as much as we can.”

Rocio Molina, who works in Kern County, said she has found employment only intermittently over the past weeks. On a recent Monday, she arrived to prune grapes at 7 a.m. but was sent home two hours later because it started to rain. The next day she couldn’t work because of a storm’s aftermath. That week, she worked only three full days, she said.

“It’s an impact financially,” said Molina, 48. “If there’s no work, there’s no money for the bills, the rent, food. The money isn’t enough … the most important thing is to pay the rent so we don’t get evicted.”

She considers herself lucky — other farmworkers she knows worked only one day last week because a pistachio field flooded. Molina said she plans on going to UFW food giveaways to help offset the loss of income.

“We haven’t seen an impact like this recently,” Molina said. “It’s been a long time since it’s rained this hard.”

The agriculture industry is still assessing the toll of recent storms and warns that the upcoming farming season could be delayed as a result.

In Monterey County, officials estimate agriculture losses of at least $50 million. Between 25,000 to 35,000 acres of farming land were “seriously impacted” by floods, said county spokesperson Nicholas Pasculli. Crops, equipment, irrigation systems and well pumps were also lost.

Though most farm fields are idle this time of the year, some newly planted crops were flooded, said Norm Groot, executive director of the Monterey County Farm Bureau. Some planting schedules could be delayed due to food testing requirements “to ensure that there are no pathogens in fields after a flood event.” That could be a 30- to 60-day process, which would affect earlier plantings in February.

A traditional growing season in the county requires up to 46,000 farmworkers to tend fields, and an additional 2,500 work in processing facilities.

Back in Ventura County, officials say it could take weeks to calculate agriculture losses.

As of Friday, only 18% of agricultural operations had reported their damages, totaling approximately $8.4 million in crop, livestock and infrastructure loss, and cost of repair and debris removal, said Korinne Bell, Ventura County’s chief deputy agricultural commissioner. Those numbers are expected to be “exponentially higher” in the coming days and weeks.

“Many people have said that they really aren’t able to assess the damage until the waters recede, literally,” Bell said. “Because of the mud, it’s been difficult to even access some of the areas that have been most impacted.”

Storm damage repairs in Los Angeles County could cost $100 million and continue to grow, according to county officials.

The storms took a similar toll in Northern California.

Belinda Hernandez-Arriaga, founder and executive director of the San Mateo County organization Ayudando Latinos a Soñar, said many farmworkers lost cars and other belongings due to flooding. Some have had to stay in hotels after their houses were flooded, and the number of people who arrived at their first food pantry since the storms nearly doubled.

It’s a disaster that comes on the heels of inflation and the pandemic, Hernandez-Arriaga said.

“This has been another big hit that no one was prepared for. Economically, financially, it’s just another wave of injury to what has already been years of accumulated stress,” she said.

A farmworker lost his belongings after his residence flooded. He wound up in the hospital with heart issues soon after, Hernandez-Arriaga said, “because it just provoked a lot of anxiety and stress that he was already feeling.”

“It just brings to light the physical and emotional trauma that these disasters are having when families are low-income and don’t have the foundations to so easily be able to rebuild their lives without support,” she said.

“These are folks that are working so hard and don’t stop and have not stopped. Even during this flood, they’re still trying to figure out how they’re going to box up Brussels sprouts and at the same time, they’re facing their own challenges at home and economically.”

Sandra De León, 39, has been stressed about money since she stopped working in Sonoma County vineyards in December. She pays all the bills as a single mother of three children, so she had to find work cleaning houses to earn some of the $3,000 she lost from not working in the fields.

After years of drought, she knows California needed the rain. But it comes at a cost to the state’s hundreds of thousands of farmworkers like her.

“I don’t have any financial help at home within my family. It’s really frustrating and a huge worry for me because I wonder, ‘There’s no work. How am I going to support my family?’” she said, her voice cracking. “It makes me sad. I’ve worked for this country for so many years. I’ve worked for these vineyard owners for so many years. I don’t imagine they worry as much as us farmworkers if they’ll be able to pay their rent.”

On Monday, she was finally called into work.

“If we’re considered essential workers — because without us, fruits and vegetables don’t make it to homes, into grocery stores — why don’t they figure out how they can help us when disasters like this happen?”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.