Arthur Duncan, who kept virtuoso tap dancing alive on ‘Lawrence Welk Show,’ dies

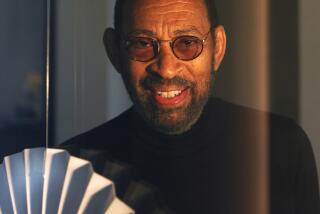

Arthur Duncan, who kept tap dancing visible and relevant across the country on television when most had relegated it to the past and who also broke ground as a Black entertainer, has died at 97.

Duncan was best known for his 18-year run on “The Lawrence Welk Show” as the only Black cast member, and is widely regarded as a trailblazer for a mainstream television variety show. His varied career included appearances on other television shows, in film and in top theater venues around the world.

Duncan died Jan. 4 at a care center near his home in Moreno Valley. It took several days for word of his death — from complications related to a stroke and pneumonia — to get out.

It wasn’t just Duncan’s presence on the Welk show from 1964 to 1982 that mattered, but what he did: virtuoso tap dancing at a time when the art form had become virtually invisible. Tap greats were still around, but jobs had long ago dried up.

Duncan honed his skills as big bands — which often hired tappers — made way for rock bands, and jazz players — who often made their rhythmic inventions alongside hoofers — moved to smaller venues and more experimental musical forms for which tap dancers need not apply. Tap was no longer the dance of the streets, concert halls or Broadway.

“During the 1960s, there were only two shows on television where you could see tap dancing every week: Friday on ‘The Mickey Mouse Club’ for Talent Round-Up Day, and Sundays with Arthur Duncan with a featured dance on ‘The Lawrence Welk Show,’ ” said dance historian Rusty Frank, author of “Tap! The Greatest Tap Dance Stars And Their Stories 1900-1955.” “These were the days before digital recorders, streaming TV and YouTube, so if you wanted to see tap dancing, you had to sit in front of that television at the specific airing time.”

Author and dance critic Brian Seibert wrote that “when Welk introduced Duncan as ‘the young man who is keeping tap dancing alive,’ the epithet was based in fact.”

Having to continually develop new routines, Duncan “generally followed a standard recipe of solid rhythm and big finishes, yet the variety of steps was impressive,” Seibert wrote in “What the Eye Hears,” widely regarded as the most authoritative history of tap.

In one number, Duncan borrowed the idea of dancing atop a piano, something he’d seen performed by the acrobatic Nicholas Brothers and rhythm pioneer John Bubbles. Duncan’s daring edge-to-edge slides clearly made the pianist nervous.

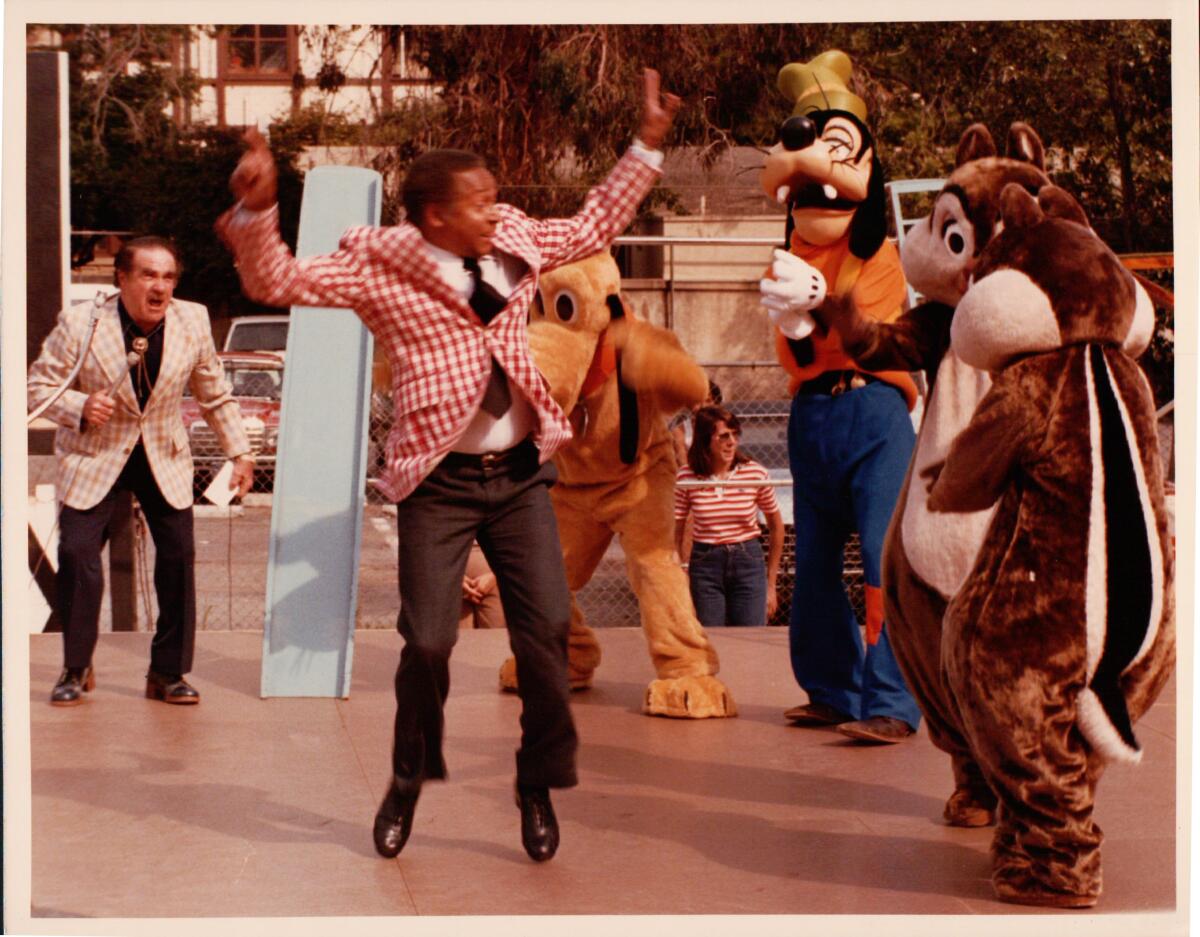

Before the Welk show, Duncan had a semi-regular gig on the comparatively short-lived “The Betty White Show” in 1954. White — who became a lifelong friend and later starred in “The Golden Girls” — pointedly refused demands from Southern affiliates to have Duncan removed from her show.

“There were audience members who were not thrilled to have a Black person on the show,” which also toured around the country, said Ralna English, a dancer and longtime leading singer for the Welk troupe. “I know that. I heard that. Some of these older people were so prejudiced.”

Duncan elected to overlook racial slights.

“He had a lot of pride,” English said. “He always dressed to the nines. Never had a bad word to say about anybody. He stood tall. Always a gentleman.”

Dancer, teacher and entertainer Skip Cunningham used to admire Duncan from afar on the weekly broadcasts.

“He was safe for them and safe for us,” said Cunningham, who also is Black and later became Duncan’s friend. “They couldn’t have picked a better person like that. It wasn’t difficult for him to do.”

Duncan was born on Sept. 25, 1925, in Pasadena, the sixth of 13 children to Corabel LaMar and James Alfred Ernest Duncan, who worked as a merchant seaman before settling in Southern California, according to family members and Duncan himself during an interview in August.

James Duncan later worked for a local oil company, Duncan recalled, and the family became part of a tightknit Black community in the Pasadena area that valued hard work, thrift and education.

“Our parents were very concerned about education and well-being,” Duncan said.

While his siblings pursued other careers — the military, banking, education, firefighting — young Arthur found the arts irresistible, catching the bug when a couple of grade school buddies recruited him to join their would-be dance team.

Soon he was studying formally, getting a discount because his father volunteered to help out at the dance studio. He earned money selling newspapers at a street corner — he’d get extra change by doing a few steps.

He’d use the newspaper gig to get into fine restaurants, where the patrons included performers from the Pasadena Playhouse. Sometimes they’d take an interest in the outgoing, assertive youth who, by the way, was available to dance and sing. A woman who ran a local nightclub gave him a chance.

“I’d come in and do my bit and split. Go home and count the two dollars I had in my pocket,” he recalled.

“You wouldn’t call it dancing,” he said of his early efforts. “I was aggressive and curious and got in the way. So they had to help me to get rid of me. So everything worked out fine, but nothing happened overnight.”

As a youth, Duncan also delivered prescriptions and took some pharmacy classes at Pasadena City College, but his heart wasn’t in it. He also served in the Army — where he spent much of his time performing for troops — receiving his discharge in 1946.

All the while, he hustled dance gigs.

His early supporters included famed choreographer and director Nick Castle, who tried to keep him working, and Henry Mancini, who created musical arrangements for his routines free of charge.

Duncan always went where the work was: “I went to Australia on a 10-day job. I ended up coming home four years later. That’s how it works.”

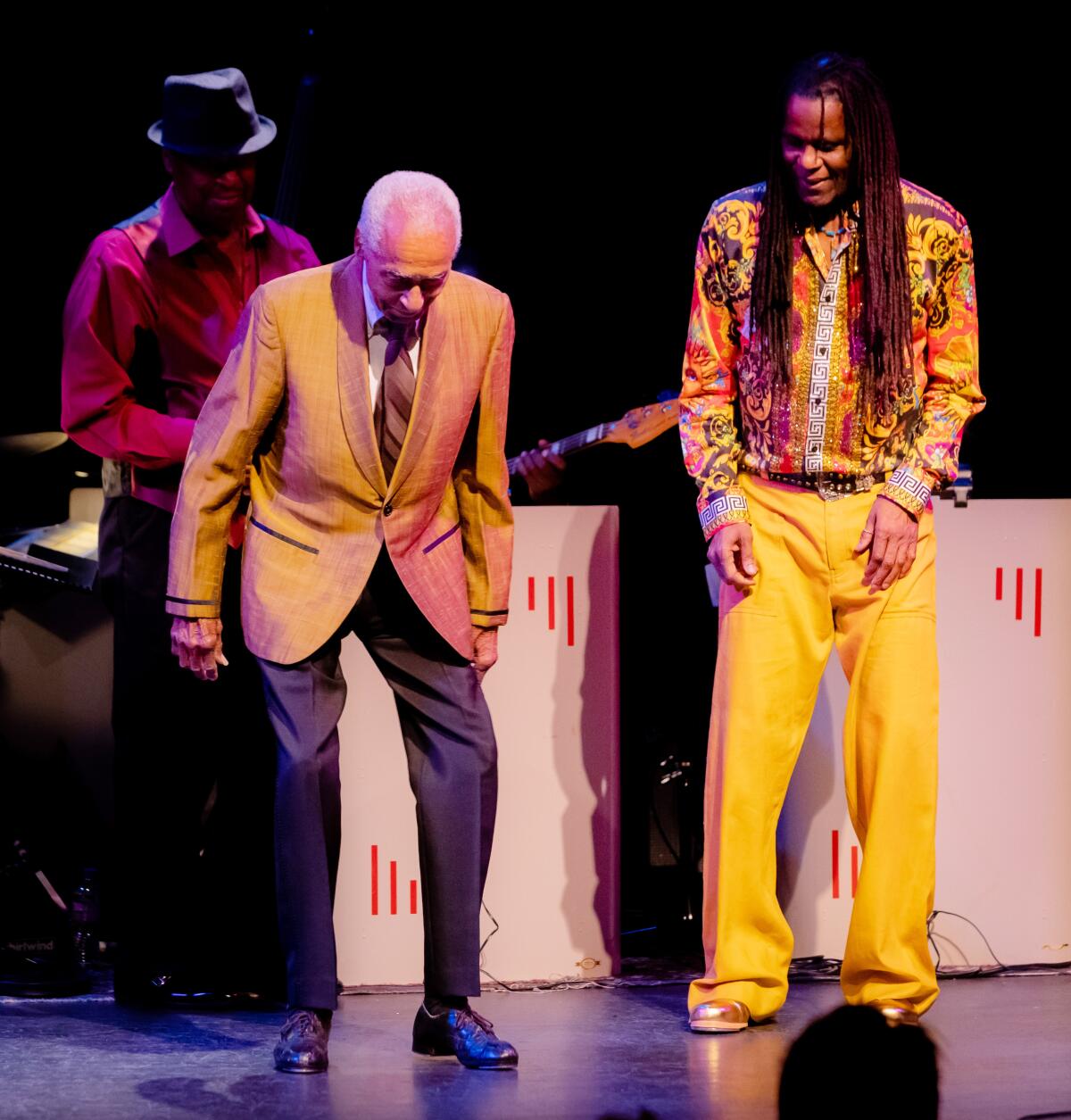

After the Welk show ended, his roles included starring in the Broadway touring company of “My One and Only” with Tommy Tune, said actor Joe Hart, who also had a featured part in that cast.

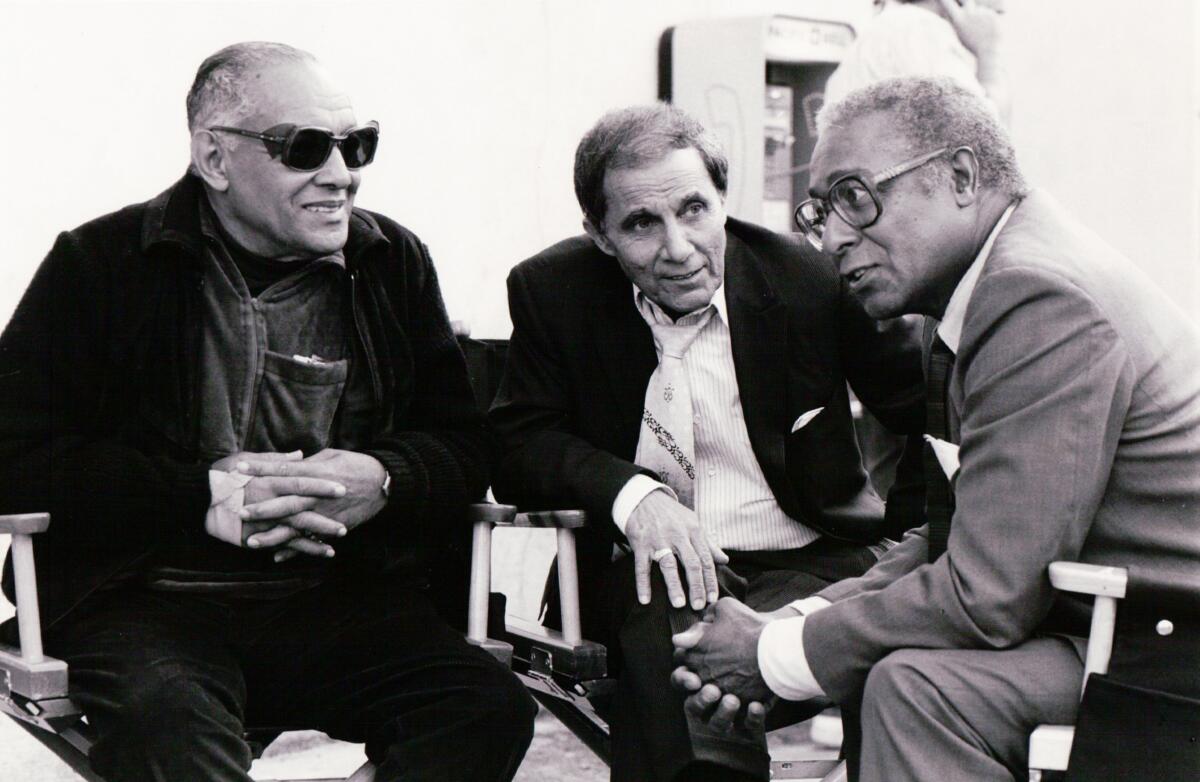

On film, Duncan kicked off the famous challenge scene in the Gregory Hines movie “Tap” (1989), in which the old greats showed their stuff.

Duncan’s TV guest spots included dancing with Dick Van Dyke in the 1992 TV movie “Diagnosis of Murder.”

Along the way, Duncan ultimately became an important bridge to generations of tappers, including through master classes, after it had looked as though serious tap might cease to exist, said respected Chicago-based tapper and teacher Reggio “The Hoofer” McLaughlin.

Duncan disliked talking about how he overcame racism, his personal life and his age. He preferred to marvel at his good fortune, credit all who helped him and emphasize tenacity and hard work. And he always focused on the next gig.

He married twice and had no children. His first marriage, to Donna Pena, ended in divorce in 1973. In 2019, he married his longtime friend and companion Carole Carbone. His survivors include his wife, stepson Sean Carbone and siblings Michael Duncan, Mabel Duncan and Eleanor Starr.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.