California Senate’s new health chair to prioritize mental health and homelessness

State Sen. Susan Talamantes Eggman (D-Stockton), who was instrumental in passing Gov. Gavin Newsom’s signature mental health care legislation last year, has been appointed to lead the Senate’s influential health committee — a change that promises a more urgent focus on expanding mental health services and moving homeless people into housing and treatment.

Eggman, a licensed social worker, co-authored the novel law that allows families, clinicians, first responders and others to petition a judge to mandate government-funded treatment and services for people whose lives have been derailed by untreated psychotic disorders and substance use.

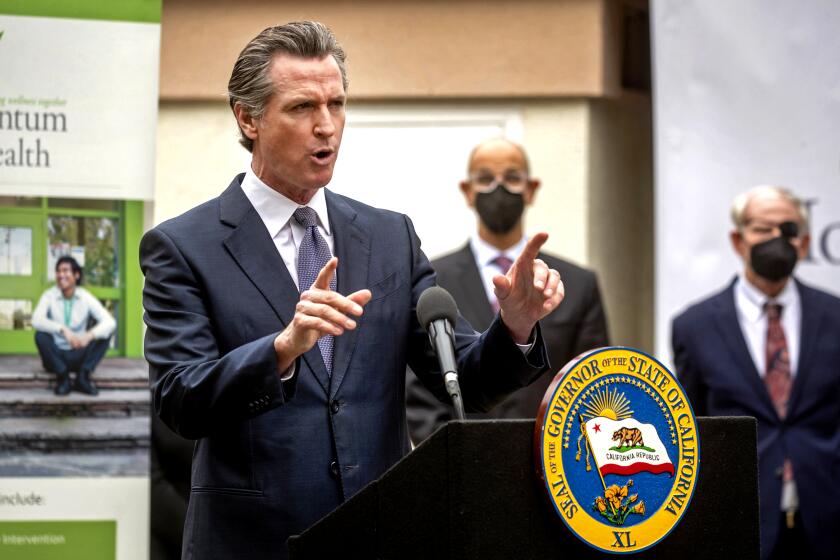

It was a win for Newsom, who proposed the Community Assistance, Recovery and Empowerment Act, or CARE Court, as a potent new tool to address the tens of thousands of people in California living homeless or at risk of incarceration because of untreated mental illness and addiction.

The measure faced staunch opposition from disability and civil liberties groups worried about stripping people’s right to make decisions for themselves.

“We see real examples of people dying every single day, and they’re dying with their rights on,” Eggman said in an interview with Kaiser Health News before the appointment. “I think we need to step back a little bit and look at the larger public health issue. It’s a danger for everybody to be living around needles or have people burrowing under freeways.”

Senate Pro Tem Toni Atkins (D-San Diego) announced Eggman’s appointment Thursday evening. Eggman replaces Dr. Richard Pan (D-Sacramento), who was termed out last year after serving five years as chair. Pan, a pediatrician, had prioritized the state’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic and championed legislation that tightened the state’s childhood vaccination laws. Those moves made him a hero among public health advocates, even as he faced taunts and physical threats from opponents.

The leadership change is expected to coincide with a Democratic health agenda focused on two of the state’s thorniest and most intractable issues: homelessness and mental illness. According to federal data, California accounts for 30% of the nation’s homeless population, while making up 12% of the U.S. population. A recent Stanford study estimated that in 2020 about 25% of homeless adults in Los Angeles County had a severe mental illness such as schizophrenia and 27% had a long-term substance use disorder.

Eggman will work with Assembly member Jim Wood (D-Santa Rosa), who is returning as chair of the Assembly Health Committee. Though the chairs may set different priorities, they need to cooperate to get bills to the governor’s desk.

The CARE Act — like other attempts to legislate treatment for severe mental illness in California — is constrained by the Lanterman-Petris-Short Act.

Eggman takes the helm as California grapples with a projected $24-billion budget deficit, which could force reductions in healthcare spending. The tighter financial outlook is causing politicians to shift from big “moonshot” ideas such as universal healthcare coverage to showing voters progress on the state’s homelessness crisis, said David McCuan, chair of the political science department at Sonoma State University. Seven in 10 likely voters cite homelessness as a big problem, according to a recent statewide survey by the Public Policy Institute of California.

Eggman, 61, served eight years in the state Assembly before her election to the Senate in 2020. In 2015, she authored California’s End of Life Option Act, which allowed terminally ill patients who meet specified conditions to get aid-in-dying drugs from their doctor. Her past work on mental health included changing eligibility rules for outpatient treatment or conservatorships, and trying to make it easier for community clinics to bill the government for mental health services.

She hasn’t announced her future plans, but she has around $70,000 in a campaign account for lieutenant governor, as well as $175,000 in a ballot measure committee to “repair California’s mental health system.”

Eggman said the CARE Court initiative seeks to strike a balance between civil rights and public health. She said she believes people should be in the least restrictive environment necessary for care, but that when someone is a danger to themselves or the community there needs to be an option to hold them against their will. A Berkeley Institute of Governmental Studies poll released in October found 76% of registered voters had a positive view of the law.

Sen. Tom Umberg (D-Orange), who co-authored the bill with Eggman, credited her expertise in behavioral health and dedication to explaining the mechanics of the plan to fellow lawmakers. “I think she really helped to put a face on it,” Umberg said.

But it will be hard to show quick results. The measure will unroll in phases, with the first seven counties — Glenn, Orange, Riverside, San Diego, San Francisco, Stanislaus and Tuolumne — set to launch their efforts in October. The remaining 51 counties are set to launch in 2024.

County governments remain concerned about a steady and sufficient flow of funding to cover the costs of treatment and housing inherent in the plan.

California has allocated $57 million in seed money for counties to set up local CARE Courts, but the state hasn’t specified how much money will flow to counties to keep them running, said Jacqueline Wong-Hernandez, deputy executive director of legislative affairs at the California State Assn. of Counties.

Robin Kennedy is a professor emerita of social work at Sacramento State, where Eggman taught social work before being elected to the Assembly. Kennedy described Eggman as someone guided by data, a listener attuned to the needs of caregivers and a leader willing to do difficult things. The two have known each other since Eggman began teaching in 2002.

“Most of us, when we become faculty members, we just want to do our research and teach,” Kennedy said. “Susan had only been there for two or three years, and she was taking on leadership roles.”

The life of a 31-year-old living with schizophrenia illustrates the toll of illness and the challenge of getting severely mentally ill people off the streets.

She said that Eggman’s vision of mental health as a community issue, rather than just an individual concern, is controversial, but that she is willing to take on hard conversations and listen to all sides. Plus, Kennedy added, “she’s not just going to do what Newsom tells her to do.”

Eggman and Wood are expected to provide oversight of CalAIM, the Newsom administration’s sweeping overhaul of Medi-Cal, California’s Medicaid program for low-income residents. The effort is a multibillion-dollar experiment that aims to improve patient health by funneling money into social programs and keeping patients out of costly institutions such as emergency departments, jails, nursing homes and mental health crisis centers.

Wood said he believes there are opportunities to improve the CalAIM initiative and to monitor consolidation in the healthcare industry, which he says drives up costs.

Eggman said she’s also concerned about workforce shortages in the healthcare industry and would be willing to revisit a conversation about a higher minimum wage for hospital workers after last year’s negotiations between the industry and labor failed.

But with only two years left before she is termed out, Eggman said, her lens will be tightly framed around her area of expertise: improving behavioral healthcare across California.

“In my last few years,” she said, “I want to focus on where my experience is.”

This article was produced by KHN (Kaiser Health News), one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation).

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.