Dispute arises over P-22’s remains as Indigenous people fight for Griffith Park burial

Even in death, the mountain lion known as P-22 is caught between two worlds.

To many Angelenos, he was a celebrity and symbol of an untamed California that’s quickly vanishing. But for centuries, Native American tribes called mountain lions teachers and viewed them as their relatives.

Now that P-22 has been euthanized by wildlife authorities, it’s unclear what will happen to the remains of the famous mountain lion. While government agencies and museum officials consider the final resting place for the cat, the Native American community in Southern California wants P-22 to be buried near Griffith Park with a ceremony that honors his spirit.

Originally from the Santa Monica Mountains, P-22 gained worldwide recognition after he was photographed in front of the Hollywood sign and lived in Griffith Park on ancestral Gabrieleno/Tongva land.

P-22, who has been euthanized due to severe injuries, was thought to be about 12 years old.

The Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County received P-22’s body from the California Department of Fish and Wildlife on Friday. Although previously considered, museum officials said Thursday they do not plan to taxidermy P-22’s body or put his remains on display, which was a major concern for the Native American community.

But it’s still unclear what the future holds for the big cat.

Researchers were already in the process of collecting samples and performing a necropsy — a type of an animal autopsy — on P-22 when they learned about the concerns from the Native American communities. That process has been put on hold while the museum gathers more feedback from those groups. Several Native American people contacted by The Times said they had not initially been approached by the museum for feedback but have since been in talks about how to honor P-22’s remains.

Research on P-22’s body could show the firsthand effects of an urban setting on a mountain lion who managed to eke out his existence for more than a decade surrounded by humans, according to biologists. It’s not likely that there will be another like P-22, so he would yield unique information about his experience, conservationists say.

But the thought of P-22 going to a museum as a specimen fills tribal community members with dread.

State officials ultimately decided to euthanize P-22 at 9 a.m. Saturday morning due to serious health issues.

“That’s not our way. That’s a scientific colonial way,” said Kimberly Morales Johnson, tribal secretary of the Gabrieleno/Tongva San Gabriel Band of Mission Indians. “That cat is a relative to us.”

The Tongva word for mountain lion is tukuurot. In their creation story, mountain lions were one of several animals that watched early humans grow and flourish.

Alan Salazar, tribal elder with the Fernandeño Tataviam Band of Mission Indians, whose ancestral land includes part of the Santa Monica Mountains, understands the importance of studying P-22’s body.

But there’s a storied history with universities and museums that collected Native American cultural items and human remains, Salazar said.

“Almost every university in California has boxes of Native American human remains. Bones, skeletons, skulls that they claim they need to study to learn more,” Salazar said. “And our answer is always the same: ‘How long do you need?’”

Natural History Museum representatives said in a written statement that they “recognize and honor that people are impacted in different ways” by P-22’s life and death and do not plan to display P-22’s body at the museum.

“This has been a particularly emotional and difficult time for our team members who have devoted the last decade to understanding and learning from P-22,” the statement said.

The museum said it is in conversations with Chumash and Tongva tribes to give respectful consideration to what happens to his remains.

A California Department of Fish and Wildlife spokesperson said the agency did not consult with the tribal community before it decided that the Natural History Museum would receive P-22’s remains. Fish and Wildlife officials were “laser focused” on P-22’s health once they found him in a Los Feliz backyard on Dec. 12 after he was hit by a car.

“It took all of our energy and effort to work through those decisions,” Fish and Wildlife spokesperson Jordan Traverso said in a written statement. “I acknowledge and accept we may have overlooked this important step.”

P-22’s remains were being held at the San Diego Zoo, where he was brought for treatment before officials made the decision to euthanize him Dec. 17.

Whatever comes from the discussions about what to do with P-22, Fish and Wildlife believes his story will be able to teach future generations about his struggles as part of a segregated wildlife population.

State and county agencies often consult with members of tribal communities when new developments are built on their ancestral land.

Members of the Gabrieleño Band of Mission Indians, Kizh Nation, have been asked to provide feedback for state projects built on their ancestral land numerous times, Indigenous biologist Matt Teutimez said. The process can include a blessing performed by tribal elders, and in other instances tribal members provide cultural and scientific feedback.

Native American input can often feel like an afterthought, Teutimez said.

“They usually just want our participation. They already have their minds made up with their Western thought of how to remedy the problem,” Teutimez said. “All they wanted was our tribe to get involved for the photo op.”

He’s hopeful that P-22 can provide a teachable moment on how Western culture needs to reevaluate its relationship with wildlife and consider it more than just animals.

Tongva artists pay tribute to P-22, the celebrity mountain lion that was euthanized Saturday, with a song and a poem.

P-22 has already left an indelible mark on the world and done more to push conservation efforts than any other animal in recent years, conservationists and researchers said.

His perilous trek across two major freeways more than a decade ago showed that mountain lions face destruction due to habitat loss and lack of biodiversity. P-22 inspired conservationists to push for an $88-million wildlife crossing over the 101 Freeway near Agoura Hills, so other mountain lions and wildlife would not be blocked in by human development.

Beth Pratt, a regional executive director in California for the National Wildlife Federation, considers herself one of P-22’s biggest boosters. His death has lingered with her for days, and she has trouble imagining a Griffith Park without him. While she understands the importance of studying P-22’s life, Pratt stands with the Native American community in its call to bury the big cat in Griffith Park.

“I hope discussions and some sort of compromise can be made that allows some of what the museum needs for scientific purposes, but ultimately also allow for a respectful burial,” Pratt said.

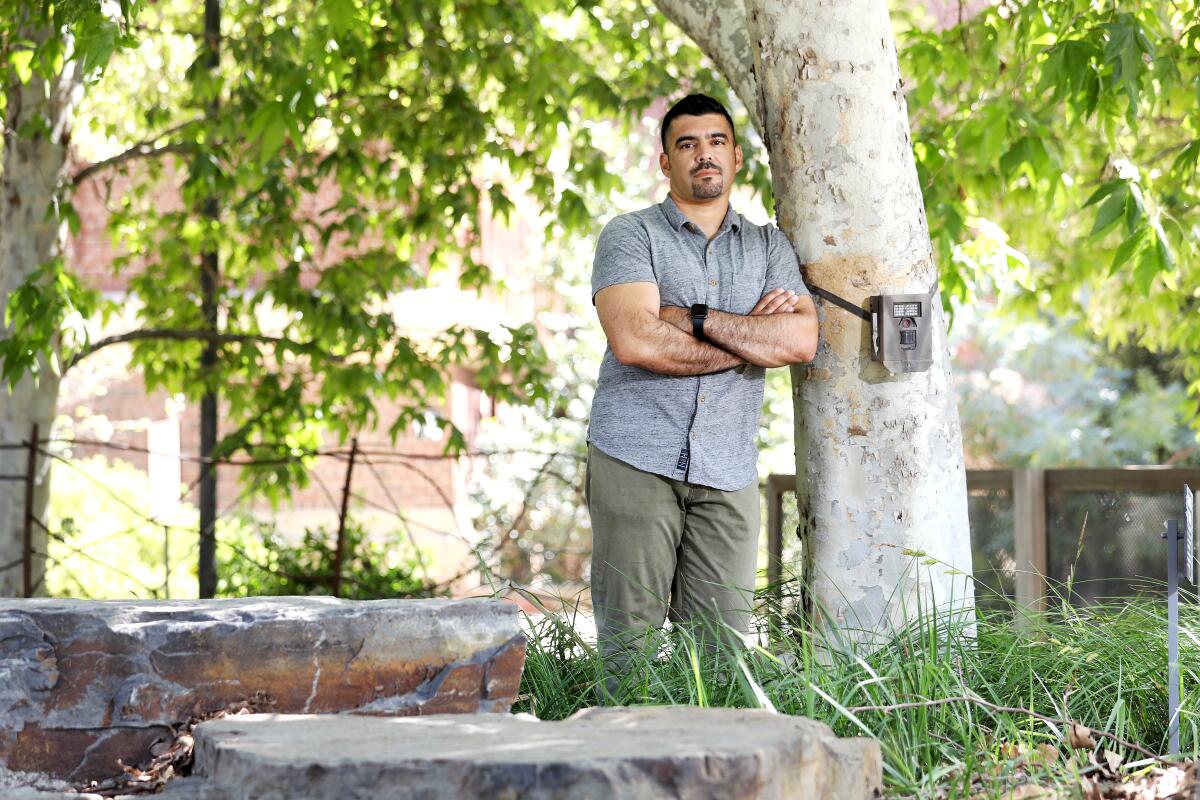

More than a decade ago, a mountain lion roaming Griffith Park seemed like an urban legend to biologist Miguel Ordeñana, who grew up around the park. In 2012, he was the first person to photograph P-22 i with a motion-sensor trail camera. At the time, P-22 was an unnamed cat that proved the impossible and found his way to the park.

Ordeñana, now the wildlife biologist with the Natural History Museum, is trying to clarify the museum’s intentions for P-22.

More than a year ago, he applied for the Natural History Museum to receive P-22’s remains from the state for research purposes. He called it a painful decision, because he always hoped P-22 would die peacefully in Griffith Park. He previously thought that P-22 would be put on display at the museum, but now he hopes there can be a dialogue about what to do.

Ordeñana said he applied for P-22’s remains “intentionally so that it could be accessible to the Indigenous community. But I could have done better. I appreciate being able to learn from that.”

Like so many in the scientific community who watched the big cat grow old, Ordeñana is still processing P-22’s death. In many ways, Ordeñana is having a hard time with the death, for a creature who was more than an animal and one he speaks of with great reverence.

“We’re not sure exactly what the next steps are,” Ordeñana said. “I think we all want what’s best for P-22.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.