MORROW COVE, Calif. — The outrage and frustration had been building for years at California State University’s Maritime Academy, an elite training ground for students bound for work on the sea. It reached a peak last year, when student cadets publicly confronted the school’s president, a retired rear admiral.

Dozens of cadets gathered on the quad that day to protest what they said was widespread sexual misconduct, racism and hostility toward women and transgender and nonbinary students.

One student told President Thomas Cropper that a male classmate sexually harassed her. Another accused administrators of failing to adequately discipline cadets who exchanged messages disparaging trans people as “fags” and comparing them to a castrated dog.

The reckoning in November 2021 exposed what students have long discussed among themselves at the school, one of seven maritime academies in the United States and the only one of its kind on the West Coast.

Long-standing claims of sexual harassment and misconduct, homophobia, transphobia and racism on campus and during training cruises have roiled Cal Maritime and triggered an atmosphere of dread for many students, a Times investigation has found.

One woman told The Times she was raped by a male classmate and dropped out earlier this year to avoid facing her alleged attacker while a campus investigation has dragged on for months.

A cadet discovered their motorcycle tires slashed and the word “dike” carved into the gas tank. Another student said she now carries a knife for protection after a cadet tried to coerce her into having sex.

Females expressed an understanding that it is not a matter of ‘if’ they will experience sexual harassment or assault,” the report concluded, “but ‘when’ and ‘how often.’”

— Campus report

And a university official who sent out a campus email demanding that the school do more to combat hate and racism found herself the subject of discipline — for unauthorized use of school email.

The accusations at the 800-student campus on San Francisco Bay are yet another crisis for the California State University system, which has been rocked by allegations of sexual misconduct and retaliation, sparking calls for reforms and leading to the resignation of top executives.

Times investigations earlier this year found breakdowns and inconsistencies in the way that campuses in the nation’s largest public four-year university system handle sexual misconduct and retaliation claims.

Recent revelations about how California State University handled sexual harassment and workplace retaliation complaints have rocked the nation’s largest four-year public university system.

Until now, Cal Maritime, the smallest and most insular of the CSU campuses, has escaped the public scrutiny that has roiled other schools in the system. One reason is that the school prepares cadets, as they are called, for careers in the maritime industry, and some fear formally reporting misconduct will damage their future job prospects, according to students, faculty and alumni.

Cropper did not respond to requests to be interviewed for this report. Two weeks after Times reporters visited his campus office this fall to seek an interview, he announced that he would step down in August. He said he made the decision in the summer.

Cal Maritime said in statements that top administrators have “strongly and repeatedly denounced” misconduct and contend that they have taken a variety of actions to combat the problems. They said the school improved the complaint reporting process by hiring two consultants, increased campuswide training on sexual harassment and how to report misconduct, hired a full-time advocate for victims, hosted campus forums and opened a community center that serves as a “welcoming place for cadets to gather and study.”

Other university promises have gone unfulfilled.

After the gathering on the quad, Cropper and his senior administrators said they would hire a full-time coordinator and three deputies to oversee misconduct investigations at the academy, which has long been a leader in preparing students for good-paying jobs in the maritime industry.

A year later, the school has yet to hire the coordinator, citing “failed searches,” and is still looking for someone to fill that role. But it now says it will no longer hire the deputies. Instead, officials said in statements that the campus will rely on about half a dozen employees as “liaisons” who will respond to initial reports and concerns regarding sexual harassment, discrimination and misconduct. They will take on the work in addition to their regular duties and begin training in January, the campus said.

A review of hundreds of records reveal inconsistencies in addressing sexual harassment allegations at California State University.

The scale of the challenge was captured in two reports completed this year by outside experts in sexual misconduct and student rights. One report focused on campus issues and was ordered by the faculty senate in response to longstanding concerns. The other examined training cruise culture and was requested by the administration following reported misconduct.

The training cruise report referenced unspecified sexual misconduct on the Training Ship Golden Bear last year and said cadets reported frequent use of the N-word and “rampant use” of the words “faggot,” “homo” and “dyke,” to refer to fellow cadets, including those in the LGBTQIA+ community.

The other report found that cadets were reluctant to make formal complaints about misconduct out of fear of retaliation, becoming the subject of gossip by classmates and causing damage to their own careers. Multiple people interviewed by the experts said they lacked faith in the ability of the school’s administration to make the necessary changes, according to the report.

“Females expressed an understanding that it is not a matter of ‘if’ they will experience sexual harassment or assault,” the report concluded, “but ‘when’ and ‘how often.’”

::

Nestled between a tree-lined waterfront and brush-covered hillside, the Maritime campus in Vallejo offers sweeping views of the northern San Francisco Bay. Cadets can study on benches and lawn chairs along Morrow Cove overlooking ships that glide past the Carquinez Bridge, a hulking steel structure that spans a narrow tidal strait.

From a boathouse and docks, the school operates more than a dozen vessels, including the Golden Bear, where cadets participate in summer training cruises that last up to 60 days. The campus also features a state-of-the-art simulation center with 360-degree projection systems that create real-time exercises such as working on the bridge of a ship as it navigates across the bay or dealing with oil spills.

Founded in 1929, Cal Maritime was the first academy of its kind to admit women in 1973 and joined the California State University system in 1995.

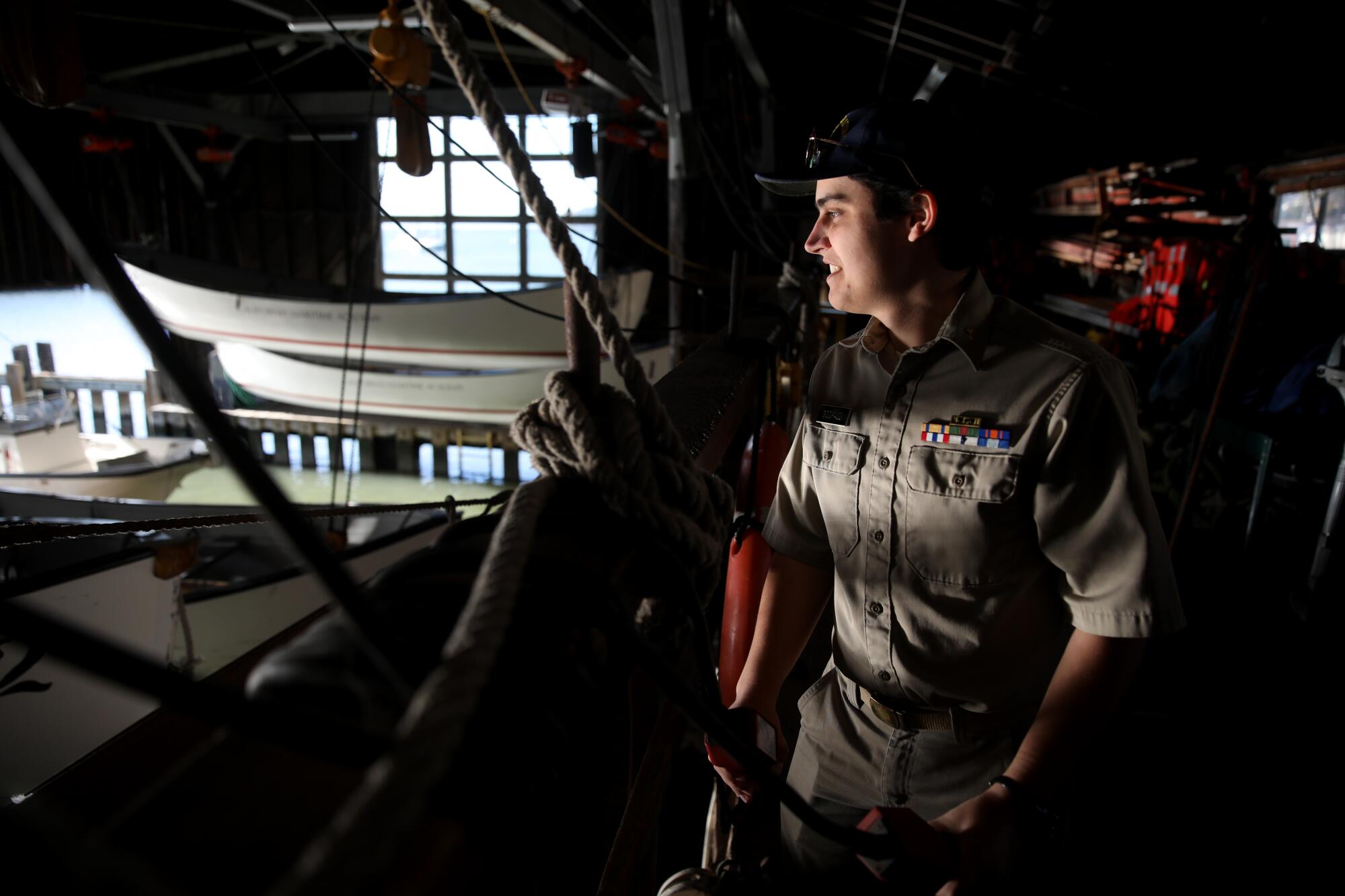

Cadets can pursue majors offered at other CSU campuses, such as business administration and mechanical engineering, but many are taking special training to earn U.S. Coast Guard licenses for positions such as third mate on the bridge of a ship and third assistant engineer in the engine room. Students laud the training but say the specialized courses make it difficult to transfer to other schools in the system.

Students, faculty and experts say the university’s statements on the allegations have undermined public confidence in the school.

Three times a week at 7:20 a.m., flags are hoisted up poles resembling the mast of a ship, and cadets typically stand at attention in khakis for uniform and grooming inspection. Formation on the quad is a mainstay of the Corps of Cadets, which all students are required to join.

The corps is led by cadets who serve as officers and hold authority over junior students. Corps officers conduct inspections as well as assign duties such as standing watch on the deck of the Golden Bear. They report to several commandants, staff positions typically filled by military veterans.

Cal Maritime officials point out that they are the most diverse of all the nation’s maritime academies. But in comparison with the CSU overall — where nearly 60% of the students are women and a little more than 20% are white — the school is one of the least diverse of the 23 campuses. Of the cadets at Cal Maritime, 80% are men and 48% are white.

::

Allegations of mistreatment of female cadets on the campus date back decades.

One alumna told The Times that a cadet drugged and assaulted her 11 years ago when she was a student. She did not file a complaint, saying she didn’t understand the reporting process and stayed at the academy only because her attacker left.

“It’s soul-sucking to know how long these problems have been there,” said the woman, who asked not to be identified. “This has been an issue for decades.”

The review comes amid an ongoing Times investigation into breakdowns in CSU’s handling of reports of sexual misconduct, workplace bullying and retaliation.

One of the outside investigative reports released this year detailed misconduct on two training cruises on the Golden Bear in summer 2021. The misdeeds “did not happen in a vacuum,” the report said, and cited a “more systemic problem that should be carefully assessed.”

Cadets, alumni and faculty who spoke to The Times echoed the accusations contained in the report, pointing out the unique challenges posed by working in close quarters on sea duty, which is required for those seeking a Coast Guard license.

The 500-foot Golden Bear is the pride of Cal Maritime, and the summer cruise, during which cadets train as merchant marines at the direction of a captain, entices many to enroll at the school. For months at a time, roughly 300 cadets live and work together on the navy and gold ship, learning to navigate open waters along routes that include the Pacific Coast to Hawaii and through the Panama Canal to Europe.

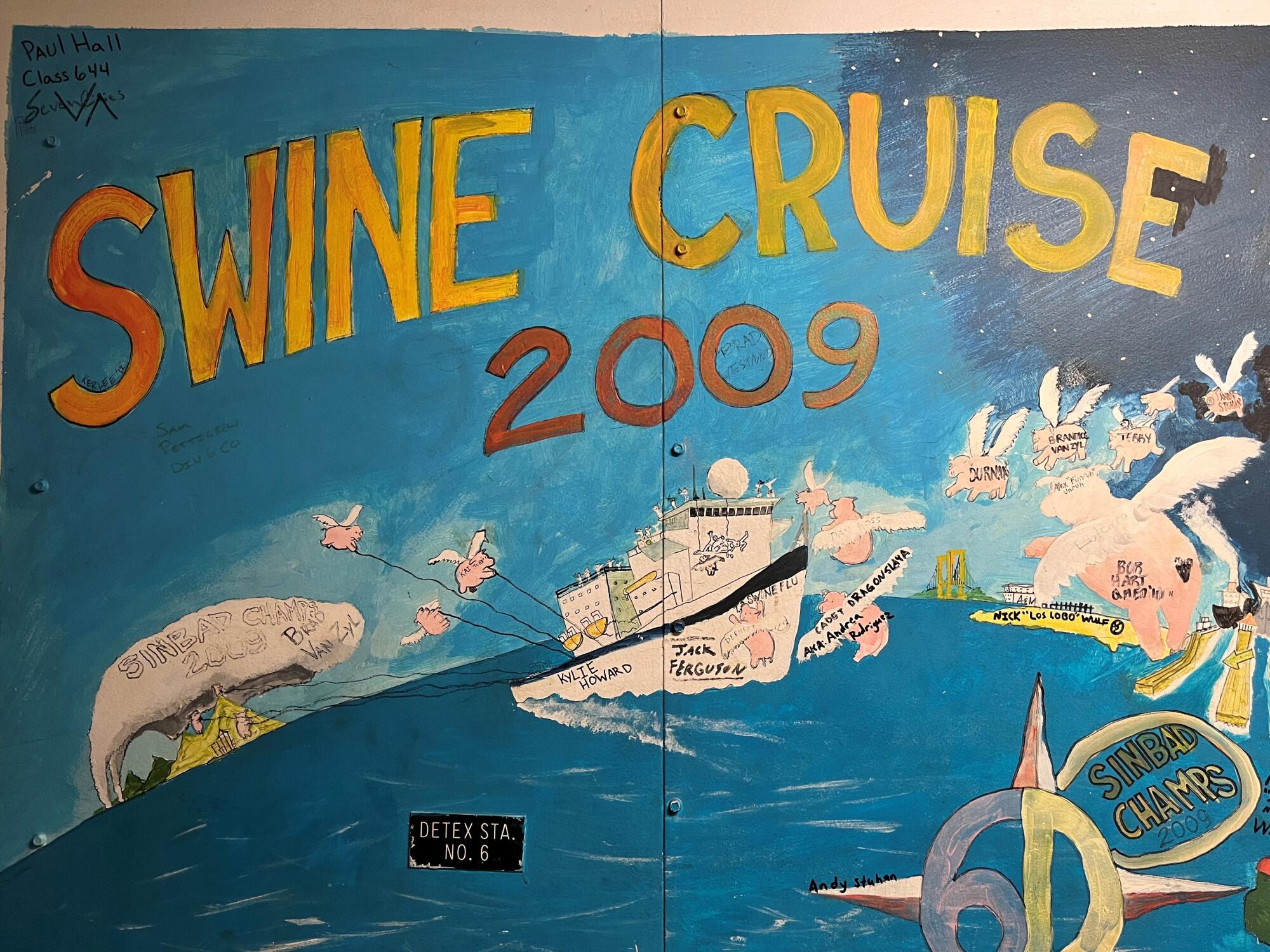

The experience creates close bonds among cadets. They leave behind colorful murals below deck that encapsulate the camaraderie — ships and beaches; a sunbathing gorilla; a mermaid perched atop an anchor. Older paintings of scantily clad women have been painted over.

But the narrow passageways and tight living spaces also mean that cadets have little escape from unwanted attention — or one another. Beds are stacked, and rooms can be accessed by connecting bathrooms. The line for the mess area wraps down the hallway past the office of the commandant, making it difficult for a cadet seeking help to do so unobserved.

Students and alumni said cadets who report misconduct worry that they will be ordered to leave at the next port to avoid continued contact with one another, forcing cadets to wait another summer to fulfill their required sea training.

The decision by President Judy Sakaki comes after a Times investigation detailed allegations of sexual harassment against her husband and retaliation by her.

In a statement, the school said it launched reforms after the training cruise report to ensure a “positive, safe and equitable” experience, including improving protocols for reporting misconduct, designating a liaison to handle reports and requiring mandatory training on sexual assault and harassment.

But records of an investigation aboard a training cruise reviewed by The Times show that complaints of wrongdoing continued.

In May, for example, the Golden Bear captain concluded that a preponderance of evidence showed that a cadet had made threatening and disparaging comments, creating a hostile work environment for LGBTQ students, the records said.

“It’s gotten worse,” said chemistry professor Frank Yip, a longtime advocate for cadet safety. “The students here feel unheard.”

::

Deep in the bowels of the Golden Bear, Tassha Tilakamonkul was working on a pipe system as part of her cadet training.

Tilakamonkul, 18, who dreams of voyaging on oil tankers as a third assistant engineer, said that a male cadet was telling her crude jokes and boasting about his sexual exploits on the ship.

She said he followed her to the deck and down a gangway to a grassy area near the quad, where he grabbed her and pulled her close, telling her that he and his girlfriend were seeking another partner.

“He had essentially tried to coerce me into having sex,” said Tilakamonkul, noting that she was 17 at the time. The cadet held her close as she repeatedly tried to break away, only to be pulled back, she said. The male cadet is no longer on campus.

Tilakamonkul, who serves as president of the Gay/Straight Alliance Club, recounted her story on a recent afternoon in a laboratory building overlooking the bay.

Lawmakers cited Times investigations uncovering inconsistencies in how harassment and retaliation claims are investigated across California State University.

She recalled facing Cropper on the quad, telling him that “I was assaulted at this school.” Cropper, who has been president of the campus for a decade, stood silent and just nodded, according to Tilakamonkul.

She said he “never followed back up, never said anything, which is terrible.”

Campus officials said in a statement that they were “not aware of an instance where a cadet raised an issue but received no follow-up.”

Tilakamonkul said she saw no use filing a report with campus officials who investigate misconduct under federal Title IX law, which prohibits discrimination and harassment based on sex, race or gender.

Classmates who’ve dealt with Title IX officials recounted being asked about their clothing and whether they were drinking alcohol, all of which made them feel like they were not believed, according to Tilakamonkul.

She said cadets use knives for work on the training vessels but added that she carries one primarily for protection from other cadets, saying “it’s kind of become part of my body.”

She now offers this advice to other women on campus: “Always have a knife with you.”

::

Months after one young woman said she was raped by a classmate, she fled from Cal Maritime. On campus with her alleged attacker, she was consumed by anxiety. She believed her only option was to leave the university.

She described being in class only a few feet from her alleged attacker as “the most gut-wrenching thing in the world.”

She said it took time to process what had happened to her last year: She alleged a man she once trusted and considered a friend pushed her onto a bed, pinned her by the neck and assaulted her while they were off campus.

The woman, who spoke on the condition that she not be identified, said she filed a complaint with Cal Maritime officials early this year alleging she was raped by a cadet. The investigation has not concluded. She declined to name her alleged attacker.

She previously shared her story with trusted cadets and faculty, several of whom spoke with Times reporters. The Times does not typically identify victims of sexual assault.

The campus declined to discuss specific cases, but said it offers students “supportive measures” such as counseling, ordering cadets not to contact one another and moving students to different classes “when feasible.”

The woman said she was in the same class as her alleged assailant but was unable to change her schedule. She felt powerless and began hyperventilating between classes.

She now spends her time scrubbing the decks of tugboats and working at a bar near her home. She still dreams of a career in the seafaring industry but has no plans to return to Cal Maritime.

::

Last fall, after a U.S. Merchant Marine Academy student accused an engineer of rape, calls for reform reverberated across the male-dominated profession and onto the campus of Cal Maritime.

Cadet Sophie Scopazzi, 25, who wants to be a third mate on a deep-sea ship, pressed the school to eliminate gender-based policies regarding hair length, earring-wear and nail polish. Nonbinary and transgender cadets like Scopazzi were required to out themselves to receive permission to change their appearance, which they contend is an invasion of privacy.

The campus said that earlier this year it updated its uniform and grooming policies to be more gender-neutral. Its revised uniform policies do not state that cadets are required to say whether they are nonbinary or transgender.

Scopazzi’s calls for change prompted a disturbing backlash from some cadets, including corps leaders who disparaged LGBTQ classmates in comments sent to one another via text and email.

In a group text chat in November 2021, cadet leaders mocked LGBTQ classmates, saying they needed to “harden the f— up” and calling them “fags.” Others said that the U.S. should “send tranny soldiers back to Afghanistan” and disparaged people who had surgeries to “snip” their genitals.

“I can’t go anywhere else ... This is what I want to do in life.”

— Cadet Sophie Scopazzi

The messages reviewed by The Times did not identify the high-ranking cadets involved. But in an email to classmates announcing his resignation, the student who commanded the corps admitted he took part in the exchange, saying his conduct “sent the wrong signal in my role as a leader and broke your trust.”

In a separate letter shared among cadets around the same time, one student said it was “sad that people these days are questioning themselves about who and what they are. As an example, a male castrated dog does not suddenly become a female dog because his reproductive organs were removed.”

An investigation by Cal State San Marcos authorities concluded two professors had engaged in egregious sexual harassment and misconduct in violation of university policy.

The cadet also questioned why someone would attend Cal Maritime if they didn’t support the policies.

“I can’t go anywhere else ... This is what I want to do in life,” said Scopazzi, who has created a website for the Cal Maritime community to speak out about their experiences. It includes anonymous posts from people who identify themselves as cadets and alumni and discuss being raped and sexually assaulted while attending the academy.

Within hours of the campus learning of the group texts, the head commandant messaged the campus community denouncing the actions as “misconduct” and suspended the cadet leaders from their positions, according to an email reviewed by The Times. The campus launched a student conduct investigation, officials said in a statement.

In a campus message, Cropper called the language “offensive, spiteful and highly disappointing” but he also said it was “Constitutionally protected free speech which I will defend for everyone at our academy.”

In interviews with Times reporters, cadets, staff and faculty questioned why Cropper didn’t declare zero tolerance for hate speech.

Scopazzi said the text messages did not name anyone but were clearly directed at her and the two other trans cadets who had come out at the academy. She said she no longer felt safe and moved off-campus. She filed a Title IX report over the messages and was told by the Maritime Title IX officer that the chat, “though hateful,” did not directly name her and was protected 1st Amendment speech.

After her case was dismissed this year, she appealed to the Chancellor’s Office in Long Beach, which upheld the campus decision.

“We’ve got all these people who should be doing a better job here,” Scopazzi said of top leaders. “They’re the ones who are supposed to be taking care of us.”

::

Around the same time that cadets confronted Cropper on the quad last year, the women’s basketball team met with him after players were targeted with anonymous racist and homophobic social media posts. One player told the president that she had been sexually assaulted and feared facing her assailant on campus, according to two women who attended the meeting.

The women, who asked not to be named for fear of retaliation, recalled Cropper saying that it would be cowardly for the player not to go to classes.

“We felt gaslit,” one of them said. “It sucks that this is the expectation we have for our school, like nothing is ever going to get resolved.”

In a statement, the campus said that Cropper told the team that the “people behind these messages were exhibiting abhorrent behavior and were, indeed, behaving cowardly.”

Cadet Huck Parra recounted telling Cropper at the quad that if he didn’t take more aggressive action against hate speech, the situation “was going to escalate and it was going to get worse.”

Several weeks later, Parra’s motorcycle tires were slashed and “dike” was carved in the custom wrap of the gas tank.

“Would love to put a lynch around your neck.”

— A Black cadet received anonymous text messages filled with racist, sexist comments

Campus police obtained a conversation surreptitiously recorded by a cadet on his phone inside a dorm room, where a freshman identified by police as a “lead suspect” was heard saying he was responsible for the crime, according to police records reviewed by The Times.

The suspect said, “we slashed her tires,” and called Parra a “f— dyke” who “looks like a dude,” according to excerpts of the recording included in police records.

Two students told police they heard the freshman say he vandalized the motorcycle, the records show. He lived in the dorm where Parra was a residence hall officer, and his key card showed that he had exited a doorway of the building, just steps from the motorcycle, around the same time the crime occurred, according to the records.

The case was referred to the Solano County district attorney’s office, which said it declined to file charges because it could not prove the allegation “beyond a reasonable doubt.”

A Title IX investigation, a separate administrative process conducted by Cal Maritime, concluded in July that a preponderance of the evidence showed that the freshman harassed Parra in violation of CSU policy, case records show.

Cal Maritime officials declined to say whether the cadet was disciplined and whether he is still on campus, citing student privacy. But Parra was told that the student is no longer enrolled. He could not be reached for comment. Officials also said that Cropper and his leadership team strongly denounced the misconduct.

The campus said it paid $500 to Parra to cover repair costs, but the student said the money covered only a fraction of the damage costs and that the motorcycle has not been used since.

Parra, 23, a junior who wants to be a third mate on a research ship, continues to process the trauma.

“I’m the one that had to pay the price.”

::

In November 2021, a cadet who is Black received anonymous text messages filled with racist, sexist comments that were also laced with threats of physical and sexual violence.

“Would love to put a lynch around your neck,” one message said.

The woman asked who was sending the message. The response: “Massa … Know your place n—.”

Carissa Lombardo, a sergeant in the New York National Guard, was one of several commandants who oversaw Cal Maritime’s Corp of Cadets at the time.

In a phone interview from East Africa, where Lombardo is on military duty and assigned to an air transport operation, she recalled being told repeatedly by supervisors that female cadets needed to be more aggressive in reporting misconduct, which she says signaled a failure to understand the concerns and mistrust that people have in the system.

After learning about the racist and sexist messages, she said she pushed for top administrators to schedule campus conversations to “discuss why this is happening” and “hold people accountable.”

“This was like the breaking point of my morals and values and where I stand as a human being and as a female — and a female in a male-dominated organization,” Lombardo said.

When officials did not hold the conversations, Lombardo said, she sent an email that called out senior administrators, cadets and staff.

“Where are you in putting a stop to ALL hate,” she said in her message. “If you are a bystander to this behavior, you are just as guilty as the cadets who are posting.”

The email included a censored version of the message sent to the woman, whom Lombardo said gave permission to post the rant.

The day after Lombardo sent her message, internal campus records reviewed by The Times show, she was suspended for 15 days, ordered not to set foot on campus and informed that she was under investigation.

Lombardo was accused of using the campus email system in an “unauthorized manner,” according to a memo from Michael Martin, an associate vice president who oversees diversity and inclusion on campus.

Lombardo, who was in National Guard training at the time, said she was locked out of her email and found out on Nov. 19 via a text message from her supervisor that she had been suspended.

The action was condemned by students, who said it reinforced their mistrust of senior administrators, and by faculty senate leaders who wrote a letter calling it retaliation that would create a “profound chilling effect on the discourse that must occur for this university to move forward.”

The campus disputed that Lombardo’s suspension was retaliation, but declined to discuss the investigation, saying it was a personnel matter. Campus police investigated and learned that the messages had been sent from a “burner” phone that could not be traced, officials said in a statement.

Lombardo said she received hundreds of supportive messages from cadets, parents, faculty and staff.

“I feel I was suspended for not actually doing something wrong, but [for] calling the school out for covering up a situation,” she said.

She said she maintains regular contact with cadets who continue to describe a toxic campus culture. For real reforms to occur, according to Lombardo, change needs to “start from the top.”

“When the top doesn’t hold people accountable to these [higher] standards,” she said, “then the change is not going to happen.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.