A top LAFD official fled a crash but got rewarded instead of disciplined

Late on a Sunday night, Ellsworth Fortman, an assistant chief for the Los Angeles Fire Department, walked out of Marci’s Sports Bar and Grill in Santa Clarita and climbed into his Dodge Ram pickup truck for the drive home.

Fortman had traveled less than a mile when he slammed into a parked Toyota Corolla, propelling it 160 feet into a parked Mercedes-Benz. Fortman’s truck careened into a curb and toppled a streetlamp, sending live electrical wires onto the pavement. He then backed up and barreled off.

The events of that January 2020 night — documented in LAFD and law enforcement reports — led the district attorney’s office to charge Fortman with misdemeanor hit-and-run and driving without a valid license. An internal inquiry concluded that he was under the influence of alcohol at the time of the crash, failed to ensure no one was injured before fleeing and put the public in danger from the fallen electrical lines, a Times investigation has found.

The inquiry recommended that Fortman face a Board of Rights hearing, a proceeding that could result in a lengthy suspension or termination, previously undisclosed LAFD records show.

But no discipline was imposed.

Instead, the department gave Fortman a lucrative assignment as a manager of Mayor Eric Garcetti’s COVID-19 testing and vaccination program. Over a period of two years, he made $354,000 in overtime in addition to his annual salary of $221,500.

The LAFD did not begin to schedule a Board of Rights hearing for him until March of this year, which was after The Times began inquiring about the matter. By then, more than two years had passed since the crash.

Critics inside and outside the department say the Fortman case is a stark illustration of a long-standing LAFD pattern of moving slowly to discipline members of all ranks and applying less stringent punishment to chief officers than to other employees, particularly nonwhite and female firefighters.

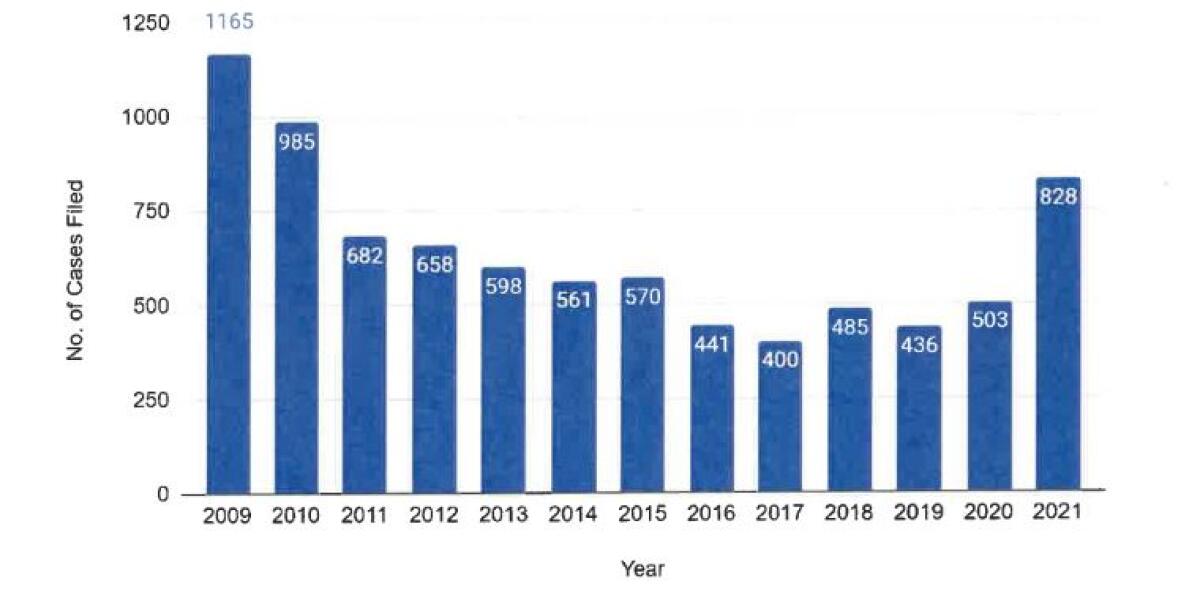

Discipline of any kind in the department is uncommon, and severe discipline more so, including for offenses such as domestic violence and resisting and battering a police officer. In 2020 and 2021, a combined 1,450 complaints of misconduct were filed against LAFD employees, according to the agency. Just 62 employees received any type of punishment during that period, department records show. Because the department’s records are opaque, it is unclear how many of the disciplined employees were accused of wrongdoing in 2020 and 2021 rather than in earlier years.

A recent report by the LAFD’s Office of the Independent Assessor showed that no punishment was imposed in more than 90% of the roughly 1,900 disciplinary cases that were closed last year and from 2017 through 2019, combined. The report said figures for 2020 were not compiled because of the office’s heavy workload that year.

Long delays in the disciplinary process have created a “crisis” backload of more than 70 cases pending a hearing before a Board of Rights, according to the report.

“The result is few people are being held accountable for misconduct, sending a message that discipline is rarely imposed,” the report stated.

That message was underscored in the Fortman case, say the critics, including representatives of organizations of nonwhite and female firefighters. They say that when a member of the brass is accused of bad behavior, the department’s top administrators often either look the other way or slow-walk disciplinary proceedings until the LAFD statute of limitations expires or the officer facing punishment retires.

Fortman, who denied being drunk at the time of the crash, retired days after his hearing was about to be placed on the calendar. He departed with a payout of about $128,500 in what the LAFD termed unused sick leave and vacation time. His annual pension is more than $214,000, city officials said.

A timeline of the crash involving LAFD official Ellsworth Fortman.

Jimmie Woods-Gray, president of the Fire Commission, a civilian panel that oversees the LAFD, condemned the department’s actions in the Fortman case.

“It shouldn’t have happened the way it did,” said Woods-Gray, who has publicly criticized the department’s disciplinary system. “I hope it never happens again.”

Through his attorney, Michael Raab, Fortman declined to be interviewed. Raab said in an email to The Times that Fortman received “no favorable treatment” from the LAFD and that “his discipline proceeded according to all appropriate rules and regulations.”

LAFD spokesperson Cheryl Getuiza defended the department’s handling of the Fortman episode. She said in an email to The Times that the disciplinary process was delayed because the LAFD’s “investigatory practice is to wait for a criminal case to close before moving forward with our administrative investigation,” and because Fortman “was deemed critical to the success of the Covid testing and vaccination effort.”

Getuiza said the department also had waited until after Fortman completed the terms of an agreement he struck with the court to resolve the criminal charges, which included community service.

But records obtained by The Times show that the department’s Professional Standards Division began its investigation soon after the hit-and-run and reached its conclusion six months before Fortman arrived at his deal with the court.

Getuiza later reversed her position on the Fortman case, saying in an email, “There was no delay in the administrative investigation.” Asked whether anyone else in the department could have replaced Fortman in the COVID program, Getuiza did not respond directly but cited the large number of tests and vaccines the city administered.

She did not respond to a hypothetical question of whether the LAFD would wait to impose discipline until after a firefighter completed a jail sentence or a term of criminal probation, for example.

::

The newly unearthed records and earlier reports from the Sheriff’s Department provide a detailed description of the crash and its aftermath.

Sheriff’s deputies summoned to the scene found among the wreckage the license plate from Fortman’s pickup. They traced the license number to Fortman.

At the crash scene, a GMC Terrain slowly approached the wreckage, and a woman in the vehicle asked what happened. “Oh, my God!” she said after being told about the hit-and-run, an LAFD investigative report states. The GMC pulled away and a deputy noticed it had a firefighter decal on the rear window. That prompted the deputy to follow the GMC in his patrol car, pull it over and ask the woman if she knew who was driving the Dodge.

According to the report, the female passenger told the deputy that she was Fortman’s girlfriend and said, “I know this is bad! He’s an assistant fire chief. It’s bad!”

The report states when asked if she knew whether Fortman had been drinking, the woman said, “I’ll be real with you, he’s probably drunk.”

The woman, whose name was redacted from the investigative records, shared with the deputy text messages Fortman sent her that said “call me,” “accident,” “hurry,” “call me.”

At Fortman’s home, deputies found the damaged Dodge truck in the driveway and had it impounded. One of the deputies heard Fortman speaking on the phone in a side yard and called out to him that he was from the Sheriff’s Department.

Fortman ignored him.

The demand for a federal investigation follows a Times report on allegations that a high-ranking white official received preferential treatment after he was reported to be under the influence of alcohol or drugs while on duty.

The deputy repeatedly pounded on the door, shouting, “Sheriff’s Department, Sheriff’s Department.” Visible to the deputy through the door’s glass panel, Fortman walked into the house and climbed the stairs to the second floor. He never came to the door, and the deputy eventually gave up.

The Sheriff’s Department previously said the deputies did not enter Fortman’s property to arrest him because they considered the incident a misdemeanor. Obtaining a misdemeanor arrest warrant at such a late hour — it was after 10:30 p.m. — is difficult, a Sheriff’s Department spokesman told The Times days after the crash.

At a deputy’s request, Fortman’s girlfriend entered the home to speak to Fortman. She returned and told the deputy that Fortman had contacted an attorney, would not come out of the house and had not been drinking before the hit-and-run but had started to drink after arriving home.

In his report on the incident, the deputy wrote, “The only reason why he would leave the scene of the collision, and refuse to speak and hide from police, was to avoid being arrested for a DUI.”

The next morning, Fortman visited the home of Alyssa Ward-Vela, the owner of one of the damaged cars, to say he was responsible for the incident and give her his insurance information. Ward-Vela’s aunt, Kimberly Ward, said Fortman told her he lost control of the truck because he had diarrhea and had been vomiting.

According to Ward and the newly released records, Ward-Vela felt menaced by Fortman because he later appeared outside her home to confront a television news crew that was reporting on the hit-and-run. Ward-Vela subsequently obtained a temporary restraining order against Fortman, court records show.

The LAFD records state that Fortman denied confronting the news crew and that the temporary restraining order was dismissed after mediation with Ward-Vela.

The sheriff’s investigation found a receipt that showed Fortman had bought a beer at Marci’s, a sports bar, and closed his tab there about 10 minutes before the hit-and-run, according to the LAFD records. Later, the documents state, Fortman told LAFD investigators that he had visited another bar earlier in the day, and that he had four to five drinks during the six or seven hours before the incident, but was not drunk.

He also said he felt he had no legal obligation to speak to the deputies who went to his home the night of the crash because they already knew who he was and had impounded the Dodge, according to the LAFD investigative report.

A second deputy is quoted in the report as saying Fortman, at the time of the hit-and-run, “was intoxicated” and claimed to have begun drinking only after he was home so he would have an excuse if he failed a subsequent blood-alcohol test.

L.A. Mayor Eric Garcetti has made increasing the number of women in the Fire Department a major goal. Some senior women in the LAFD, and his own appointees, say the mayor could be pushing harder.

The report further recounted an unidentified witness as stating the hit-and-run put passersby in danger; the witness said, “there were live wires, people walking around them, they could have been deadly, and the power company moved everyone away when they arrived.” One of the sheriff’s deputies said, “Someone could have been electrocuted,” the report states.

The Times obtained summaries of an LAFD investigator’s interviews of Fortman, the first conducted about six weeks after the hit-and-run. In the summaries, Fortman described the incident as “unfortunate because it was unfortunate,” denied being intoxicated and said the person knocking on his door that night did not identify himself as a sheriff’s deputy.

The documents say the investigator related the girlfriend’s reported comment that he was “probably drunk,” and Fortman responded, “She did not say that.” Asked if the deputy lied in his report about that, Fortman said, “Yea,” according to the summaries.

He also said he did not start drinking once he returned home or call a lawyer that night but his sister might have contacted an attorney, the LAFD investigative report states.

Near the end of the second interview, Fortman is quoted as saying he wished he had managed the incident better and “deeply honestly” regretted fleeing the scene. And when asked if he had brought discredit to the department, he is reported to have replied, “Yes.”

It was around the time of the first interview by the investigators that Fortman began collecting overtime at the COVID-19 task force. And he was still facing potential criminal charges.

A November 2020 report on the LAFD’s inquiry proposed that Fortman be brought before the Board of Rights. The inquiry concluded that in addition to fleeing the scene, he was under the influence of alcohol, failed to ensure no one was injured and brought discredit onto the department. The following month, the LAFD filed its formal internal charges against Fortman. That should have led to the Board of Rights hearing at which punishment, if any, would have been determined.

In May of last year, and in exchange for the dismissal of the criminal charges against him, Fortman entered into a court-supervised diversion program that required him to make restitution for the property damage he caused, perform community service and attend Alcoholics Anonymous meetings.

Fortman was licensed as a paramedic by the California Emergency Medical Services Authority. Records obtained by The Times show that the authority in August 2021 hit Fortman with the maximum possible fine for his conduct: $2,500. The agency found that Fortman violated a state code that forbids the “commission of any fraudulent, dishonest, or corrupt act which is substantially related to the qualifications, functions, and duties of prehospital personnel.”

But the LAFD still did not set in motion a Board of Rights hearing.

“It makes me sick,” Ward said, when informed that Fortman had evaded discipline. “He was not held to a certain standard that everybody else is. It’s the way of the system.”

::

Controversy over how the LAFD deals with problem employees is nothing new. Audits dating to 1994 have found the department’s disciplinary system to be plagued by uneven punishment in the ranks, faulty documentation of complaints and unreasonable delays in imposing penalties. A 2010 report by the LAFD’s independent assessor found that some allegations of misconduct were ignored and others were allowed to languish until the statute of limitations expired.

The president of Los Angeles Women in the Fire Service, Battalion Chief Kristine Larson, said delays of months and even years in imposing discipline — to the point where those facing punishment could retire — have long been a problem among all ranks of LAFD firefighters. But it was especially pronounced among officers during the tenure of former Fire Chief Ralph Terrazas, who retired in March after 7½ years in the top job, Larson said.

“He just did not believe in disciplining people — or certain people,” she said.

An outside investigation found that Chief Deputy Fred Mathis was likely intoxicated but cleared him through a rationale that has outraged department insiders.

Rebecca Ninburg served as an appointee of Mayor Garcetti on the Fire Commission from 2016 until August of this year.

“With the prior chief, top to bottom, there was no accountability whatsoever,” she said. “The discipline was doled out unevenly. If they don’t like you, they throw the book at you. If they do like you, you get a pass.”

Ninburg placed much of the blame on Garcetti, who she said “caved” to the demands of the LAFD’s two unions. “He just would never say no to them,” she added. The leaders of the chiefs union declined to comment, and the head of the rank-and-file union did not respond to a request for comment.

Terrazas did not respond to messages seeking comment. Neither did Garcetti.

The L.A. Fire Department’s top administrative commander reportedly appeared to be intoxicated at work during the Palisades fire, records show.

Fire Chief Kristin Crowley, Terrazas’ successor, has been hailed by supporters as a reformer in the making. But she declined to discuss the Fortman case, saying in an email that she “will not be commenting on the previous administration’s decisions.” Under Terrazas, Crowley served as fire marshal and deputy chief.

From roughly the time of the hit-and-run to Fortman’s retirement, the LAFD disciplined 79 employees, according to reports to the Fire Commission.

Five of the cases involved traffic accidents, and larger numbers resulted from misconduct that roughly echoed the allegations against Fortman. They included conduct unbecoming a firefighter, alcohol abuse and violating emergency medical service protocols. The internal inquiry alleged that Fortman breached the EMS protocols by fleeing the crash scene.

The commission reports contain no names and provide only brief summaries on the misconduct. None of the reports states that an employee had been charged with a crime, although one firefighter was suspended for four days for not informing the department of being named a suspect in a crime and five others were punished for alleged domestic violence. Ranks in the documents are reported in the broad categories of officer and non-officer, with the former meaning battalion chief and higher.

Forty-nine of the cases resulted in reprimands, 26 in suspensions and one in a firing. Three of the firefighters resigned, one of whom faced termination. Ten of the firefighters were officers. They included the lone employee who was fired — for an offense described only as “failure to meet conditions of employment.”

Deputy Chief Fred Mathis was under investigation for allegedly being intoxicated at work when he accessed the LAFD’s complaint system, according to the department.

The stiffest penalty imposed in the domestic violence cases was a 26-day suspension. The unnamed employee also drove with a blood-alcohol level of more than twice the legal limit and resisted and battered a police officer, according to LAFD records.

Around the time Fortman was settling his hit-and-run criminal case, a high-ranking LAFD officer reported to her superiors that the department’s No. 1 administrative commander appeared to be intoxicated while he was overseeing the agency’s operations center during the Palisades fire. Several LAFD members told The Times that the department initially tried to cover up the allegation against then-Chief Deputy Fred Mathis, who said he did nothing wrong.

Rather than have his office investigate, City Atty. Mike Feuer farmed the inquiry out to a private law firm. LAFD critics labeled that a stalling tactic and predicted that it would allow Mathis to avoid punishment by retiring or running out the clock on the statute of limitations.

The announcement by the U.S. attorney’s office comes amid calls by groups representing Black, Latino and female firefighters for an investigation into allegations of discrimination against L.A. city fire employees.

Eight months later, the law firm concluded that Mathis was likely intoxicated on the day in question, but it cleared him through a rationale that outraged department insiders: It found that Mathis was “technically off duty” at the time because he declared himself out sick.

Mathis retired within days of the firm’s findings and collected a $1.4-million payout in what the department said was unused leave for vacation, illness and holidays.

Some critics contrasted the LAFD’s treatment of Mathis, who is white, with that of a low-ranking Black firefighter who was forced to resign last year after being accused — falsely, the firefighter asserted — of missing a mandatory Alcoholics Anonymous meeting.

He had been required to attend the meeting because of a drunk-driving arrest many years ago.

The Mathis case prompted the leaders of two organizations for Black and Latino firefighters as well as Larson’s group for women to demand a federal investigation of what they said was long-standing racial bias in how the LAFD imposes discipline and awards promotions. The U.S. Justice Department subsequently said that it was “carefully reviewing” the complaints, but it has taken no public action in the 15 months since and has declined to comment on the status of any probe.

In the meantime, said Larson, higher-ups continued to escape punishment after being accused of misconduct.

“A lot of the chief officers skated,” she said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.