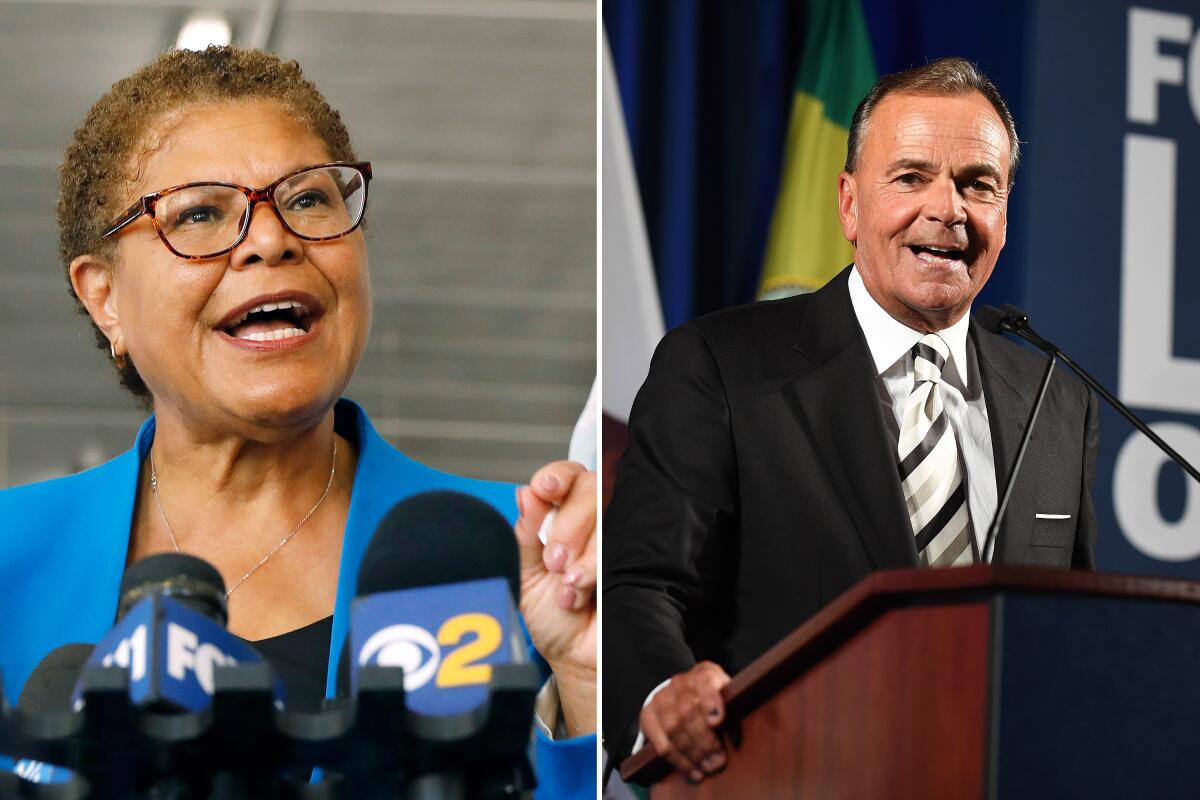

Column: L.A., it’s time to choose a mayor. Is it Bass’ moment, or Caruso’s?

After months of jockeying, an epic City Hall bigotry scandal, extended drought and monsoons of television ads, the great and troubled city of Los Angeles, 4 million strong, straddles a fault line as election day looms, deeply divided over the choice of its next leader.

There is Karen Bass, who’s had three public service careers — first in healthcare, second in community organizing, third as a lawmaker in Sacramento and Washington.

And there is Rick Caruso, the lawyer-turned-business mogul and philanthropist who made a fortune reinventing a classic California cultural institution: the shopping mall.

In something of an irony, each represents a declining demographic in a city now roughly half Latino. The latest poll gives Bass a tiny but shrinking lead among likely voters, with a smallish 13% undecided on stewardship of a rambling metropolis in which mega-mansions share ZIP codes with tent cities.

Through the primary and beyond — with homelessness, affordable housing, trashed streets and crime all dissected in the town square — I’ve found residents to be pretty fixed on who they liked and trusted.

“I mean, he’s not a politician,” Andrea Burman told me in May at the Northridge Fashion Center, where she said that on all the big issues, Caruso is the obvious choice.

“We want change,” Caruso supporter Chester Chong told me last month in Chinatown, where he introduced Caruso as the man who can deliver what City Hall has not.

Law student Miriham Antonio, who ran a voter registration drive when she was a student at Fairfax High and later worked part time for various public officials, said she understands Caruso’s outsider appeal. Homelessness has gotten worse in her Koreatown neighborhood, she said, and frustration with City Hall has mounted over that, affordable housing and crime.

And yet Antonio — who was irate over the City Hall scandal that exposed grievances against Black and Oaxacan people, among others — thinks Bass is best primed to move the city forward.

“Her background shows she cares about building coalitions,” said Antonio, who also likes the idea of having a woman of color lead the city.

From the moment Caruso stepped into the race, Bass has been running against both him and his money. Caruso has poured tens of millions into advertising and door-knocking campaigns, outspending Bass by 13 times and creating something of a David and Goliath scenario.

I had lunch recently in North Hollywood with Jeffrey Katzenberg, co-founder of DreamWorks and former chair of Walt Disney Studios, who has donated nearly $2 million to an independent expenditure committee called Communities United for Bass. To most people that’s a small fortune, but it’s a paltry sum when stacked against the Caruso expenditures, which have approached the price tag on his $100-million yacht.

Also at that lunch was Matt Johnson, an entertainment lawyer and Bass supporter who, like Caruso, once served as a Los Angeles police commissioner. The revelation earlier this year that Caruso had missed 40% of the meetings when he was a commissioner didn’t sit well with Johnson.

Rick Caruso and Karen Bass are running for Los Angeles mayor. Here is your guide to the race.

“Your most basic responsibility is showing up every week and showing up on time,” Johnson told The Times earlier this year.

At our lunch, Katzenberg and Johnson said they think Caruso’s plans to hire 1,500 more police officers and house 30,000 people in 300 days are preposterously not implementable, no matter how much money the candidate spends trying to convince voters otherwise.

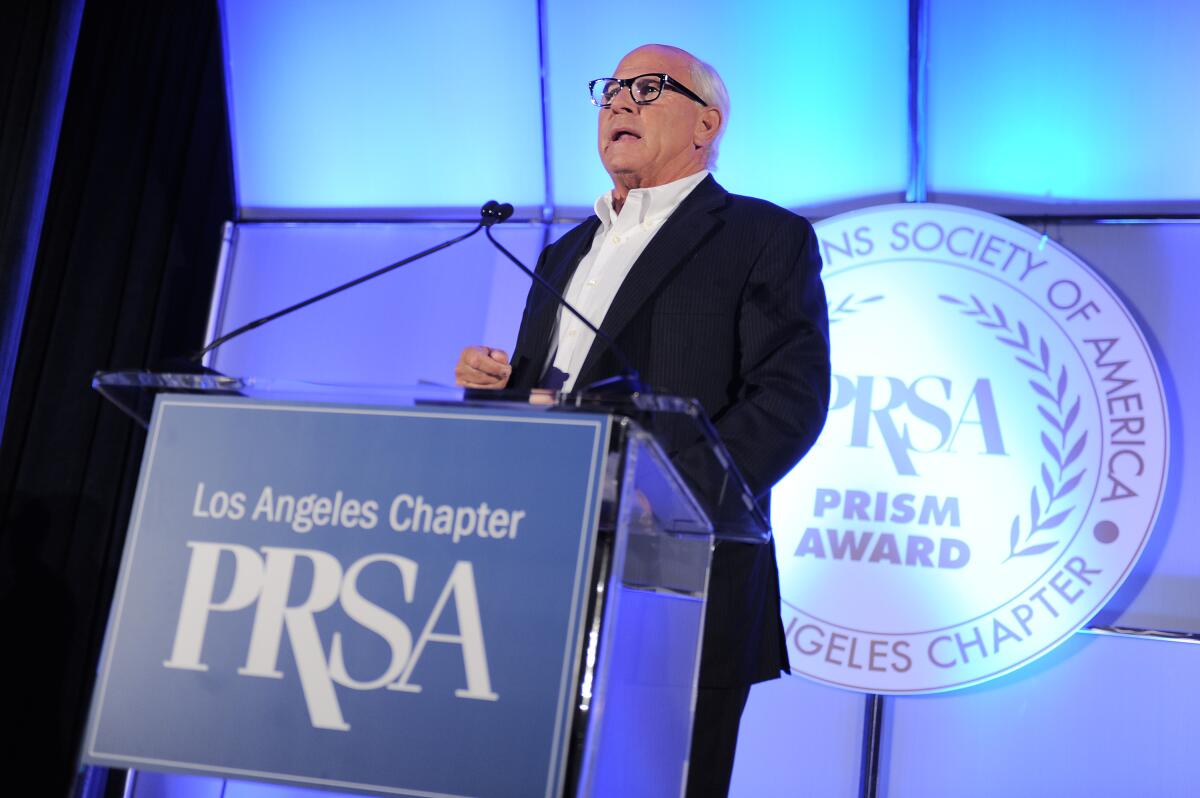

Another high-profile Bass supporter, developer Steve Soboroff, also served on the police commission and spent more than an hour explaining why he likes Bass, even as he downed a No. 19 pastrami sandwich at Langer’s Deli in MacArthur Park. In fact, Soboroff brought scribbled notes with him, highlighting examples of personal interactions with Bass that made him trust and admire her.

The first came in the 1990s, when Soboroff served on a school bond oversight committee and Bass was working as co-founder of Community Coalition, which was established to organize Black and Latino residents and lobby for needed services.

Bass argued that in deciding how to spend the bond money, the oversight committee ought to consider the perspectives of students. So she brought two dozen kids from different schools to a meeting, Soboroff said, and they made their case, having done their own interviews with janitors and the providers of arts programs.

“That was my first experience with her and she was remarkable,” said Soboroff, who recalls that money was moved out of a budget for “repaving parking lots that didn’t need it” and instead was plowed into some of the programs the students wanted.

The second experience involved Soboroff’s time on the city’s parks commission. There was a proposal to keep the lights on at night for supervised activities at rec centers, with the goal of keeping kids safe and tamping down neighborhood crime. Soboroff said he knew Bass had created a successful program along the same lines, and told the city to copy her plan before approval was granted.

Soboroff, who served as a Big Brother during his college years in Arizona and later got involved in the program, also became a foster parent. He said he tapped Bass’ experience in those fields, which she spent considerable time on in Washington while reforming the nation’s antiquated child welfare system.

“Rick is charismatic,” Soboroff said. “When he walks into a room, he sucks the air out of the room … but that means nobody else can breathe. We don’t need that right now.”

The city needs a collaborator with close allies in Sacramento and Washington, all the way up to the president’s office, he said, and that’s what Bass will bring.

“This is her moment,” Soboroff said.

Equally ardent about their candidate, Caruso, are four women I met in South Los Angeles, including three victims of street violence.

“My only son was murdered,” said LaWanda Hawkins, speaking of 19-year-old Reginald.

“I was shot four times in Nickerson Gardens on May 27, 2007,” said Rose Smith, who uses a wheelchair and told me she still has a bullet embedded in her jaw.

Barbara Pritchett, wiping away tears, said her two sons — DeAndre, 30, and Dovon, 15 — were shot dead nine years apart. Pritchett and the other women said the motives remain a mystery.

Two of the women said they were in Bass’ camp before Caruso entered the race, but they didn’t hesitate to switch their allegiance. They don’t have much faith in those who have held public office, because crime, homelessness and other issues aren’t getting any better despite years of promises.

The women have developed personal relationships with Caruso, who supports a number of nonprofit community service centers, including Strive in South L.A., where I interviewed the women.

When Caruso arrived, he exchanged hugs with each of the women. Hawkins held up her phone and said she has his cell number and can call if she needs anything. Smith said Caruso has helped send her daughter to private school.

“Do you know how much that means to us in the community?” Smith said. “That means the world.”

But Caruso is promising to be there for every community. Can he deliver? I asked.

He’s already delivered, the women said.

Advocates, outreach workers and homeless people on skid row want coherent plans from candidates, not big promises.

For the record:

11:10 a.m. Nov. 5, 2022An earlier version of this article misspelled Snoop Dogg’s last name as Dog.

Since early in his campaign, Caruso has frequently cited two supporters in particular: Snoop Dogg, and Sweet Alice Harris. I couldn’t hook up with Snoop, but Harris was open to a visit at the South L.A. nonprofit she has run for almost 60 years, Parents of Watts.

Harris was seated on the front porch when I arrived and she led me inside her office, a converted house, the walls plastered with awards in her name and photos of presidents she has met — Carter, Clinton, both Bushes, Obama. Harris wore an “I Voted” sticker and said she’d given her support to the man she first met a couple of decades ago, when Mayor Tom Bradley dropped by with Caruso.

“He had told me … whatever I want, let him know, so I don’t feel bad asking him for what things we need,” said Harris, who is planning to give away 80 turkeys for Thanksgiving and 400 bicycles for Christmas.

Harris said she grew up poor in Alabama and knows all about the mental anguish that brings, so that’s why she started Parents of Watts. She said that while many politicians and luminaries have dropped in or sent support, she has never met Bass, whose congressional district does not include this area.

“I voted for Rick because I know he’s going to help us,” said Harris, who spoke of a recent visit to skid row. “Do you know how many homeless people are laying on the streets dying? I cried for three days. Pitiful, pitiful, pitiful. That should not be. It should not be.”

Harris was busy coordinating mental health services with a visitor, so I didn’t stay long. I thanked her for the visit and drove north on surface streets, up the spine of the city and through skid row, which shocks every time and begs relief.

Is it Bass’ moment, as Soboroff suggested? Or is Sweet Alice’s faith in Caruso well-placed?

Soon, one of the two will take on the glory and the grief for the next four years, and maybe eight, with massive challenges to tackle, voter expectations high and patience running on empty.

In Los Angeles, the race comes to a close, a new era begins.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.