His website skewers Stockton politicians and agencies. Then one gave him a cushy job

STOCKTON — As traditional media fade, the lines have become fuzzy on what constitutes a journalist, including here in the heart of the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta.

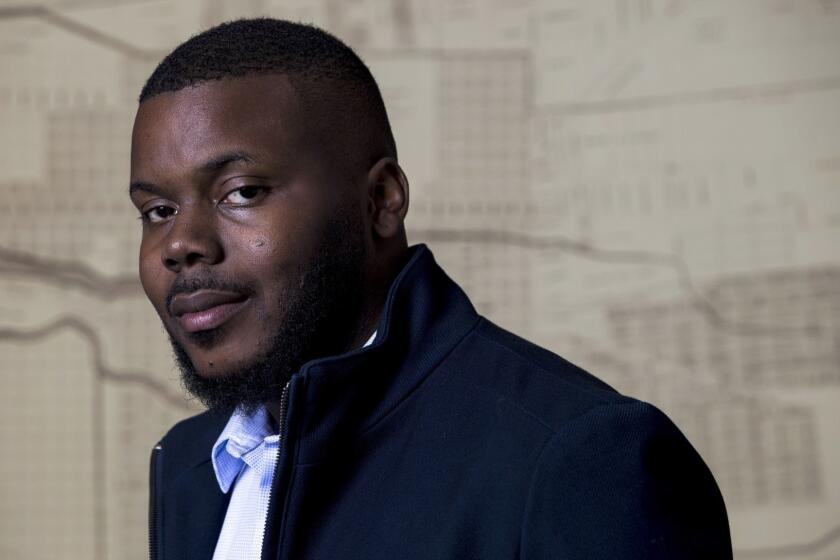

In Stockton, Motecuzoma Patrick Sanchez runs 209 Times, a news site that has gained a sizable following as it punishes Sanchez’s enemies, rewards his friends and often celebrates the work of its owner and founder.

Sanchez recently flogged a school board member as “Devil” Ann. His 209 Times belittled a nonprofit leader as a “Karen.” Another political foe had a photo of his face superimposed on a toddler’s body. The site depicted Gov. Gavin Newsom as a pimp and labeled state Sen. Susan Talamantes Eggman (D-Stockton) as “anti-Mexican,” with Sanchez quoted in the story as if he were an independent observer. When adversaries counterattacked via social media, calling Sanchez “Mo-tricks,” he lashed them as “the roach pack.”

Political leaders and civic activists have long blamed 209 Times and its related social media platforms for poisoning political debate in a community that is already economically challenged. But in the last year, Sanchez has become enmeshed in the power structure that he purports to hold accountable. While still in control of his 209 Times — named after the local area code — Sanchez now holds a well-paying administrative job at the Stockton Unified School District, where the leaders who hired him enjoy positive coverage from his news site.

He’s also opened a consulting business serving politicians, at least three of whom have received doting treatment from 209 Times and his other sites.

These potential conflicts stand outside the norm of mainstream journalism. To detractors, they reflect what can happen as newspapers and broadcasters struggle and “citizen journalists” rush in to fill the vacuum, sometimes bringing personal allegiances and vendettas with them.

“The 209 Times is getting away scot-free with character assassination,” said Michael Fitzgerald, a former columnist with the Stockton Record newspaper who now writes for a local media startup, Stocktonia.org. He accuses 209 Times leaders of “toxifying Stockton’s civic culture for their own twisted purposes and their own gain.”

Benjamin Saffold, a community activist, agreed with that assessment. “Motec and others have actually replaced the so-called ‘cabal’ that was voted out,” Saffold wrote in a recent online posting. “He has used his new power to benefit himself in the same way that he accused those who preceded him.”

Sanchez rejects claims that 209 Times has done anything but inform and empower his hometown. In an email, he blamed an “old guard” of developers, corrupt politicians and their enablers — including outside media like The Times — for manufacturing controversy and seeking to discredit his community endeavors.

“I have been and will continue to wage war on them and their agents and organizations,” Sanchez said in the profanity-spiced email. “Nothing your little article will do will stop that. Nothing. All roads will continue to lead to me in my city.”

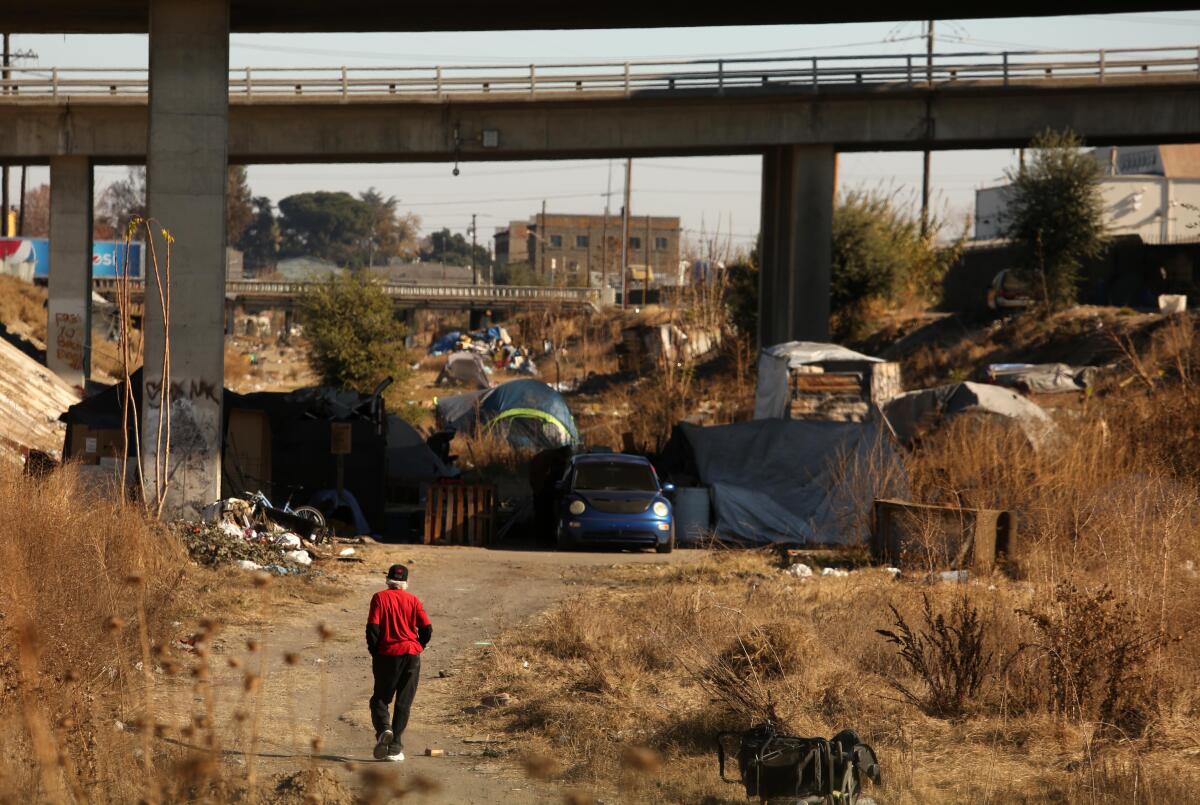

Sanchez’s profile in Stockton has risen partly because of the hard times the city has suffered, leaving residents hungry for heroes, and villains. With its high crime and unemployment rates, Stockton was listed by Forbes in 2010 as one of the three worst U.S. cities in which to live. In 2012, the city filed for what was then the nation’s largest municipal bankruptcy.

The Stockton Record newspaper has lost audience and seen its staff downsized in recent decades. That follows a national trend that saw newspaper circulation in the United States drop from 112 million to 68 million in the 15 years before 2019, according to a University of North Carolina tracking project.

Sanchez started 209 Times as a for-profit company in 2016. The website says its mission is to “take on the issues that the corporate owned media are either too scared or too compromised to address.” Much of the material comes from a dozen “guerrilla journalists” who work on part-time stipends, Sanchez said in a 2021 interview with NPR.

Many recent offerings from 209 Times (most often found on the site’s Facebook page) lean more police blotter than hard-hitting investigative journalism. They include a story on the 20 cats rescued from an allegedly abusive owner. Videos of vehicles on fire abound. Perhaps the site’s biggest hit of the last year: video of a man twerking in tiny cutoff jeans, while walking on Interstate 5. It drew nearly 8 million views.

209 Times simultaneously wins praise, and followers, by posting fundraisers for families in need, publishing alerts for missing community members and congratulating everyday heroes who have, for instance, made daring rescues or won academic contests. “This is so heartwarming,” a reader enthused recently when Sanchez came to the aid of a needy veteran.

The media outlet first gained nationwide attention when pundits credited it for helping to eject Stockton Mayor Michael Tubbs — a rising star in Democratic circles — from office in 2020. 209 Times published unverified allegations that Tubbs, among other things, had misappropriated millions of dollars earmarked for city programs. The site offered no proof for these claims, and the Tubbs camp called them “outright lies,” but the incumbent ended up losing narrowly to a novice Republican candidate, Kevin Lincoln.

209 Times has since focused on other targets, most notably San Joaquin County Dist. Atty. Tori Verber Salazar.

An opinion piece by contributor Frank Gayaldo exemplified the criticism. It accused other public officials of conspiring to “weaponize code enforcement against business owners in a discriminatory and retaliatory fashion.” Then, without providing proof, the piece asserted that the accusations, “if true,” showed that Salazar’s office “tacitly supports” a “209 Culture of Corruption.”

Salazar clearly faced other headwinds in her reelection bid, including a no-confidence vote by a group of prosecutors in her office. But the candidate found it hard to beat back a drumbeat of 209 Times put-downs. With the district attorney apparently defeated in June, 209 Times crowed: “She will join a long list of high profile elected officials … eliminated as a direct result of our educating the community.”

Asked in a 2021 interview with NPR if 209 Times had at times hit “below the belt,” Sanchez did not disagree but added: “There’s never been a time it wasn’t warranted.”

When coming under criticism or scrutiny, Sanchez often goes on the offensive.

After a Times editorial criticized his news operation and a reporter started asking questions last year about 209 Times’ practices, Sanchez showed up at The Times’ El Segundo headquarters, unannounced, demanding to meet with the paper’s owner, Dr. Patrick Soon-Shiong. Turned away by security guards, Sanchez memorialized his visit on Twitter. “I heard the racist @latimes was looking for me. So I went to them. Aquí estoy,” he wrote.

A year ago, a high school honors student named David Sengthay led student protests against school district leaders. His critiques of the district continued, while he also became a prominent supporter of a City Council candidate loathed by 209 Times.

209 Times has responded with scathing critiques of the 17-year-old, who graduated in May and is headed to Stanford. It accused him of being part of a group of “clowns,” said he was “being groomed by adults” to attack the district and charged that he runs a provocative social media page that bashes the district (and also 209 Times).

Questioned about lambasting a minor who recently attended the district where he works, Sanchez has depicted himself as the victim. The teenager was presented with a cease-and-desist letter that insisted he had been “maliciously spreading inaccurate and unfounded information” that had harmed Sanchez’s character. The letter holds up the threat of a future lawsuit against Sengthay’s parents (as the allegedly responsible parties) and the whole episode immediately became the subject of a 209 Times story.

Sengthay denies he operates the social media page that has attacked the district and Sanchez. He has filed a police report for harassment. “This is just the most recent example,” Sengthay said, “and it seems very clear that Mr. Sanchez has demonstrated he is willing to attack anyone who he thinks stands in his way.”

Although 209 Times bashes many progressives, Sanchez notes that he supported U.S. Sen. Bernie Sanders and insists he’s an equal-opportunity offender of the powerful. “We tell everyone we’re biased,” he wrote in an email to The Times, “and provide documents and evidence for the public to review on their own.”

Yet although he may not be a Trump acolyte, Sanchez has adopted some of the tactics of the former president, deploying his megaphone to pummel what he calls “enemies” — to a degree that many politicians hesitate to publicly criticize 209 Times.

Stockton Mayor Michael Tubbs, 30, faces a possible reelection loss to a first-time mayoral candidate after coming under attack from a popular local website run by a man with a grudge against Tubbs.

The news site ran video of San Joaquin County Supervisor Kathy Miller walking in her neighborhood on a weekday, with Sanchez calling out to her from a car, questioning why she wasn’t in her county office. The story didn’t acknowledge that during the pandemic employees commonly work from home, and aren’t confined to their desks.

“I think they have lowered the political climate. They have harmed good people,” said Miller, who is leaving office this year after serving the maximum two terms. “They are part of the dumbing down of our county and our country. I don’t think this is the only place in the United States that’s losing legitimate media. It’s just really hard when it’s your community.”

209 Times has violated convention in other ways. The outlet has not filed a return with the California Franchise Tax Board since 2019, leading to the company being placed on “suspended” status, an agency spokeswoman said. The tax board said a suspended company “is not in good standing and loses its rights, powers, and privileges to do business in California.”

Sanchez explained that as a new business owner he didn’t know he had to file his taxes with the Franchise Tax Board. He said the failure is “being resolved.”

“I think they have lowered the political climate....They are part of the dumbing down of our county and our country.”

— San Joaquin County Supervisor Kathy Miller, commenting on the 209 Times.

In the last year, he has become more deeply embedded in the power structure he purports to watchdog.

Until two years ago, 209 Times had regularly lambasted the leadership of the troubled Stockton Unified School District, savaging Supt. John Deasy — a former L.A. schools superintendent — and some board members.

But when the superintendent resigned and was replaced last year by John Ramirez Jr., the news site’s coverage became more favorable. Sanchez said that was because, after Deasy’s departure, “more positive things are happening in the district and community.”

Ramirez had been credited in his old Monterey County district for helping improve test scores, and 209 Times published a glowing account of his rags-to-riches rise from picking strawberries to earning a graduate degree at Harvard. But it did not delve into details of his work history, including accusations of sexual harassment against two employees — which he has denied — and other concerns.

“None of those issues arose in Stockton, so there was nothing to report on,” Sanchez said, in explaining his outlet’s silence. For his part, Ramirez said the previous claims against him were “unfounded.”

Others saw a different reason for 209 Times’ treatment of Ramirez. Four months after the superintendent came on board, the school district hired Sanchez as director of Family Resource Centers. When The Times first inquired about Sanchez’s pay, a district spokeswoman said he made $149,583. The spokeswoman later corrected that figure to just under $136,000 and didn’t respond to a request for further clarification.

Several employees in the district said they believed that by hiring Sanchez, Ramirez benefitted by drawing a potentially harsh critic close. “That’s one less place writing anything bad about the district now,” said one former district administrator, who asked not to be named, saying she feared retaliation.

Sanchez, 46, scoffed at the notion that 209 Times would pull punches on the school district leaders. “No one tells me or my organization what to do,” he said. Asked through a spokeswoman for a response, Ramirez provided none.

Twice in the last year, the outlet has belittled investigations by the San Joaquin County Grand Jury that found deep dysfunction in the Stockton Unified School District. The first report found that public trust and employee morale had fallen to “an all-time low.” The second said the district was at risk of insolvency.

209 Times’ response to the first report was to urge patience with Ramirez and school board members. The outlet blamed the previous superintendent, claiming he “left the district in a $100 million deficit,” which is different from what the county Office of Education reports. It told The Times the district recorded a $32-million surplus in 2020. Asked about the discrepancy, Sanchez declined to say where 209 Times obtained its $100-million figure, and told a reporter to do his own research. “Not doing your homework for you,” he said in an email.

Asked about 209 Times’ treatment of the grand jury findings, Sanchez attacked the panel as unrepresentative of the community. Asked if 209 Times should tell readers about the apparent conflict of interest, with his 209 Times reporting on an agency that pays his salary, Sanchez responded: “I’m Mexican, I’ve never just had one job. I don’t concern myself with concerns of ‘appearances’ from the biased L.A. Times.”

The response echoed the populist storyline that Sanchez invokes repeatedly, that of a striving young man whose hard work and persistence turned him into a media “revolutionary.”

“I was born in the gutter, everything since has been a come up,” he wrote last year on Facebook, describing his upbringing by a single mother in Stockton, where his public schoolmates recalled him as Patrick Powell or Patrick Sanchez Powell.

An online biography says he served in the Marine Corps in the Middle East, then attended Sacramento State, where he got his bachelor’s in ethnic studies, before receiving a master’s in public administration from USC.

Sanchez wrote that America’s unjustified occupation of Iraq opened his eyes to the need to hold the government accountable. It was during this post-military political awakening that he also rejected the last name of a father he never knew. Identifying more closely with his Indigenous roots from his mother’s side of the family, in Mexico, he kept her last name and chose the first name Motecuzoma. He told interviewers it meant “Wrathful Lord.”

Sanchez has repeatedly failed in bids for elected office, receiving 2% of the vote when he ran for mayor of Stockton in 2008, ending up third in a 2014 run for City Council, finishing last in a 2018 run for the San Joaquin County Board of Supervisors and placing far behind the eventual finalists — Lincoln and incumbent Tubbs — in his second campaign for Stockton mayor.

Sanchez’s animosity toward Tubbs seems unabated to this day. His website argued last year that Harry Black, the city manager hired under Tubbs, should be fired. Black has maintained his job, but observers of Stockton politics believe that could change if a 209 Times-favored candidate prevails in the November City Council election.

209 Times’ loyalties in the first round of voting in June appeared unsurprising, given the ties three candidates forged with Sanchez. Campaign spending reports reveal that the two candidates hired Sanchez’s firm as their political consultant, while a third candidate confirmed that Sanchez had been hired to provide “services.”

Council candidates Brando Villapudua, a sales executive, reported that he paid he paid $1,500 to the firm Tecuani, while candidate and schoolteacher Michele Padilla’s report shows she owed $1,000 to the same firm, which is identified in state records as a company controlled by Sanchez. In addition, both Villapudua‘s and Padilla’s campaign websites say they are “powered by Tlatoani.” State records show that Sanchez is the owner of Tlatoani Consulting.

The two candidates who hired Sanchez’s company received strikingly more positive coverage from 209 Times than opponents who did not hire his firm.

When Villapadua filed his candidacy papers, for example, 209 Times’ Facebook page welcomed him with “IT’S OFFICIAL!” and allowed him to introduce himself. In contrast, it depicted his opponent, Jewelian Johnson, as one of several “allies and agents of failed former Mayor Tubbs.” In one picture, 209 Times superimposed Johnson’s head over a toddler’s body. Nowhere did the posts disclose that Sanchez’s firm was a paid political advisor for Villapudua.

Some readers see Doni Chamberlain and her website as a defender of civil society; others in Shasta County reject her as a liberal ‘laughingstock.’

Padilla also got a friendly introduction to her candidacy and — like many other 209 Times-backed candidates — a fawning video interview with contributor Gayaldo. The outlet posted several articles belittling Padilla’s opponent, Councilman Sol Jobrack, as inattentive and self-serving.

In one post, the word “crooked” is superimposed over Jobrack’s face. A viewer had to read the accompanying story to learn that the councilman had committed no crime; merely that his campaign signs were crooked.

Jobrack led the June voting but fell short of 50% and will face a November runoff. Nowhere had 209 Times disclosed that Jobrack’s opponent had hired Sanchez as her consultant.

Stockton City Councilman Paul Canepa, a candidate for the Board of Supervisors, also confirmed that one of his consultants had hired Sanchez. The consultant, Allen Sawyer, said that $2,000 had been paid to Sanchez’s firm for “political work and outreach with unions.” Canepa has received gentle handling by 209 Times, while his November runoff opponent has been lambasted.

Sanchez insisted that there was no conflict between his political work and reporting on 209 Times, saying there was a “firewall” between the two companies. Asked about why the outlet did not disclose his paid political work to readers, he accused The Times of not fully disclosing its own internal conflicts.

The 209 Times boss said paying him for political consulting work does not guarantee positive coverage from his site. He said only someone deemed “a worthy candidate” gets positive coverage, including those who have not hired him.

Politicians paying Sanchez aren’t the only subjects that have avoided salvos from the 209 Times.

Since Sanchez took his school district job, his news site has published effusive accounts of the good deeds done by the Family Resource Centers that he heads. Last August, the outlet’s Facebook page told how Sanchez’s department passed out books to community members and informed citizens about rental assistance programs. The story bore the hashtag #209Strong.

In late June, 209 Times posted video of Sanchez touting his department’s giveaway of food and other essentials, noting how especially strapped residents were because of runaway inflation. Sanchez implied in an email that he deserves credit for the thousands of bags of groceries and other support provided.

Traditional journalism outlets prohibit employees from holding outside jobs or alliances that might present the reality, or the appearance, of a conflict of interest.

“When you are doing other things that take you beyond your journalistic mission then you are dividing your loyalties between your duty to citizens and your duty to whomever your other masters are,” said Mark Ludwig, a Sacramento State journalism professor, who was commenting on general journalistic practices, not 209 Times specifically. “You run into the potential of affecting your credibility as a journalist.”

Sanchez has little time for such guidelines. He’s too busy expanding his brand.

He has launched sites in Sacramento and Los Angeles, and wants to make sure there’s no doubt who deserves credit. In one post, he declared that 209 Times “has really revolutionized and crowdsourced news and information in a way that ... has not been seen before in the whole country.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.