A San Diego area school district was given LGBTQ-affirming kids’ books. Then parents objected

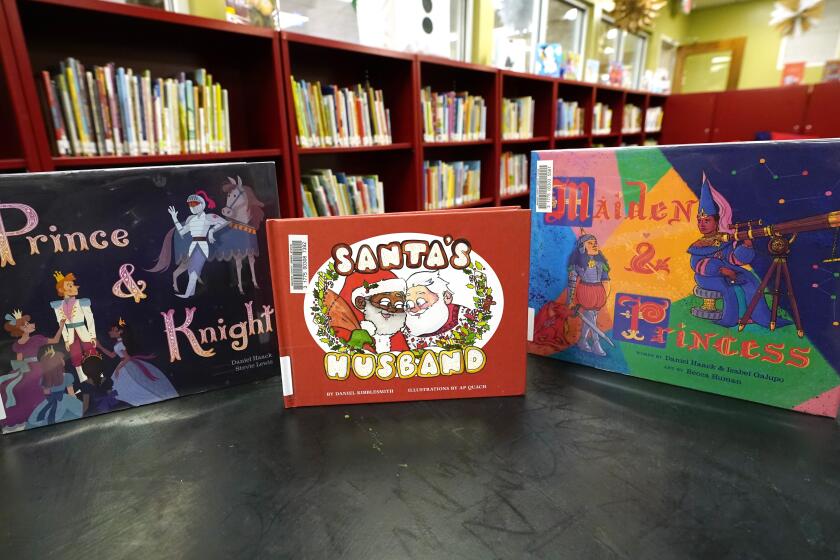

SAN DIEGO — One picture book tells the story of a boy who gets teased at school for wanting to wear jewelry and nail polish, but finds acceptance from his family. Another is about a crayon labeled as red that is really blue.

Over the last three years, Orange County native Keiko Feldman has helped donate and hand-deliver more than 15,000 LGBTQ-affirming children’s books to more than 1,000 public school libraries, mostly in California.

The idea is to show children from a young age that it’s OK to be LGBTQ, said Feldman, a documentary producer who is mom to one transgender child and one gay child and who co-founded the nonprofit Open Books.

“We want the world to be the kind of place where our kids are not evaluated on any of those criteria,” Feldman said. “I want the next generation of parents whose kids come out to them to not immediately feel like, ‘Oh God, how am I going to protect my kids from this world?’”

Get our top headlines every weekday morning

We'll deliver top news — local, sports, business and entertainment — and opinion straight to your inbox.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

School districts in liberal-leaning California have generally welcomed the books, according to Feldman. Two months ago, state Superintendent Tony Thurmond touted them at an event in the Bay Area. Feldman says she now has a waiting list of 70 public schools, half of them in San Diego County, whose leaders want the books in their libraries.

But when Feldman dropped off books last year in Solana Beach — a north county district of 2,800 students in kindergarten through sixth grade — at a teacher’s request, that was when the books received a less-than-enthusiastic response, she said.

Some parents and community members learned of the donation via social media and complained to the district, arguing that the books were inappropriate for elementary school libraries and would infringe on their right to teach their own values to their children.

So the district halted the books from going into circulation.

The donated books have yet to make it to Solana Beach school library shelves. Trained teachers are reviewing the books one by one to decide whether to put them into general circulation, and the review should conclude by early September, said Superintendent Jodee Brentlinger.

The Solana Beach School District is just one of many school systems nationwide that have become caught in politicized fights over the inclusion of books about gender, sexuality and race in libraries.

Lawmakers around the country have proposed book bans. Librarians have been attacked online and accused of indoctrinating kids. Attempts to get books removed from libraries are at their highest in decades.

A Mississippi library is on track to receive its full budget, months after a mayor threatened to withhold money because the library displayed LGBTQ books for young readers

Schools and libraries received at least 730 reported challenges to about 1,600 books last year, most of them books about LGBTQ or Black people, according to the American Library Assn. That’s the highest number in any one year since the association began tracking book challenges two decades ago.

There are likely more challenges that are going unreported, said Kathy Lester, president of the American Assn. of School Librarians. She also worries about what she calls “silent censorship,” as librarians decline to add controversial books for fear of losing their jobs or facing personal attacks.

“I want students to have access to materials and the freedom to read,” Lester said. “A choice.”

In Solana Beach, following the complaints about LGBTQ-affirming books, district leaders adopted a policy that allows parents to restrict their own children’s access to certain books, as well as to challenge a book’s inclusion in school libraries entirely.

The policy outlines a procedure for when parents, community members or school staff ask the district to ban a book for all students.

At that point, the district would ask the complainant to fill out a form, detail their concern, say whether they have read the entire book in question and sign their name. Then three committees of teachers, district leaders and others would convene to review the challenged book before deciding whether it should remain on library shelves.

Sign up for our weekly Watchdog newsletter

Get investigative reporting and data journalism from San Diego County and beyond.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

In the past, Brentlinger said, Solana Beach parents have submitted requests to restrict their own kids from reading books involving subjects like witchcraft, including Harry Potter books, or “potty language,” including the Captain Underpants graphic novel series. She could not say how many requests the district has received in the past.

“Whenever we are able to provide our students or our staff or our families with choices, we want to be able to support that,” Brentlinger said.

Solana Beach teachers and staff designed the new policy using guidelines from the American Library Assn., which recommends that libraries adopt formal, consistent and transparent procedures and criteria for reconsidering books after receiving a complaint.

Under the policy, specially trained Solana Beach teachers decide which books go in libraries and are required to choose books that represent the experience of all groups of people, including people of different racial and ethnic groups, religions, abilities and people across the gender spectrum.

The district policy also designates a so-called “professional bookshelf” in each library for books on sensitive topics — such as human anatomy, divorce, terminal disease and death — that require parental consent for use with students, Brentlinger said. Trained teachers decide what goes on these bookshelves.

None of the donated LGBTQ-affirming books has yet been slated for that shelf, Brentlinger added.

Some parents have hailed Solana Beach’s school library policy for letting them decide what their kids can and can’t read.

That includes Dana Furman, a mother of three, including one fourth-grader who recently attended Solana Vista Elementary School. She had complained to the district last year, objecting to the LGBTQ-affirming books’ presence in public schools and saying they promoted a far-left political agenda.

“I think that is damaging to children. I think it is experimental. I think it’s going to cause a lot of confusion and problems with identity,” said Furman, who is now moving her family to Arizona, saying she thinks California’s public schools have become too political.

“The school district needs to do all they can to keep politics out of education, and the best way to do that, since you can’t make everybody happy, is parent choice.”

Other parents worry that letting parents restrict access to LGBTQ-affirming books could cost vulnerable students a needed source of representation and validation. They also say the books’ opponents are misunderstanding and overreacting.

“Preventing these conversations makes it a bigger deal than it needs to be. You could easily just include it in the way we teach the existence of boys and girls,” said Marina Fleming, whose nonbinary child attended sixth grade in Solana Beach last school year. “How does talking about how some kids don’t ascribe to the male-female binary hurt anyone?”

Fleming takes issue with the fact that the district’s policy lets parents curb their children’s access to books at school — the only place some children might be exposed to LGBTQ-positive books if their parents aren’t tolerant at home.

Lester said she thinks it’s fine for parents to tell a school librarian that they don’t want their child to view some materials, as long as it doesn’t affect other students’ access.

But Fleming worries that if one parent asks to opt their child out of a book used in a classroom, it could prevent a teacher from using the book for the rest of the class.

“Allowing parents to police what their kids have access to is a slippery slope,” she said. “Their intent may not be to restrict access to books, but I believe the impact will be such.”

Although critics often characterize LGBTQ-affirming children’s books as being about sex, Feldman said the books her nonprofit donates are no more about sex than traditional children’s fairy tales are.

“You have kids’ books in the library about princes and princesses and all kinds of love stories, and we don’t consider that sexual,” Feldman said.

Contrary to what some parents fear, reading about gay or transgender people will not make children gay or transgender, she added. The stories are meant to help kids understand and accept themselves and other LGBTQ people.

LGBTQ youth of faith across the United States are sharing their stories during Pride Month

Understanding and acceptance are critical, she said, as LGBTQ youth are far more likely to suffer from low self-esteem, depression and anxiety.

About three-quarters of gay, lesbian or bisexual youth have reported feeling sad or hopeless almost every day for weeks in a row, compared with 37% of heterosexual youth, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Transgender and nonbinary youth are twice as likely as cisgender LGBTQ youth to report depression, suicidal thoughts and suicide attempts.

Brentlinger says the district is meanwhile taking other steps to support LGBTQ students.

In June, the school board unanimously approved a three-year, $19,500 contract with local nonprofit TransFamily Support Services to train staff and board members on how to support LGBTQ students and educate parents about gender diversity.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.