Hate getting to LAX? In an alternate reality, you could be catching flights in Palmdale

Last year, we began asking readers to send us their pressing questions about Los Angeles and California.

Every few weeks, we put the questions to a vote, asking readers to decide which question we should answer in story form.

This question, suggested by a source quoted in a previous story, won our latest reader poll: Why is LAX far from the center of L.A.?

—

“True friendship is knowing that your friends would pick you up from LAX, but you care about them too much to ask for that ride.”

This spot-on piece of wisdom from popular Instagram account Overheard LA points to a truth known by many Angelenos: Getting to and from Los Angeles International Airport can be a major headache.

Angelenos aren’t alone — after all, it’s common for airports around the world to be situated far from downtown areas.

Traveling to LAX can easily take 45 minutes from downtown L.A., an hour from Hollywood, and far longer if you’re traveling from the Valley or Orange County. Then, there’s often bumper-to-bumper gridlock to endure once you arrive. And, as one Times reader noted a few years ago, “the LAX FlyAway bus from Union Station is great for getting to the airport, but coming home is another matter.”

Today’s travelers might take LAX’s location for granted. But it wasn’t inevitable that Los Angeles’ premiere airport — among the top five busiest in the world — would end up situated in the Westchester area, just a few minutes’ drive from the Pacific Ocean.

Its location shaped the trajectory of neighboring communities and the L.A. region as a whole. El Segundo was an oil town first, said Peter Westwick, an adjunct history professor at USC and director of the Aerospace History Project. “But then it shifted and became an aerospace center, in part because of LAX being there.”

Taxi fares don’t change. The FlyAway bus between the airport and downtown is under $10. And surely you have a friend who’s willing to pick you up.

LAX also helped transform places like Venice and Santa Monica into the tourism centers they are today. “When you’re arriving into L.A., it’s magical that you’re right on the beach. I think it did help the tourism of the Westside,” said Jean-Christophe Dick, vice president of the Flight Path Museum. “People want to be close to the airport.”

What if L.A.’s main airport had been developed elsewhere? For a brief moment, let’s step into the multiverse of California air travel. Hypothetically speaking — if history had played out differently — today’s travelers might fly out of some modern evolution of Vail Field (a former airfield in Montebello) or even travel to a so-called “superport” in Palmdale via high-speed train to catch flights on supersonic, intercontinental jetliners (yes, really).

We’ll get to those possibilities in a moment, but now, hopping out of the multiverse and back to the early days of air travel in Los Angeles, let’s find out why LAX was built on the site of an out-of-the-way barley field near the coast.

In the 1920s, air travel was a rare privilege, though it wasn’t exactly glamorous. “It was a little more hair-raising back in the day,” said Dick. “You’d be flying a lower altitude than you are today, which means that if there was weather, you’d feel it in a small plane.”

“Aircraft weren’t as reliable,” Dick continued, “and safety standards weren’t what they are today.”

However, the risks and discomfort of air travel didn’t dampen excitement around the flashy mode of transportation.

Many in Los Angeles saw airplanes as a “symbol of the technological future,” said Westwick. “There were all these airfields springing up all over the L.A. Basin... By 1929, there are over 50 airfields within 30 miles of downtown.” (Some of these airfields would later be transformed into golf courses.)

There’s more than meets the eye at Los Angeles International Airport.

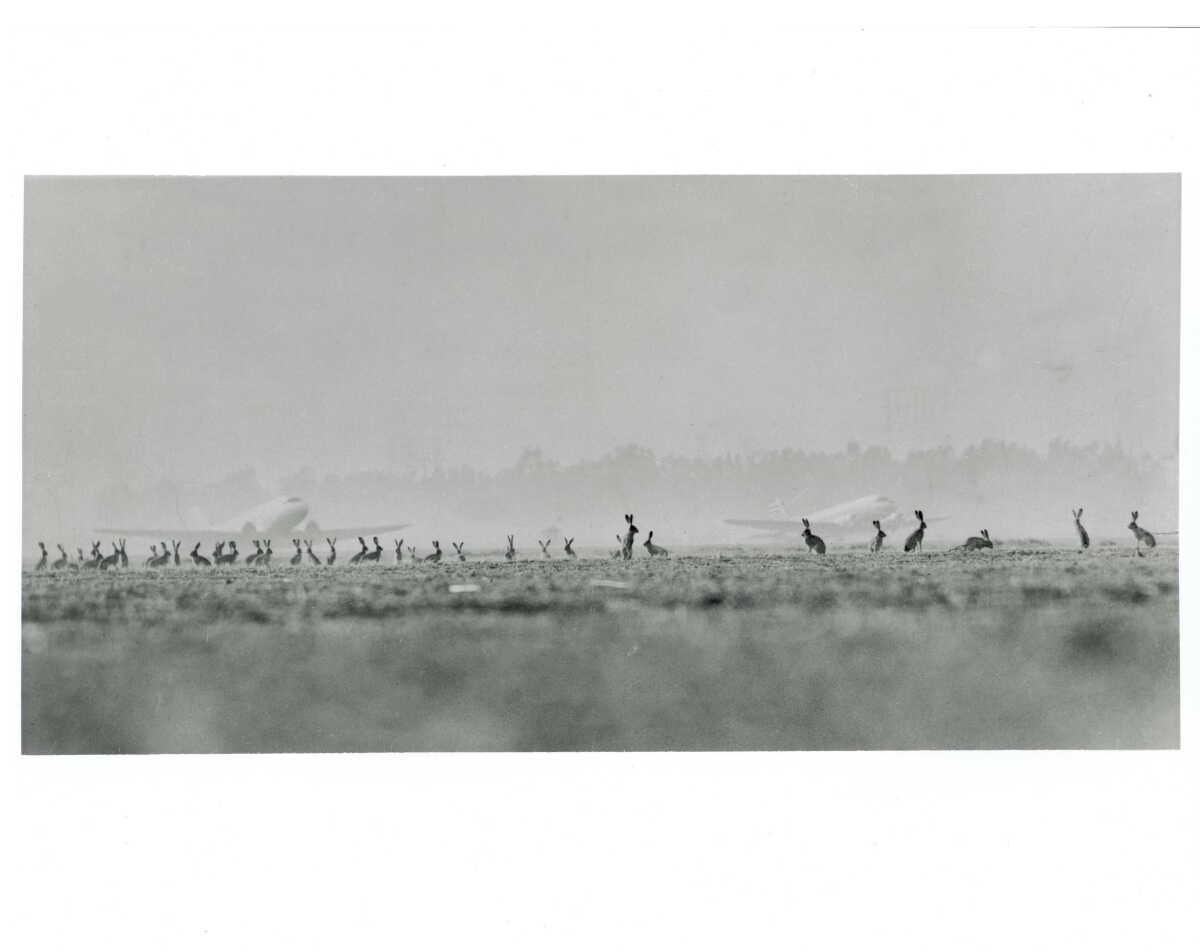

The danger of flight was one of the reasons why airfields were kept somewhat distant from developed areas — places like the area around then-relatively rural Westchester. “[Planes] crashed all the time, and you don’t want airplanes stalling and crashing in some neighborhood full of houses or businesses,” Westwick said. “Also, airfields were noisy and dusty.”

Another interesting fact, courtesy of Westwick: All of these decentralized, far-flung airfields around the city are one of the factors behind L.A.’s suburban sprawl. “Industry follows the airfields and real estate developers follow the industry,” he said. “That’s [one of the reasons why] you get these satellite cities scattered around LA.”

By the late 1920s, the search for a suitable site to build a municipal airport was in full swing.

The pressure was on. On April 3, 1927, the pages of The Times read: “While Los Angeles sleeps other Coast cities are providing themselves with municipal airports to be employed in profitable transcontinental air commerce that is not far distant.”

Celebrity aviator Charles Lindbergh, fresh off his flight across the Atlantic and years away from a public reckoning over his racist and anti-Semitic statements, gave a speech at the Coliseum in September 1927 on the future of air travel. “If you expect to keep your city on the air map, it will be necessary to construct a municipal airport,” he declared.

Two months earlier, a real estate agent named William W. Mines had offered 640 acres of what was called the Bennett Rancho in the Inglewood area for the City of Los Angeles to use as an airport.

This site, which came to be known as Mines Field, was ultimately chosen as the location for Los Angeles’ airport – becoming the predecessor of today’s Los Angeles International Airport.

But why was Mines Field chosen over other airfields in Los Angeles?

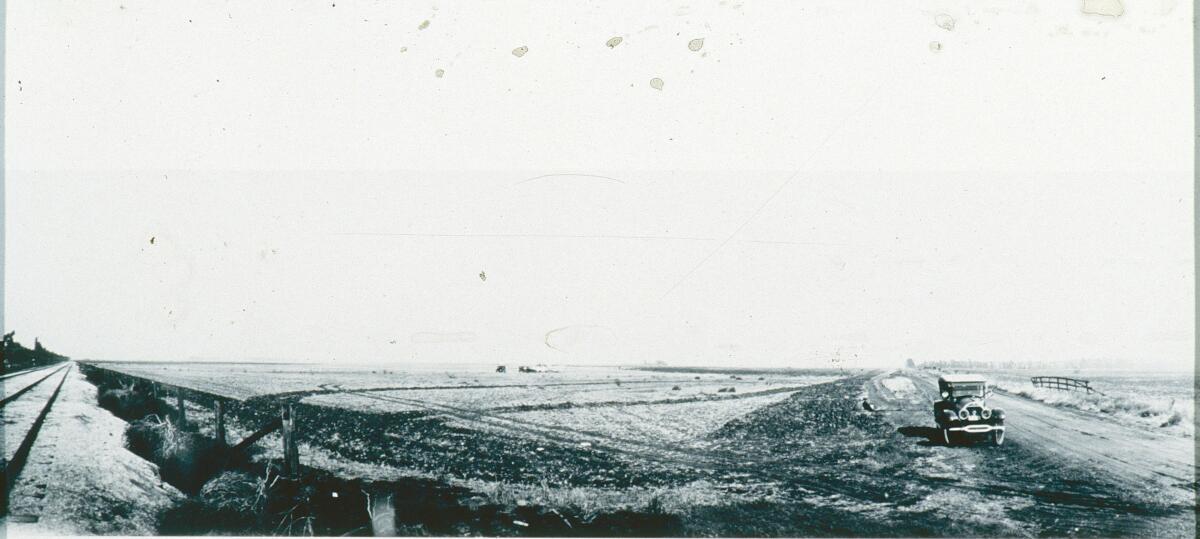

For one, it was cheap land, previously used for growing beans and barley, Westwick said.

Plus, the city needed a large, open area for the airport, an advantage held by Mines Field. It was “pretty much a blank slate,” Dick said, which meant the airport had room to grow over time.

Excitement over Mines Field was bolstered when the airfield was picked as the site for the ultra-popular 1928 National Air Races, which attracted “crowds of a couple hundred thousand over the course of this event,” Westwick said.

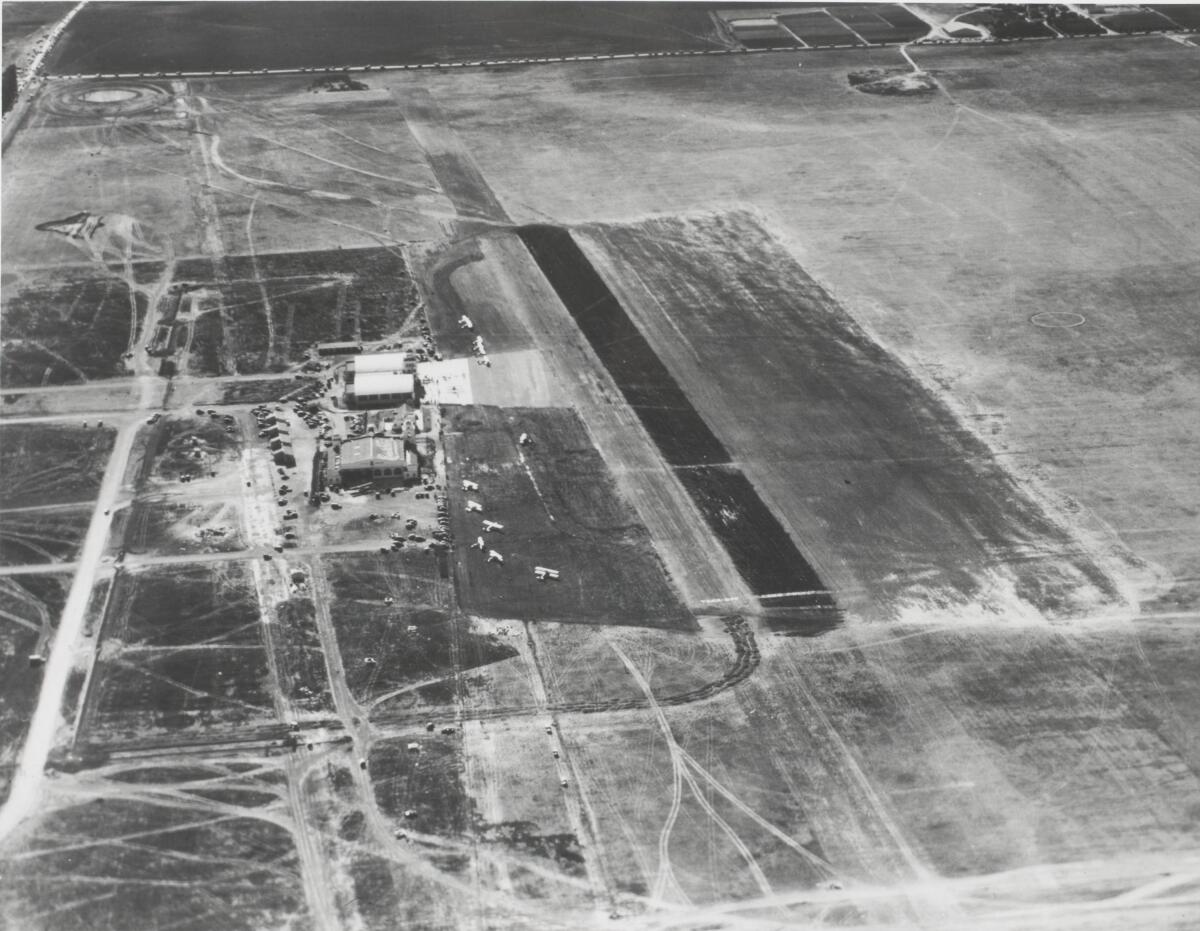

Los Angeles Municipal Airport, located on the site of Mines Field, began operation in October 1928. However, it took the better part of two decades before Mines Field’s destiny was sealed, Westwick said.

It wasn’t until 1937 that the City of Los Angeles officially committed to purchasing Mines Field. “L.A. makes a huge commitment to invest all this money to completely modernize L.A. Airport,” Westwick said.

A reader asked why L.A.’s recognizable skyline — with skyscrapers such as the Wilshire Grand Center and U.S. Bank tower — developed roughly 15 miles from the Pacific. We have answers.

“The commitment involved issuing bonds to cover the cost of the upgrades — i.e. the City of L.A. took a gamble. There was no guarantee the airlines would jump over to the L.A. Airport,” he said via email. But in the 1940s, after World War II, “airlines rewarded that civic investment by jumping over and committing to operate out of the L.A. Airport.”

“That is what turns Mines Field into LAX and makes LAX the central hub” for commercial travelers today, Westwick said, as opposed to Grand Central Air Terminal in Glendale (Los Angeles’ first commercial airport) or another airport.

Fast forward a decade or two for one last colorful wrinkle in aviation history — the proposed “superport” in Palmdale.

In midcentury Los Angeles, there was a push for a new international airport to ease congestion around LAX. The Board of Airport Commissioners endorsed the idea of a Palmdale airport in 1968.

How would travelers get to Palmdale? Via high-speed rail that would whisk people from the L.A. Basin to the airport, of course. (In 1988, The Times reported that the Los Angeles Department of Airports had so far “poured more than $100 million into acquiring and maintaining 17,750 acres of desert” in the Palmdale area.)

That’s right — in an alternate reality of your life in Los Angeles, you could be going up to Palmdale instead of LAX for your next flight.

So what happened to the “superport” idea?

“Why the originally announced jetport was never built is a complicated tale involving money, the San Andreas fault, demographics, the airline business, a high-speed train and the U.S. Air Force,” wrote staff writer T. W. McGarry. (Plus, the altitude and temperatures of Palmdale posed difficulties for airliners, Westwick added.)

A Palmdale “superport.” The once-popular Grand Central airport in Glendale. Other airfields dotted across L.A. — all paths not taken in the development of L.A.‘s behemoth airport.

I’m curious — how would you like to see air travel in Los Angeles evolve over the next 100 years? Drop your thoughts, ideas and hopes into the comments.

Are you curious about some facet of life in Los Angeles? Do you have a pressing question about California? Let us know for the chance to have your query answered in story-form next.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.