Stubborn La Niña looks like it may stick around for a rare third year

A stubborn La Niña climate pattern in the tropical Pacific is likely to persist through the summer and may hang on into 2023, forecasters say.

La Niña has been implicated not only in the unrelenting drought in the U.S. Southwest, but also in drought and flooding in various parts of the world, including ongoing drought and famine in the Horn of Africa.

If La Niña persists into the fall and winter, it would be only the third time since 1950 that the climate pattern has continued for three consecutive winters in the Northern Hemisphere, the U.N. World Meteorological Organization said last week.

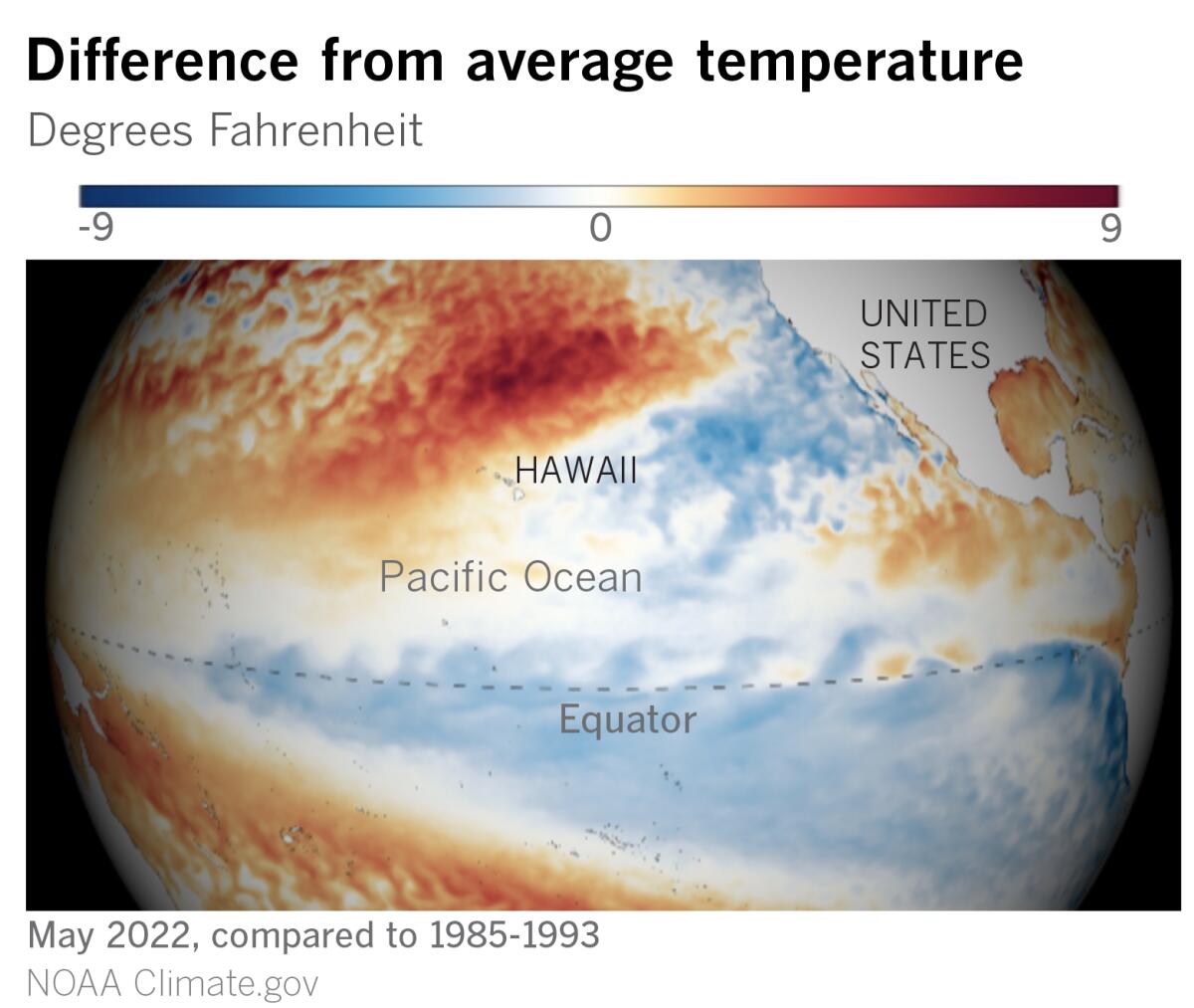

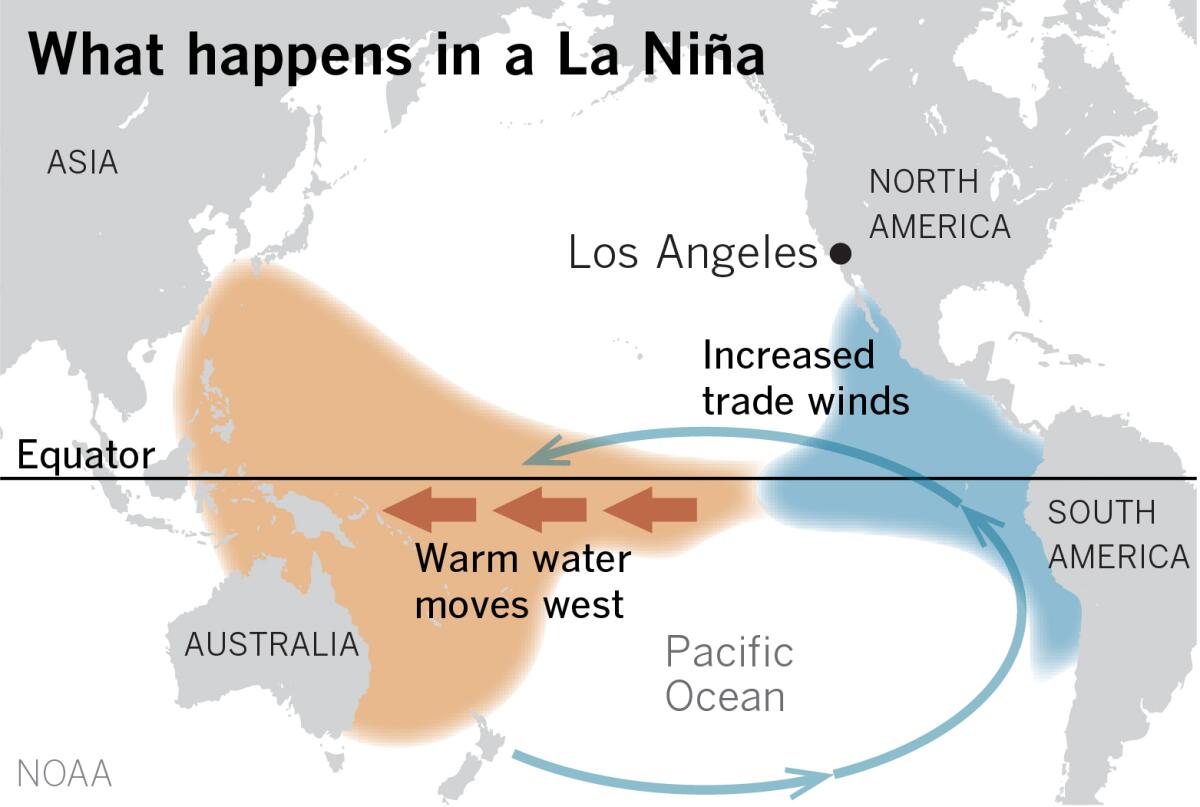

La Niña is the cooler sibling of El Niño, which, along with a neutral phase, constitutes the El Niño-Southern Oscillation. La Niña is a year-to-year or multiyear phenomenon characterized by cool sea surface temperatures in the equatorial central and eastern Pacific Ocean, coupled with altered global atmospheric circulation.

The update from the World Meteorological Organization echoed a U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration forecast last week that favors continuation of La Niña through the summer and into the winter. In its prediction for July to September, however, NOAA found that a continuing La Niña held only a fairly small edge — 52% to 46% — over a return to neutral ENSO territory. But it also said there was about a 59% chance of a return to La Niña by early winter.

In addition to the historic U.S. drought and the deadly drought in the Horn of Africa, drought in southern South America and above-average rainfall in Southeast Asia and Australia, New Zealand and surrounding islands have been blamed on La Niña.

In the U.S., La Niña is often associated with wetter conditions in the Northwest and drier conditions in the Southwest, Marty Ralph of UC San Diego’s Scripps Institution of Oceanography points out. A strong and highly unusual June atmospheric river, a mechanism that usually transports tropical moisture during the cooler rainy season, soaked Seattle and the Pacific Northwest a few days ago. The region around Yellowstone National Park suffered deluges and historic flooding this week. The Associated Press reported that Yellowstone got 2.5 inches of rain Saturday through Monday, and the Beartooth Mountains northeast of the park got as much as 4 inches. The U.S. Geological Survey reported record flow of 1½ times the previous 100-year record peak on the Clarks Fork tributary of the Yellowstone River in Montana.

Meanwhile, in the parched U.S. Southwest, hot, dry conditions led to extreme wildfire activity, including the Pipeline fire near Flagstaff, Ariz. Climate scientist Daniel Swain tweeted that the fire “visually resembles an erupting volcano.”

The unusually strong atmospheric river in the Pacific Northwest and the heat wave in the Southwest are definitely anomalies for mid-June, said Alex Tardy, a meteorologist with the National Weather Service in San Diego. As the atmospheric river weakened and sagged southward, it also brought thunderstorms to Northern California. But he cautions that he’s unsure it’s safe to blame this on a weak La Niña or climate change.

“I think it does relate to [an] overall east Pacific pattern that we’ve been stuck in for three years in Northern California and two in Southern California,” he said. For the second half of June, he predicts a continued battle between unusually cool and wet weather in the Pacific Northwest along an active jet stream and expanding high pressure in Texas and into the Southwest. There’s potential for heat to rebuild, especially in the deserts, he said. “This could be a very warm, much-above-average desert and mountain scenario, a lot like what we saw in 2021,” he said.

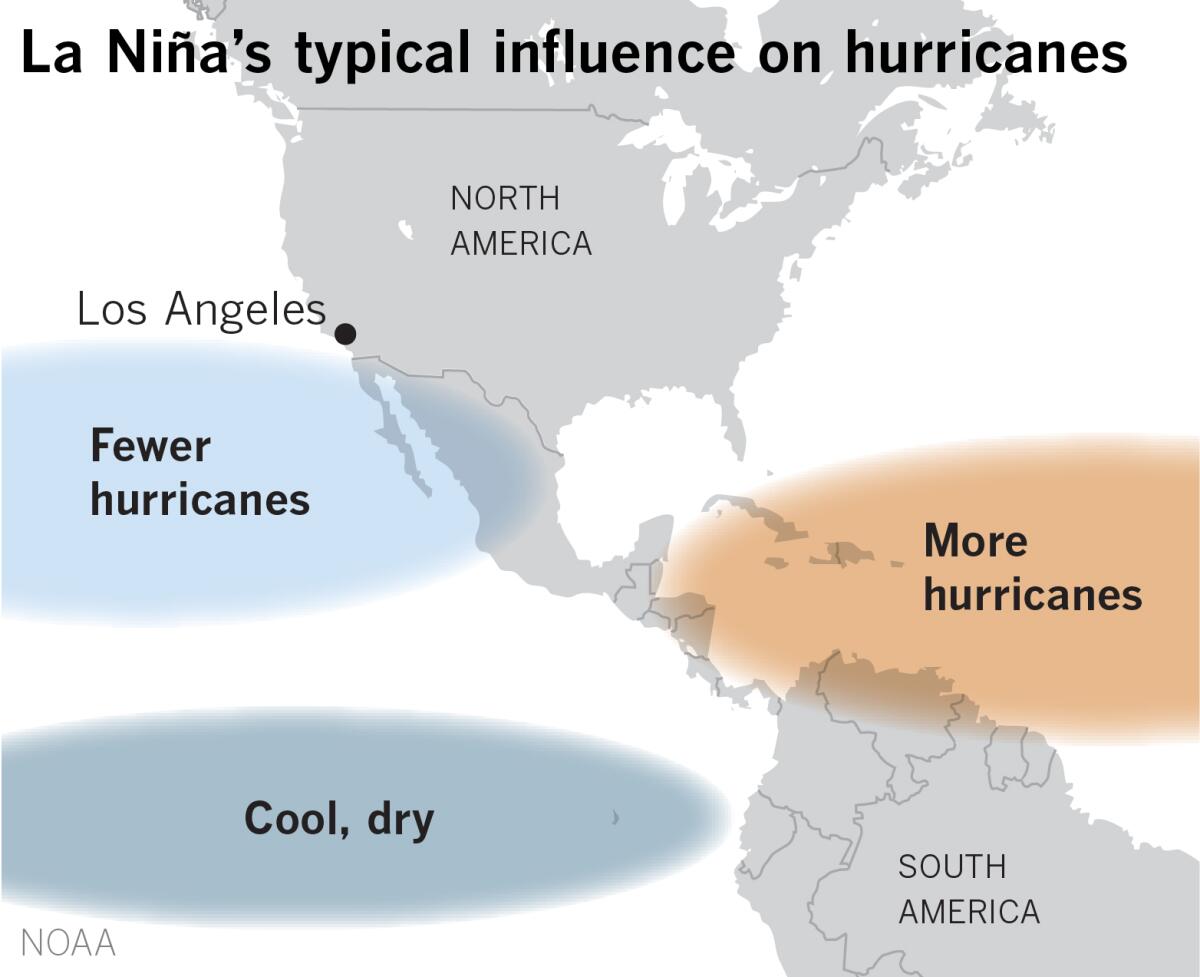

La Niña also affects hurricane seasons in the Atlantic and the Pacific. According to outlooks released by NOAA, there’s a 65% chance that the Atlantic hurricane season will be above average, with more and stronger storms. At he same time, there’s a 60% chance that the eastern Pacific’s season will be below average, according to NOAA.

This is because of atmospheric shear — the difference between wind speed or direction near the surface of the Earth and higher in the atmosphere. A big difference between low-level and high-level winds disrupts formation of hurricanes. This happens in the eastern Pacific because of La Niña, but in the main development region of the tropical Atlantic — a swath that stretches from about Mauritania and Senegal across to the Caribbean, where surface winds are mostly from the east — the upper-level westerlies are weaker, and hurricanes can build with less threat of vertical wind shear.

The U.S. Census Bureau estimates that at least 60 million Americans live in areas vulnerable to hurricanes, not counting residents who live farther inland and may be at risk for flooding due to heavy rain.

“These are La Niña impacts, but they’re exaggerated by climate change,” said climatologist Bill Patzert, formerly with NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, referring to droughts, deluges and hurricanes around the world. “There’s more going on here than your normal La Niña.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.