L.A. has a corruption problem. Can the next city controller fix that?

The FBI’s Los Angeles office has been extraordinarily busy at City Hall, launching probes into councilmembers, lobbyists, city lawyers, political aides and executives at the Department of Water and Power — some of whom have pleaded guilty.

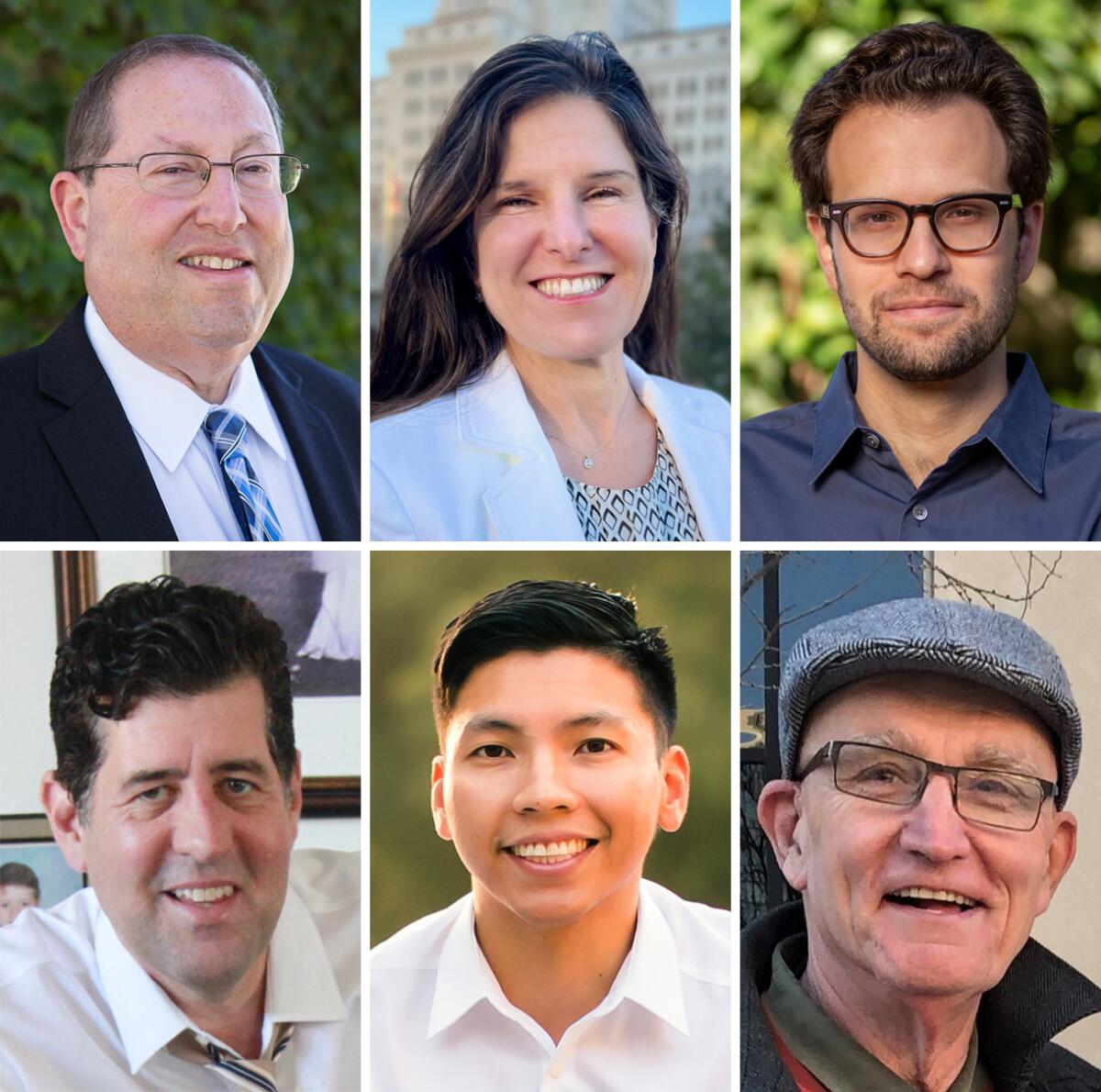

Now, voters in Tuesday’s election are set to choose a new city controller, a position that is itself something of a watchdog. The field of candidates has been confronting the question: Can the controller’s office, which performs audits and keeps an eye on the city’s books, also serve as a check on wrongdoing?

For the record:

3:31 p.m. June 4, 2022An earlier version of this article said candidate J. Carolan O’Gabhann has not spent any money on his campaign. He has spent less than $10,000.

Kenneth Mejia, one of the six candidates seeking the job, says he has already been doing that type of work, by shining a spotlight on city spending and alerting voters to improper campaign donations raised by one of his opponents, Councilman Paul Koretz.

Mejia, a 31-year-old accountant, took aim at Koretz earlier this year over a fundraiser the councilman held at the home of a DWP board member. City commissioners are barred under the city’s ethics ordinance from engaging in such activities. Koretz called the event “an inadvertent mistake” and promised to return about $8,000 from the event.

Caruso has changed his party registration four times in the last 11 years.

“The last thing City Hall insiders want is to be held accountable,” Mejia said in an emailed statement. “And that is what we did with our opponent, City Council member Paul Koretz.”

During the campaign, Mejia has explored the number of city workers who live out of state and explained the murky world of campaign slate mailers, which feature candidates — including Koretz — who have paid to appear on them.

In charts and graphics, on social media and oversized billboards, Mejia has also shown how much of the city budget is consumed by the LAPD — about 30%, more than any other city agency.

Mejia said he wants to divest from the LAPD, putting money instead into services that “actually keep people safe,” such as housing and mental health programs. A year ago, he urged council members to cut the LAPD budget and beef up spending on a new guaranteed income program, which has been providing $1,000 per month to impoverished households.

“Look at [police] pensions. Look at the new helicopter they’re getting for $7 million. Look at all the expenses for buildings and ammunition — basically everything,” Mejia told the council’s budget committee at the time. “Look at the LAPD budget and reduce that.”

Koretz, a resident of Beverly Grove, has taken a different approach, arguing that the LAPD needs both more officers and more civilian employees to address robberies and other crimes. He also pointed to Mejia’s statements in support of the People’s Budget LA, a coalition of grassroots groups that issued a report saying Angelenos want an 89% decrease in police spending.

The report, prepared as part of an extensive survey, said the greatest share of the budget should go toward “universal needs,” such as healthcare and mental health, leaving only a small fraction for law enforcement.

“The theory is that if you give money to everything else, you’ll solve all of society’s problems and you won’t have crime, and I think that’s an absurdly utopian notion,” Koretz said. “The idea that rapists would no longer rape and murderers would no longer murder is absurd.”

Mejia, in a lengthy Twitter thread, accused Koretz of “fear mongering,” saying the People’s Budget is a survey of priorities, not a “budget allocation pie chart.” He said the priorities spelled out in the report would in fact tackle the root causes of crime.

“The People’s Budget LA is not some made-up list of priorities,” Mejia wrote. “It’s what hard-working Angelenos demand!”

Koretz, Mejia and the other four candidates are running to succeed City Controller Ron Galperin, who carved out a reputation making data about city government more publicly accessible. Galperin was not nearly as confrontational as one of his predecessors, former City Controller Laura Chick.

Mejia, who has protested outside the homes of the city’s elected officials, would almost certainly pursue a more adversarial approach. Koretz, on the other hand, is expected to be a non-combative presence.

Koretz, 67, said he has quietly sought ways to make the city more efficient, shaving millions of dollars off a DWP proposal for sealing a reservoir in his Westside district. He said he has focused on paying down the LAPD’s bank of unpaid overtime hours — an effort that backslid in a huge way during the pandemic.

On corruption, Koretz said he would increase the size of the controller’s fraud, waste and abuse unit and welcome the FBI into City Hall to conduct stings.

The latter idea has drawn jeers from some of Koretz’s other opponents, who say federal agents needed no invitation to launch investigations of councilmembers, DWP executives and a onetime deputy mayor.

“That’s just Paul Koretz once again admitting he has no clue what’s going on,” said David Vahedi, an attorney who lives in Westside Village and is also running.

Vahedi, who lost to Koretz in a 2009 council race, said city leaders should have detected some of the questionable decisions at the heart of the federal DWP probe. Chief among them: the vote by the DWP board to award a $30-million contract for cybersecurity services without competitive bidding.

“What a controller should ask is, why are we doing a no-bid contract when there are thousands of companies with cybersecurity expertise?” said Vahedi, who worked at one point as an auditor for the state’s Board of Equalization.

Former DWP general manager David Wright pleaded guilty earlier this year to a bribery charge stemming from that DWP contract, admitting he had been offered a job with a $1-million yearly salary in exchange for the contract’s approval.

Vahedi, 55, said that if elected, he would seek extra review for any no-bid contract that exceeds $500,000. And he said the controller’s office should develop a relationship with the district attorney’s office, which investigates public corruption.

The issue of contracting is also high on the agenda for Stephanie Clements, who acts as the chief financial officer for the city’s Bureau of Street Services. Clements said that if elected, she would conduct a review of every no-bid contract awarded over the past five years.

Clements, 51, promised to help streamline the city’s competitive bidding process, which can take up to 24 months to carry out — wasting time and money. If the process were less burdensome, she said, city bureaucrats would not be nearly as tempted to avoid competitive bidding.

“That’s what differentiates me from all the other candidates,” she said. “I’ve worked in this bureaucracy trying to get things done. I know where the waste is, where the pain points are.”

Candidate Kenneth Mejia says his deleted tweets from 2020 are a “non-story.” As June 7 nears, his opponents are attacking him over his political messaging.

Clements said she would also use the office as a platform to inform the public about the connection between the salaries and benefits provided to city workers and campaign contributions made by their employee unions — a relationship she characterized as “legal corruption.”

A longtime resident of West Los Angeles, Clements dismissed Koretz as a “career politician” and argued that Mejia lacks the management experience to be controller.

Yet another candidate is Reid Lidow, a former aide to Mayor Eric Garcetti, who is campaigning on the idea of creating an office of transparency and accountability. Such an office would be charged with making information on city spending, and city decisions, more accessible to the public, he said.

Lidow, who lives in Encino, said that as controller, he would use artificial intelligence software to root out troubling patterns in government spending, establishing a “first line of defense” on waste and fraud. But he also warned that there are limits to what an auditor can do if a politician is determined to break the law.

“If a councilman wants to go to Las Vegas and take a kickback in poker chips, the controller has no way to stop that,” he said. “But what we can do is put in additional layers of review and security to discourage bad behavior, to advocate for ramped up penalties, and catch fraud as it happens.”

Get the lowdown on L.A. politics

Sign up for our L.A. City Hall newsletter to get weekly insights, scoops and analysis.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Lidow, 30, joined Garcetti’s office in 2017, writing many of the remarks the mayor made during his televised briefings on COVID-19. He was eventually promoted to executive officer, accompanying the mayor in and outside City Hall.

Also in the race is J. Carolan O’Gabhann, a schoolteacher who has spent less than $10,000 on his campaign. His strategies for fighting corruption include the creation of a commission to rewrite the City Charter and a recommendation to expand the council to 100 members, up from 15.

With a larger legislative body, council members would “watch over each other for any shenanigans” he said in an email.

The ballot also lists Rob Wilcox, an aide to City Atty. Mike Feuer who recently dropped out of the race and endorsed Koretz. He criticized Mejia for calling President Biden a racist and a rapist two years ago on Twitter, calling such behavior “shameful and unacceptable.”

Mejia deleted the Biden posts, which became an issue when he sought the endorsement of Democratic Party clubs. In a response to Wilcox, Mejia said he remains focused on running an inclusive, grassroots campaign that informs Angelenos about city spending.

“We always expected that City Hall insiders in this race would join forces against us,” he said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.