The ‘Dead Kid Club’: Parents of mass shooting victims are a growing network

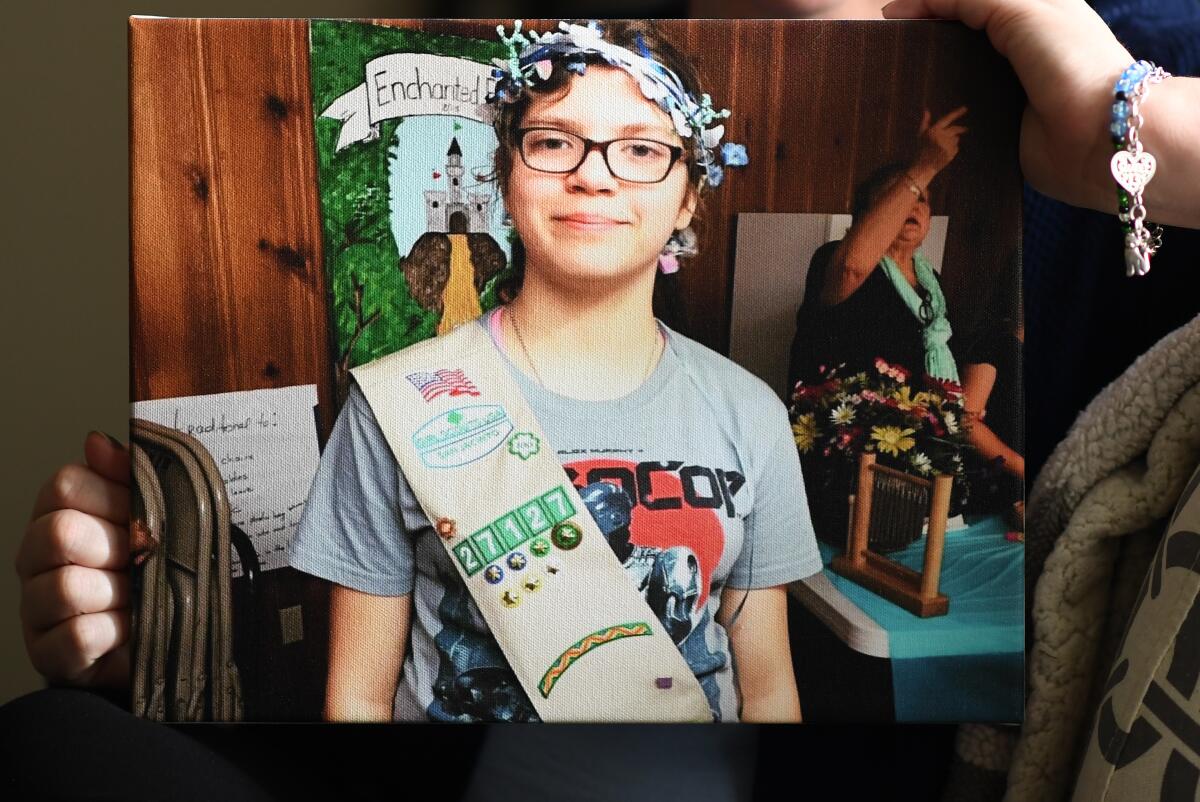

Four years and six days before a fourth-grade class was gunned down at Robb Elementary School in Uvalde, Texas, Rhonda Hart lost her teenage daughter, Kimberly Vaughan, in a shooting at a high school about 300 miles east.

She’s a member of a tragic, steadily growing network: parents of children who were killed in mass shootings. “We call it, unofficially, the Dead Kid Club,” she said.

So when she heard the news of yet another school shooting in Texas, Hart knew better than most what that will mean for the 19 families now missing young members.

“If you look up the cycle of grief, it’s supposed to go around in a circle: denial, anger, whatever. But that circle is B.S.,” she said. “It’s not so much a circle as a pinball machine. They’re going to be bouncing around from all these different emotions. They’re going to think they’re fine, and then one little incident will set them off.”

For Hart, one such incident came when she pulled up at the grocery store less than a year after her daughter’s death at Santa Fe High School. Kimberly, age 14, was one of eight students and two teachers shot to death; 13 others were wounded.

As she parked her car in the lot, Hart saw Girl Scouts selling cookies.

“I wasn’t emotionally prepared to see that, because my daughter and I sold Girl Scout cookies for 10 years. I cried so hard on the way home I almost had to stop and throw up,” she said.

Ever since, she’s preferred getting groceries delivered.

What was once a “floodgate” of grief is now typically just “a trickle.” Though it may be hard to believe at first, “it does get better,” Hart said.

“At some point, it dries up; it gets easier to deal with,” she said. But “you’re always going to have that little trickle of water; you’re always going to have that grief with you.”

::

That gradual ebbing of grief is not a universal experience among parents and other loved ones of mass shooting victims.

For some, grief hits hardest at the outset and slowly fades over time. For others, grief may take months to kick in, or linger for years, soul-crushing and destructive.

In the most extreme cases, parents who are overwhelmed by the pain take their own lives weeks, months or even years later, as Jeremy Richman did in 2019. His 6-year-old daughter, Avielle, was killed in the 2012 Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting, along with 19 other children and six staff members.

In Uvalde, the husband of one teacher killed in the May 24 shooting died of a heart attack “due to grief,” in the words of the couple’s nephew, John Martinez. “EXTREMELY heartbreaking and come with deep sorrow to say that my Tia Irma’s husband Joe Garcia has passed away due to grief,” Martinez wrote on Twitter. Irma Garcia was shot to death in her fourth-grade classroom, along with 19 children and one other teacher.

As Uvalde continues to reel from the violence, the funerals have begun. Amerie Jo Garza, age 10, who loved to swim and wanted to become an art teacher, was buried Tuesday in a closed casket ceremony.

As she walked to Amerie Jo’s rosary service Monday night, her aunt summed up the road ahead for the Uvalde families. “It’s been hard for my brother and his wife,” Desirae Garza, 33, said as she prepared to enter the funeral home. “Once all this is gone, we’ll still be grieving.”

The range of emotions immediately following a loved one’s death to gun violence can include “desolate sadness and hopelessness and helplessness and worthlessness that can also take the form of anger and blame and guilt,” said Dr. Gail Saltz, a psychiatrist and professor at New York Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell College of Medicine.

Life never fully went back to normal for Richard Martinez after his only child was shot to death in a 2014 mass killing rampage in Isla Vista, Calif. He can still quote how many days it’s been since Christopher Michaels-Martinez’s life was cut short at 20 years.

“It’s like you’re in a fog. It doesn’t seem real, and it takes a while for life to have any semblance of normality. It’s so unexpected, it’s so violent and it just completely changes your world,” he said.

Martinez said Christopher’s death “took me down to a place that I’ve never been before and there really are no words to describe.”

He feels fortunate that unlike some parents, he got to see his son live to be a young adult. But he still said he would “give up all the rest of my life for just five more minutes, just to talk to him.”

“The process is that you move on, your life moves on, and it’s always there,” Martinez said. “And I don’t want to forget, I don’t want to let go of it, I don’t want to forget Chris.”

People’s paths through grief diverge once the intensity of their initial feelings begins to wane. For the better part of a decade, Jaclyn Schildkraut has worked directly with families of children killed in shootings, including at Sandy Hook, interviewing more than 40 people who lost loved ones in mass shootings or survived mass shootings themselves.

The associate professor of criminal justice at the State University of New York at Oswego said the ways survivors move through their grief are “absolutely very different for everyone.”

“Some people are immediately in therapy, and some are years out and still not in therapy,” she said. “It really is a very individualistic process.”

Martinez’s path out of the darkest days of his grief was advocacy. But he said his work as a senior associate for the gun control and anti-gun-violence organization Everytown for Gun Safety has allowed him to channel his energies into something positive.

“You can stay in that hopelessness and helplessness, or you can reject that hopelessness and helplessness and you can act,” he said. “So, for me, self-care has been my advocacy. For me, it’s been the opportunity and the challenge of trying to make a difference because I can’t accept the way that my son died.”

Other people find some solace in hobbies, intellectual pursuits or a new career. Many find purpose in initiatives launched in their loved one’s honor.

On Friday, Hart honored her cat-loving daughter by attending a dedication ceremony for Kim’s Cat Haven at Bayou Animal Services, an animal shelter in Dickinson, Texas. It’s a room built to serve cats with feline immunodeficiency virus that’s been decorated in a “Harry Potter” theme; Kimberly was an avid fan of the fantasy series.

“It was Kimberly’s 16th birthday — the summer of 2019. People would say, ‘What can we do to honor Kimberly this year?’ And I said, ‘Why don’t you make donations to the shelter?’” Hart said. “It just grew into this thing.”

::

Keenon James’ brother, Sean, was shot to death in Maryland in 1993, before Columbine and Sandy Hook and Aurora and Uvalde. He said his personal network and local community played a crucial role during the difficult period immediately following his brother’s slaying, which remains unsolved.

Since then, James has taken his embrace of community a step further. He’s now the director of the Everytown Survivor Network, which connects people who have recently been affected by gun violence with others who have that shared experience.

That group is growing at a rapid clip. In 2020, gun-related incidents surpassed car crashes as the leading cause of death among young people ages 1 to 19, according to an analysis of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data.

“I’ve managed to refocus my energy and put it toward a solution, and that’s something very important to me and a lot of people that join our Everytown Survivor Network,” James said. “The survivor network provides that support.”

Ron Avi Astor, a professor of social welfare at UCLA who studies school violence, said families that have lost a loved one to gun violence have told him time and again that community was key.

“What was most important was the sense of community and everybody gathered ‘round,” he said. “The reason the community is so important is that’s who stays there after everyone is gone.”

Astor said that although money can help family members who want to start a foundation or dedicate something to a fallen loved one, he does not “think that wealth alone is the only factor in making a difference.”

“I’ve seen families from all income levels honor the memory of their loved ones who were murdered by becoming activists, lobbying for support or legislation that would prevent this from happening again, and initiating lawsuits,” he said.

For James, it’s also important that people understand it’s not just those injured by bullets, their loved ones, and the families of people who were killed who need help after a mass shooting. Like many experts and survivors, he emphasized the need for entire communities to receive support and treatment.

“One of the things we stress is it’s greater than just the families that are directly impacted,” he said. “The ripple effect of it — that’s what happens to our communities. And now we’re all going to have different levels of grief and trauma.”

The loss of a child in a shooting is also a wound that requires treatment. Sometimes that comes in the form of counseling. Sometimes it requires medication. Whatever the remedy, experts say it’s a necessary part of recovering from such a deeply traumatic event.

“Whether you call this complicated grief or post-traumatic stress disorder, or a mushing of the two, you kind of have to treat individual symptoms because that’s all we know how to do,” Saltz said. “That may have to do with psychotherapy, that may have to do with medication in some circumstances.”

For Hart, it’s a little bit of everything. She said she knew she needed help after the initial shock of her daughter’s death had begun to wear off. So she has embraced treatment in all its forms.

“It’s been a lot of therapy. It’s been medication support, better living through chemical intervention. I have an awesome service [dog], his name is Mario,” she said. “So, yeah, it’s been a lot of work.”

After a mass shooting, an estimated 28% of witnesses will develop PTSD, according to the National Center for PTSD. Many people who lose loved ones to gun violence develop depression, anxiety or other psychological conditions.

That’s where long-term psychotherapy, medication and other support comes in. Though the pain never fully subsides, with help, people “do get better and better,” said Charles Figley, a leading expert on disaster mental health and director of the Tulane University Traumatology Institute.

“More often than not, they’re able to work through it and get some answers, whether they’re satisfying or not,” he said. “Those answers are what helps build the scaffolding for a healing theory.”

::

After Rukiye Abdul-Mutakallim’s son was gunned down by strangers in Ohio in 2015, she embarked on a spiritual journey that led her to a place many would find unfathomable.

She ultimately forgave the teenagers who were accused of killing and robbing her son as he walked home from a store carrying food for his family in the low-income Cincinnati neighborhood where they lived.

The road began with many hours of praying and learning everything she could about how her son, Suliman, died. He was 39, a Navy veteran. Next, she found a way to overcome her own guilt.

“It begins not with forgiving the assailant but with forgiving yourself,” she said. “When you cut yourself with a knife, you don’t say, ‘Oh, this knife.’ You say, ‘How could I do this? I must have done something wrong.’ … I had to have the answer — ‘What part did I play?’”

Abdul-Mutakallim turned to what she calls the “innate laws” of humanity: “That we are one, we come from one single cell, we are of one family, we are the flower garden of mankind.”

From there, she said, she was able to find a place in her heart to forgive the people who hurt her son. She realized that they had not been born violent, that they had been harmed by other people in their lives and by the circumstances of their upbringings.

“As I saw two of the assailants in juvenile court … I looked at them and I saw them and I was shocked. They were babies, they were children,” she said.

“I didn’t say, ‘Why my son, why me, how could they do such a horrible thing?’ ... I didn’t say that. I said, ‘What happened to them?’”

She has since turned to advocacy, organizing protests and promoting love and healing through her nonprofit, the Musketeer Assn., which, she said, keeps going “in spite of the heartstring budget we have.”

Through forgiveness, prayer and advocacy work, Abdul-Mutakallim says she has been able to find some peace in the wake of tragedy.

“These are the things that settle the spirit and allow you to start healing,” she said. “And then you begin to rise above the trauma, but you don’t forget the trauma.”

Times Houston bureau chief Molly Hennessy-Fiske in Uvalde and staff writer Sean Greene in Los Angeles contributed to this story.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.