California families who lost loved ones to fentanyl-laced drugs press lawmakers to act

Life as he knew it ended for Matt Capelouto two days before Christmas in 2019, when he found his 20-year-old daughter, Alexandra, dead in her childhood bedroom in Temecula. Rage overtook grief when authorities ruled her death an accident.

The college sophomore, home for the holidays, had taken half a pill she bought from a dealer on Snapchat. It turned out to be fentanyl, the powerful synthetic opioid that helped drive drug overdose deaths in the U.S. to more than 100,000 last year.

“She was poisoned, and nothing was going to happen to the person who did it,” Capelouto said. “I couldn’t stand for that.”

The self-described political moderate said the experience made him cynical about California’s reluctance to impose harsh sentences for drug offenses.

So the suburban dad, who once devoted all his time to running his print shop and raising his four daughters, launched a group called Drug Induced Homicide and traveled from his home to Sacramento in April to lobby for legislation known as Alexandra’s Law. The bill would have made it easier for California prosecutors to convict the sellers of lethal drugs on homicide charges.

Capelouto’s organization is part of a nationwide movement of parents-turned-activists fighting the increasingly deadly drug crisis — and they are challenging California’s doctrine that drugs should be treated as a health problem rather than prosecuted by the criminal justice system. Modeled after Mothers Against Drunk Driving, which sparked a movement in the 1980s, organizations such as Victims of Illicit Drugs and the Alexander Neville Foundation seek to raise public awareness and influence drug policy. One group, Mothers Against Drug Deaths, pays homage to MADD by borrowing its acronym.

The groups press state lawmakers for stricter penalties for dealers and lobby technology companies to allow parents to monitor their kids’ communications on social media. They erect billboards blaming politicians for the drug crisis and stage “die-in” protests against open-air drug markets in Los Angeles’ Venice Beach and San Francisco’s Tenderloin neighborhood.

“This problem is going to be solved by the grass-roots efforts of affected families,” said Ed Ternan, who runs the Pasadena-based group Song for Charlie, which focuses on educating youths about the dangers of counterfeit pills.

Some prosecutors are pursuing murder charges for dealers linked to fentanyl deaths. But a public defender said such moves are outside the scope of the law.

Many parents mobilized after a wave of deaths that began in 2019. Often, they involved high school or college students who thought they were taking Oxycontin or Xanax purchased on social media but were actually ingesting pills containing fentanyl. The drug first hit the East Coast nearly a decade ago, largely through the heroin supply, but Mexican drug cartels have since introduced counterfeit pharmaceuticals laced with the highly addictive powder into California and Arizona to hook new customers.

In many cases, the overdose victims are straight-A students or star athletes from the suburbs, giving rise to an army of educated, engaged parents who are challenging the silence and stigma surrounding drug deaths.

Ternan knew almost nothing about fentanyl when his 22-year-old son, Charlie, died in his fraternity house bedroom at Santa Clara University a few weeks before he was scheduled to graduate in spring 2020. Relatives determined from messages on Charlie’s phone that he had intended to buy Percocet, a prescription painkiller he had taken after back surgery two years earlier. First responders said the strapping 6-foot-2-inch, 235-pound college senior died within a half-hour of swallowing the counterfeit pill.

Ternan discovered a string of similar deaths in other Silicon Valley communities. In 2021, 106 people died from fentanyl overdoses in Santa Clara County — up from 11 in 2018. The deaths have included a Stanford University sophomore and a 12-year-old girl in San Jose.

With the help of two executives at Google who lost sons to pills laced with fentanyl, Ternan convinced Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, YouTube, and other social media platforms to donate ad space to warnings about counterfeit drugs. Pressure from parent groups has also spurred Santa Monica-based Snapchat to deploy tools to detect drug sales and restrictions designed to make it harder for dealers to target minors.

Since the earliest days of the opioid epidemic, the families of people dealing with addiction and of those who have died from overdoses have supported one another in church basements and on online platforms from Florida to Oregon. Now, the family-run organizations that have sprung from California’s fentanyl crisis have begun cooperating with one another.

A network of parent groups and other activists that calls itself the California Peace Coalition was formed recently by Michael Shellenberger, a Berkeley author and activist running for governor as an independent.

One critic of California’s progressive policies is Jacqui Berlinn, a legal processing clerk in the East Bay who started Mothers Against Drug Deaths — a name she chose as an homage to the achievements of Mothers Against Drunk Driving founder Candace Lightner, a Fair Oaks homemaker whose 13-year-old daughter was killed in 1980 by a driver under the influence.

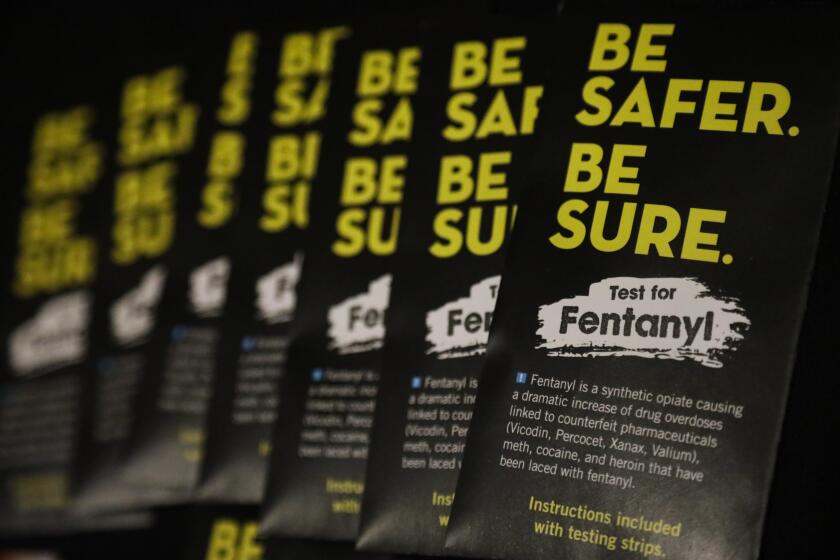

Fentanyl is often mixed with other drugs (including heroin, methamphetamine and cocaine) to increase potency, but it can be deadly. Test kits can help.

Berlinn’s son, Corey, 30, has used heroin and fentanyl for seven years on the streets of San Francisco. “My son isn’t trash,” Berlinn said. “He deserves to get his life back.”

She believes the city’s decision not to charge dealers has allowed open-air narcotics markets to flourish in certain neighborhoods and have enabled drug use, rather than encouraged people dealing with addiction to get help.

In April, Berlinn’s group spent $25,000 to erect a billboard in the upscale retail district of Union Square. Over a glowing night shot of the Golden Gate Bridge, the sign says: “Famous the world over for our brains, beauty and now dirt-cheap fentanyl.”

This month, the group installed a sign along Interstate 80 heading into Sacramento that targets Democratic Gov. Gavin Newsom. Playing off signage used at parks, the billboard features a “Welcome to Camp Fentanyl” greeting against a shot of a homeless encampment. The group said a mobile billboard will also circle the state Capitol for an undisclosed period.

Mothers Against Drug Deaths is calling for more options and funding for drug treatment and more arrests of dealers. The latter would mark a sharp turn from the gospel of “harm reduction,” a public health approach embraced by state and local officials that holds abstention as unrealistic. Instead, this strategy calls for helping people dealing with addiction stay safe through measures such as needle exchanges and naloxone, an overdose reversal drug that has saved thousands of lives.

The parent movement echoes recall efforts happening in two major cities. Progressive prosecutors Chesa Boudin in San Francisco and George Gascón in Los Angeles County have veered away from throwing street dealers in jail, which they call a pointless game of whack-a-mole that punishes poor people of color.

California lawmakers are wary of repeating the mistakes of the war-on-drugs era and have blocked a series of bills that would stiffen penalties for fentanyl sales. They say the legislation would accomplish little apart from packing the state’s jails and prisons.

“We can throw people in jail for a thousand years, and it won’t keep people from doing drugs, and it won’t keep them from dying,” said state Sen. Scott Wiener (D-San Francisco). “We know that from experience.”

Some parents agree. After watching her son cycle in and out of the criminal justice system on minor drug charges in the 1990s, Gretchen Burns Bergman became convinced that charging people with minor drug offenses, such as possession, is counterproductive.

In 1999, the San Diego fashion show producer started A New Path, which has advocated for marijuana legalization and an end to California’s “three strikes” law. A decade later, she formed Moms United to End the War on Drugs, a nationwide coalition. Today, both her sons have recovered from heroin addiction with the help of “compassionate support” and work as drug counselors, she said.

For years, this Canadian city has hosted safe consumption sites for addicts. They’ve saved lives, but with some painful tradeoffs.

“I’ve been at this long enough to see the pendulum swing,” Burns Bergman said of the public’s shifting views on law enforcement.

In December, Brandon McDowell, 22, of Riverside, was arrested and accused of selling the tablet that killed Capelouto’s daughter. McDowell was charged with distributing fentanyl resulting in death, which carries a mandatory minimum sentence of 20 years in federal prison.

Although Alexandra’s Law failed to make it out of committee, Capelouto pointed out that years of lobbying went into the passage of stricter drunk driving laws. He vowed not to give up on the bill named for his daughter, who wrote poetry and loved David Bowie.

“I’m going to be back in front of them,” he said, “every year.”

This article was produced by Kaiser Health News, one of the three major operating programs at the Kaiser Family Foundation.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.