Orange County father’s child custody case complicated by the war in Ukraine

In a video recently posted on social media, a Russian soldier in heavy body armor holds an American passport in his hands and says it belonged to an American mercenary killed in Ukraine.

The soldier says in the video posted earlier this month on the messaging app Telegram that the mercenary is buried in a settlement outside the city of Mariupol, which Russia claimed earlier this week to have captured in its ongoing war with its neighbor.

But Orange County resident Cesar Quintana said the passport belongs to him. The Russian journalist who posted the video also posted a closeup shot of the passport that shows Quintana’s face.

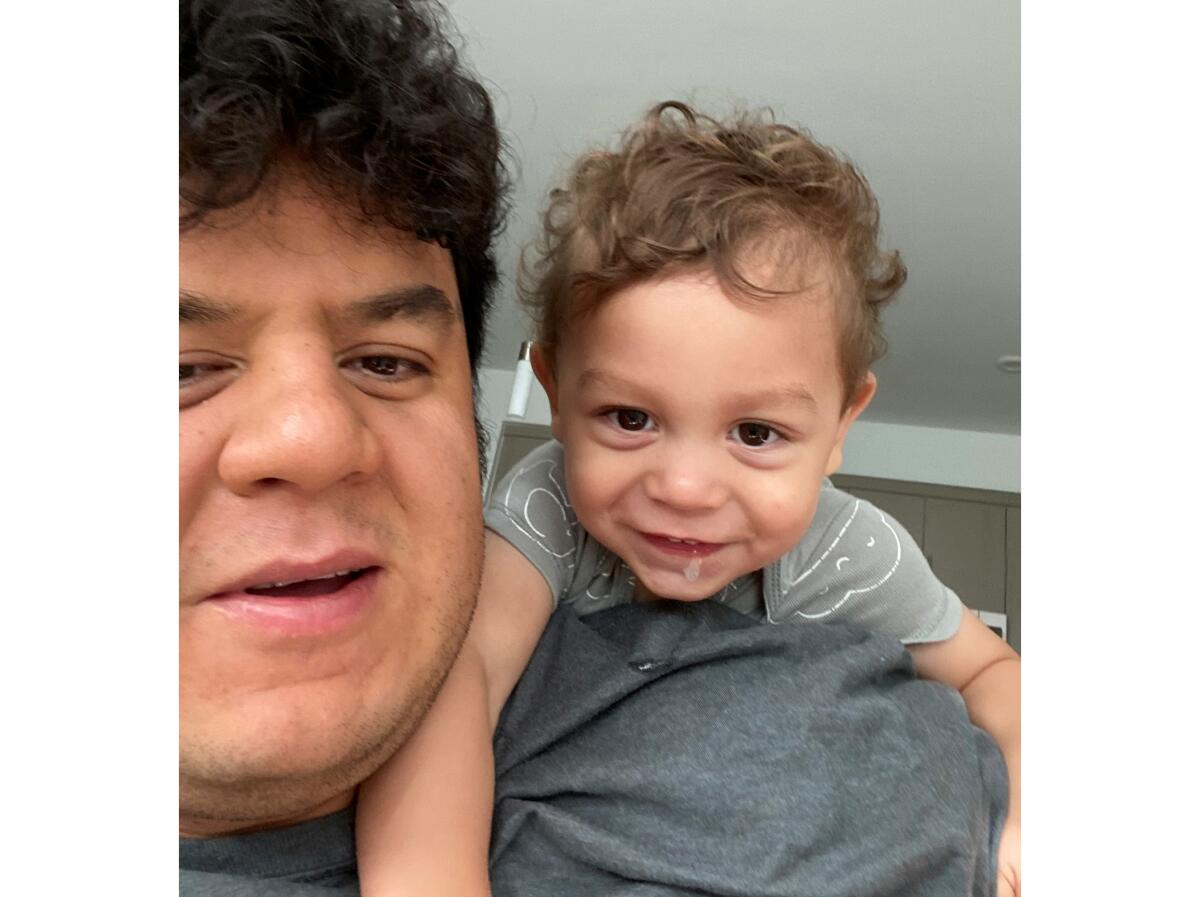

Quintana, 35, said the document was confiscated by Ukrainian authorities when he was in Mariupol last year attempting to regain custody of his 2-year-old son, Alexander, who was born in the U.S.

Quintana and his estranged wife, Antonina Aslanova, are engaged in an international child custody dispute, which has been made more complicated by the war.

“I know that passport,” Quintana said in a recent interview with The Times. “It was taken from me by the Mariupol police when I was in Ukraine trying to get my son out of the country.”

Quintana said he and his wife were separated when she visited him and their son at his Aliso Viejo apartment in December 2020. He said he was recovering from gall bladder surgery and when he fell asleep, his wife took their son and fled to her home country of Ukraine.

In a Sept. 8, 2021, letter to Ukrainian authorities, the Orange County district attorney’s office says that a judge had granted Quintana sole custody of Alexander because of his wife’s “alcohol abuses.” The district attorney subsequently filed a criminal complaint against Aslanova for child abduction.

Last fall, Quintana traveled to Mariupol where Aslanova and Alexander were staying with her parents. He said the couple attempted to give Alexander some semblance of normality with family outings in Ukraine.

Quintana’s mother, Florencia Gómez, wanted to see her grandson and also made the trip to Ukraine.

“I couldn’t wait to see my grandbaby again,” Gómez said. Her nickname for Alexander is “torito,” because he’s a Taurus. She left a short time later, thinking her son and Alexander would soon follow.

Meanwhile, tensions in the region escalated as Russian troops amassed at the border with Ukraine.

During his visit, Quintana said he attempted to flee Ukraine with Alexander. He said he had a court order from a California judge showing he had legal custody.

But Mariupol police were notified by Aslanova’s family that Quintana had abducted his son and did not have permission to leave the country, Quintana said.

“That’s when they took our passports,” he said. Quintana would have to wait to be issued a new passport, but in the meantime police threatened to detain him so he returned Alexander to his mother-in-law, he said.

Quintana went back to California but he said he promised himself he would return for his son.

A few months later, Russia invaded Ukraine. Since then, civilian casualties have mounted as the Russian army has pounded Mariupol and other eastern cities in the Donbas region. Quintana said he planned to return to Ukraine via Poland with an aid group in March to find Aslanova and Alexander.

But before he embarked on his trip, Quintana said the State Department informed him that his wife and child had fled to Russia.

Quintana said he hasn’t had a chance to speak with Aslanova recently, but that the two messaged each other once after she arrived in Russia. He said he is relieved that Alexander is no longer in Ukraine as the war rages on but worries about his future in Russia.

“To go from thinking if he’s in Ukraine, wondering if he’s alive, and then for him to be in Russia,” Quintana said. “It’s bittersweet news.”

Aslanova told the Washington Post she and Alexander spent the early days of the Russian invasion in a Mariupol basement before they decided to flee to Russia. Aslanova told the paper that Quintana had given her permission to take Alexander, a claim he denies.

Aslanova did not respond to an email request from The Times.

Gómez worries whenever she hears about Ukraine or Russia in the news. But all she can do now is forgive her daughter-in-law for taking Alexander.

“I want to stay in a state of love, hopeful that he’ll be here,” Gómez said.

Quintana said the international custody dispute has been made even more difficult by the war. Ukraine recognizes the international treaty known as the Hague Convention on the Civil Aspects of International Child Abduction, which establishes procedures to return a child to the state of their habitual residence.

But the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in the Netherlands announced last month that it could no longer guarantee Ukrainian obligations under the treaty because of the war.

Quintana had a better chance of getting Alexander out of Ukraine but now that he is in Russia it may be near impossible, said California attorney David Lederman, who handles Hague Convention child custody cases.

“In Russia, you’ve got a country that isn’t a treaty member,” Lederman said. “You roll the dice. I don’t know Russian laws, but you’d be looking at the domestic Russian law as to whether or not there should be a return” of the child.

It does not matter if Quintana has a court order from a California judge; such orders do not have any jurisdiction in foreign countries, Lederman said.

Gómez worries about her son attempting to go to Russia to try to regain custody of Alexander. He showed her the video of the Russian soldier holding his passport.

“Sometimes, when something like that happens, you already have negative thoughts, and I was thinking, ‘Thank God that he’s here,’” she said of her son. “Imagine if he would have been in Ukraine [during the invasion]. Thank God he was here in California.”

But Quintana refuses to give up hope and continues to look for ways to bring his son back to the U.S.

“This is all I think about doing,” he said. “All I think about is bringing my son home.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.