Is it fair to blame Gascón alone for L.A.’s violent crime surge? Here’s what the data show

Throughout his first year in office, Los Angeles County Dist. Atty. George Gascón’s critics have drawn a straight line from the progressive prosecutor’s policies to dramatic increases in homicides and shootings.

Proponents of the effort to recall Gascón have accused him of creating a “pro-criminal paradise” and causing a crime spike through policies aimed at reducing mass incarceration, including his refusal to try juveniles as adults, prosecute certain misdemeanors or file most sentencing enhancements.

But an analysis of the L.A. County district attorney’s office filing rates, homicide solve rates and crime statistics paints a far more complicated picture of the surge in violence than the one some of Gascón’s enemies have sketched.

Although recall proponents claim there are no consequences for criminals in L.A. County, records show that during Gascón’s first year in office, prosecutors filed felonies at a near identical rate to what they did during Dist. Atty. Jackie Lacey’s two terms as the county’s top prosecutor. When it came to less serious misdemeanor cases, Gascón did file far fewer charges than Lacey, records show.

Prosecutors brought charges in 53.8% of all serious or violent felonies — including murders, sexual assaults and shootings — referred by police in 2021, and 58.2% of all felonies, according to data The Times obtained through a public records request. Under Lacey, prosecutors filed charges in 54.4% of serious or violent felonies and 57.6% of felonies overall from 2012 to 2020, records show.

While prosecutors’ felony filing rates have not changed since Gascón took office, law enforcement’s success in capturing dangerous criminals has. The Los Angeles Police Department solved 77% of all homicides in 2019, but that figure fell to 66% last year. In sheriff’s department territory, that clearance rate fell from 71% in 2019 to approximately 40% last year, according to data provided by the agency.

D.A. Gascón’s critics mount another recall campaign while he defends first year of reforms.

Homicides, aggravated assaults and car thefts are also climbing in jurisdictions that are home to more traditional prosecutors, including Sacramento and San Diego, leading some criminologists to suggest those who blame Gascón for Los Angeles’ recent bloodshed are overreaching.

“We are seeing very similar trends elsewhere. ... It’s not unique to Los Angeles,” said Magnus Lofstrom, director of criminal justice at the Public Policy Institute of California, which often publishes studies on crime trends. “It’s not unique to the period in which Gascón was in office as the L.A. County district attorney.”

Gascón’s policies appear to have had a much more direct impact on misdemeanors, records show. He has largely barred prosecutors from filing charges he says are linked to addiction or homelessness — including disturbing the peace, simple drug possession, loitering and public intoxication.

Prosecutors filed charges in just 43% of misdemeanor cases presented by police last year. In contrast, the office prosecuted 86% of all misdemeanors brought to its attention while Lacey was district attorney. Recently, some cities in L.A. County have become so frustrated with Gascón’s refusal to file charges in low-level cases that they are seeking to reclaim jurisdiction from his office.

More than 42,000 misdemeanor cases were rejected countywide in 2021. Roughly 12,000 of those were presented by the L.A. County sheriff’s department, and Sheriff Alex Villanueva says the lack of low-level prosecutions is emboldening thieves.

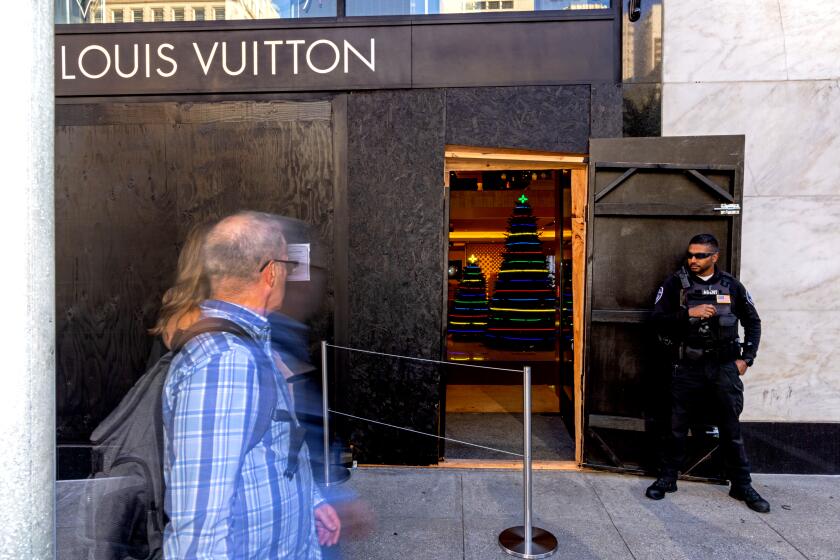

In a recent interview, Villanueva said policies like those of Gascón and San Francisco Dist. Atty. Chesa Boudin have created a revolving door where people arrested for petty theft or shoplifting are free to strike again and again without consequence.

“He’s giving people license to steal, knowing there’s no recourse. ... He’s just taking a license to not prosecute any petty theft that involves shoplifting,” Villanueva said. “That has been horrendous for the retail industry. Actually, one of the biggest damages they have to their profit margin is theft.”

A 2021 Times investigation, however, raised serious questions about the extent of financial pain retailers were feeling from such crimes. Burglaries fell by 24% in areas patrolled by the sheriff’s department from 2019 to 2021, while larceny dropped by 7% in that time frame, records show.

Industry groups and politicians are sounding alarms over the thefts. But in some cases, the statistics they cite are inflated or flat-out wrong.

But Villanueva argued that his own department’s data can’t even capture the problem.

“It’s to the point now that we can’t even rely on normal statistics because people have just given up on reporting because there’s no consequence,” he said.

Gascón has faced near relentless criticism since taking office. Law enforcement leaders have said his initial blanket bans on trying juveniles as adults or seeking life sentences against those accused of heinous crimes have robbed victims of their right to individual justice and helped drive a spike in violent crime. The policies have led to outrage over extreme cases that ended with defendants receiving short sentences for gruesome crimes, which led Gascón in February to relent on some of his all-or-nothing policies.

Two of the five leading candidates in the L.A. mayor’s race have endorsed the recall, and all have levied some form of criticism about his policies in recent months. On Thursday, recall organizers said they had amassed 200,000 of the nearly 567,000 signatures they need to force a recall election.

Gascón says he is “terrified” by the homicide spike in the region. In 2021, 397 people were killed in the city of Los Angeles, the most homicides since 2007, marking a 53% increase from 2019. The number of people shot in the city also leapt by 54% in that two-year span, records show.

Murders surged by an even higher rate in areas patrolled by the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department, jumping 77% from 2019 to 2021.

Nearly 400 people have been killed in L.A. in 2021, marking a 50% increase since 2019 and the loss of 15 years of progress driving down such violence.

But Gascón insists that those who try to make a broader link between his policies and violent crime are being disingenuous.

“If the currency of safety was harsh penalties and lots of prosecutions, then there are counties and parts of the country where that continues to be the case, yet their violent crime has gone up,” he said. “The problem is those that are my detractors are not blaming those prosecutors for their increases in crime, but they are blaming me.”

John Pfaff, a law professor at Fordham University, says it is the fear of getting caught, not the fear of a lengthy sentence, that deters violent criminals. He said the significant drop in how frequently LAPD and the sheriff’s department are solving murders is likely more of a factor in the crime spike than anything Gascón has done.

LAPD Chief Michel Moore has declined to discuss Gascón in public settings, saying he does not want to get involved in the political fray around the district attorney. He declined an interview request for this story through a spokesman, who did not respond to questions about the LAPD’s plummeting solve rate.

While Villanueva has been one of the leading voices attributing the increase in violence to Gascón, he backpedaled in a recent interview after being confronted with his own department’s low solve rate, saying the spike in killings cannot be blamed on any one agency or factor.

“There’s not one thing you can pin, because the decision to kill somebody, heat of the moment or cold calculated business decision, psychopath, you know whatever the case, there’s a lot of drivers there,” he said. “There’s not one variable, so it’s a complex formula. He’s just contributing one part of that complex formula.”

Villanueva went on to blame “the defund movement” for the decrease in solved homicides in his jurisdiction and said he has lost 25% of his detectives in the past year.

While violent crime has increased in jurisdictions of more traditional prosecutors in California in recent years, the uptick generally has not been as sharp as it was in Los Angeles.

In San Diego, where Dist. Atty. Summer Stephan has clashed with Gascón over his policies, homicides jumped 34% countywide from 2018 to 2020, state records show. In neighboring Orange County, home to conservative Dist. Atty. Todd Spitzer, homicides rose from 73 to 107 from 2019 to 2021 — a 32% rise — while aggravated assaults increased by 18%, according to sheriff’s department records.

The San Diego district attorney’s office is reclaiming its right to prosecute a number of cases linked to a violent 2019 crime spree that left two men dead.

But in Sacramento, where Dist. Atty. Anne Marie Schubert has repeatedly attacked Gascón over crime rates during her campaign for attorney general, violence actually surged more between 2019 and 2021 than it did in L.A. Homicides went up 67%, according to city records, while aggravated assaults jumped 43% in that time frame.

Asked about The Times analysis, recall proponents held fast to the idea that Gascón is responsible for the increase in violence. Tim Lineberger, a spokesman for the recall effort, said criminals are more likely to use firearms or engage in violence now, because of the reduced penalties they will face under Gascón.

“It would require a complete suspension of reality to suggest George Gascón has not played a major role in the rapid deterioration of quality of life and public safety in Los Angeles. When you don’t hold criminals accountable, all hell breaks loose, and that is exactly what you are seeing play out today,” he said in a written statement.

“Gascón’s entire agenda is geared towards letting violent criminals and repeat offenders off early, easy, or with no consequence at all,” Lineberger continued. “The results are predictable and the direct connection is inherently obvious.”

Lofstrom, of the Public Policy Institute, said that while it’s natural for the public to look at a violent crime surge and search for someone to blame, trying to make a one-for-one connection between a district attorney’s policies and crime rates is a fool’s errand.

“There are so many factors that affect crime rates under normal circumstances, it is going to be very difficult to point to a particular D.A.’s impact on crime rates convincingly and credibly,” he said.

Some data, or the lack thereof, also raise questions about Gascón’s misdemeanor policies.

While he campaigned on the idea of offering low-level offenders diversion instead of detention, Gascón admitted during a recent interview that he has no idea how many of the 42,000 defendants he’s declined to prosecute either received drug treatment or were entered into any kind of formal diversion program.

More than 25,000 of those defendants were arrested for public intoxication or simple drug possession, records show.

That lack of treatment has spurred concern from smaller police agencies. Sgt. Christian Hauptmann, a Glendale police spokesman, said while he doesn’t believe people struggling with addiction need to be jailed, they can’t simply be turned back out on the street either.

Under Lacey, defendants accused of addiction-related crimes could be diverted into treatment programs to avoid jail time after being charged, though some expressed concern that the initiative helped only a fraction of the defendants it could have aided.

Los Angeles County Dist. Atty. Jackie Lacey has been a major player in advocating for mentally ill defendants. But some critics say her programs are not expansive enough

Hauptmann said he was worried that the lack of enforcement had led to more drug use in Glendale, where the number of fatal overdoses doubled in 2021. The district attorney’s office rejected 61% of all misdemeanors presented by Glendale police last year, according to data provided by Hauptmann, who said city officials were considering asking their city attorney to start prosecuting misdemeanors to remove their cases from Gascón’s purview.

“If you get arrested for being in possession of an illegal substance … it should go through the court system, and you should be offered help. They’re not even offering to help these people,” he said.

Glendale is not alone in seeking to reclaim jurisdiction over misdemeanors from Gascón. In recent months, city councils in Manhattan Beach and Whittier also approved resolutions to explore prosecuting misdemeanors through their city attorney’s offices due to frustrations with Gascón’s policies. West Covina and Beverly Hills have also made similar requests, according to Alex Bastian, a special advisor to Gascón.

But under California law, district attorneys have the final say over who has jurisdiction to prosecute misdemeanors, and they would have to grant those cities permission to take over cases. Gascón already denied Manhattan Beach’s request.

“Manhattan Beach does not have the infrastructure nor the resources to adequately and efficiently handle criminal cases,” Bastian said. “Having our office handle these cases would result in better outcomes that advance public safety.”

Surges in certain property crimes also have dogged Gascón. Grand theft auto shot up by 24% in areas patrolled by the L.A. County sheriff’s department last year, records show, mirroring a troubling trend from Gascón’s time in San Francisco. Car break-ins exploded during his eight years in office there — the city reported more than 31,000 auto burglaries in 2017, the worst year in recorded history — which critics were quick to blame on Gascón’s refusal to prosecute low-level offenders.

But Gascón said he does not believe his misdemeanor policies have had an impact on crime in either county. Many of the largest population centers in L.A. County, including Los Angeles and Long Beach, for example, prosecute their own misdemeanors, he said.

“If those policies were the cause of more public disorder on the low-level part of the equation, then the city of L.A. would be doing incredibly well, but they’re not,” he said.

The only thing the two sides seem to agree on is that a proper evaluation of Gascón’s impact on crime will take time.

To Villanueva, that means the district attorney’s reluctance to seek the harshest possible sentences or try juveniles as adults will eventually lead to irredeemable violent offenders returning to victimize L.A. County again and again.

To Gascón, that means asking for patience and asking the public to break from the idea that the traditional approach to public safety was perfect, even as violence rises.

“It requires that all of us take a deep breath. ... The policies that I’m implementing, I believe that they will work because they’ve worked in other places, but that will take some time,” Gascón said. “The assumption is we are somehow coming from a good place to a bad place.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.