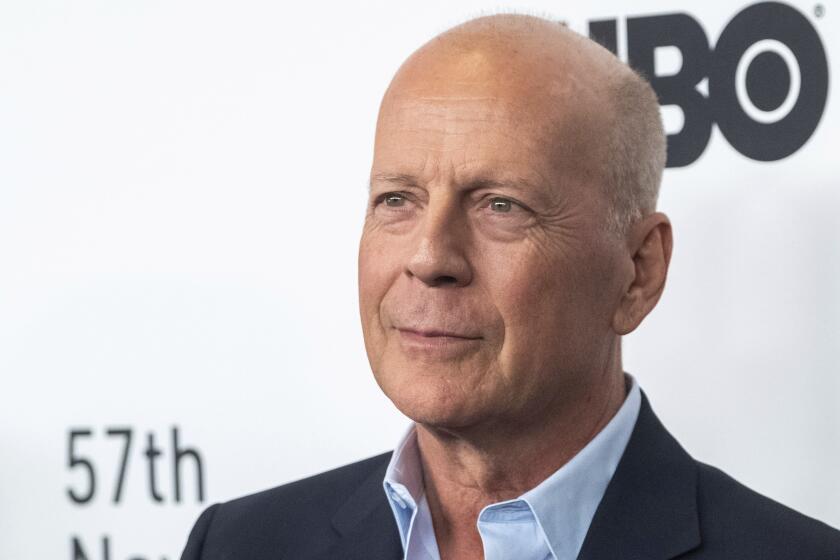

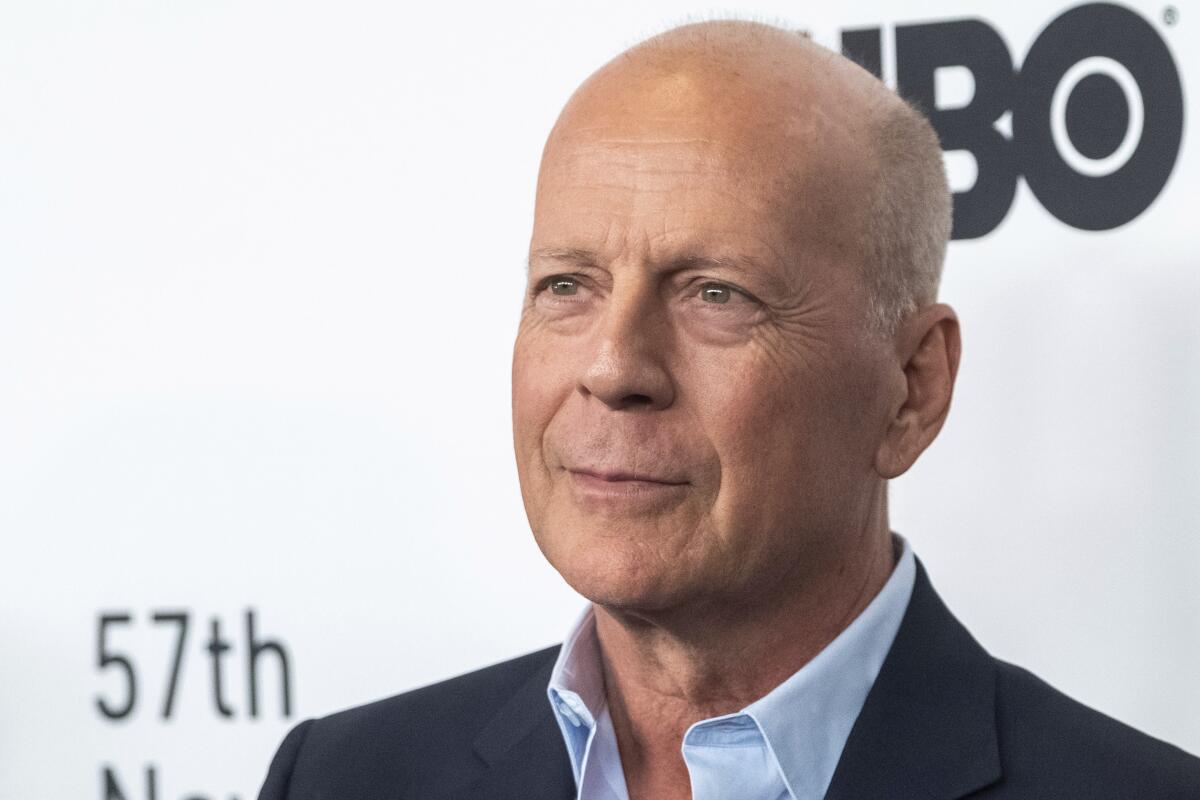

Bruce Willis’ aphasia battle: Living in a country where you don’t speak the language

Living with aphasia has been compared to living in a country where you don’t speak the language.

Gestures, sign language or other forms of communication may not be much help. And the people who want to help you struggle to understand.

“You know what things are. You are the person you were — but others don’t know that,” said Lyn Turkstra, a professor of speech-language pathology and neuroscience at McMaster University in Canada. “All of a sudden, you can’t express thoughts and feelings as you once could, and if it is progressive, you’re feeling it slip away gradually.”

Bruce Willis’ retirement from a four-decade acting career after an aphasia diagnosis has put the little-known disorder in the spotlight. People living with aphasia, as well as their caregivers and advocates for treatment of the disorder, say they hope his diagnosis will help reduce the stigma of invisible illnesses and lead to better understanding of a frustrating, isolating condition that affects about 2 million Americans.

Willis’ diagnosis has already sparked a surge of interest in the condition, said Darlene Williamson, the volunteer president of the National Aphasia Assn., a nonprofit organization that helps patients and their caregivers. The Willis family’s news echoes other celebrity health decisions, including Betty Ford’s 1974 battle with breast cancer, Michael J. Fox’s disclosure in 1998 that he had Parkinson’s disease, and Angelina Jolie’s preventive double mastectomy in 2013.

“How many people have ever heard of aphasia? Pitifully few,” Williamson said. “If you tell someone, ‘I have aphasia,’ they have no idea what it is. Just for the word itself to be meaningful is a huge desire for our community.”

In interviews with The Times this month, nearly two dozen people who were on set with the actor expressed concern about Willis’ well-being.

Aphasia is not a cognitive disorder and does not affect intelligence. Most frequently triggered by strokes or other brain trauma, the condition makes it difficult to speak, to find the proper words and to understand what is said or written. In less frequent cases, aphasia can be brought on by neurodegenerative diseases that cause cognitive issues.

For both types of aphasia, the resulting communication difficulties can lead to shame, embarrassment and frustration.

“The general public assumes that if someone doesn’t respond, they are intellectually challenged,” said Roberta DePompei, a retired professor of speech-language pathology at the University of Akron. “They are treated like a child, when inside, they are still the same person. It becomes humiliating to be treated that way.”

The condition is more common than Parkinson’s disease or multiple sclerosis but far less known. Two years ago, 86.2% of Americans had not heard of aphasia, while about 7% knew that it was a communication disorder, according to a survey by the National Aphasia Assn.

Language is “one of the things that make humans really human,” said Dr. Mario F. Mendez, a behavioral neurologist at UCLA. Because aphasia affects a person’s ability to use symbols — whether words, sign language, musical notations, even Morse code — the condition can be difficult to work around.

How aphasia affects someone and how it can be treated vary widely. Mendez said he recently saw three distinct aphasia patients in one day: the first struggled to remember certain words; a second distorted the pronunciation; and a third simply couldn’t understand what the doctor was saying.

The patient who couldn’t recall terms was able to express himself by explaining around them and is a good candidate for speech therapy. Meanwhile, the visit with the patient who struggled to understand language led to “a very difficult conversation with his wife.”

For patients whose aphasia is brought on by “insidious, slowly progressive” degeneration, rather than a stroke, an early warning sign is often trouble finding a word, Mendez said. Sometimes called the “tip-of-the-tongue phenomenon,” people are forced to stop midsentence and search for what should come next.

Bruce Willis is the latest entertainment luminary to go public with an aphasia diagnosis. Others include Emilia Clarke and Sharon Stone.

That type of aphasia, called primary progressive, is understudied and underdiagnosed, in part because people are afraid to go to the doctor when they start experiencing warning signs, Williamson said.

Early diagnosis and intervention are key so patients can start language therapy and develop a system of communication for when speech eventually fails, she said. Talking to a doctor, a speech therapist and a support group will give families more time to sort out finances and decision-making duties, and to set expectations for how life can take shape.

With good medical care and speech therapy, most patients whose aphasia is related to a stroke or another brain injury should see some improvement, Williamson said. People whose aphasia is brought on by cognitive decline should not expect the same outcome, she said, and should instead focus on “maintaining for as long as possible.”

Whether people living with aphasia can participate fully in society, including working, depends on the severity of their case and whether they are facing other health issues stemming from the same incident that caused the aphasia, such as mobility problems caused by a stroke.

People who worked with the 67-year-old Willis on recent films raised concerns that he did not seem to be fully aware of his surroundings and struggled to remember his lines, The Times has reported. Productions reworked their schedules and scripts to compress his dialogue and the amount of time he spent shooting.

An actor who traveled with the star fed his dialogue through an earpiece, known in the industry as an “earwig,” according to several sources. Most action scenes, particularly those that involved choreographed gunfire, were filmed using a body double.

“No matter what the cause of aphasia, there’s no cure,” Williamson said. “Almost no one who’s diagnosed with aphasia is ever 100% who they were before. We never talk in terms of a cure. We talk in terms of living successfully and returning to participation in life.”

Some people with aphasia may be able to return to work with reasonable accommodation. For example, if their disorder makes it harder for them to type, they could dictate rather than write, Williamson said. Others may choose to find another line of work that isn’t as taxing, or turn to volunteering rather than working full time.

People living with aphasia that is coupled with cognitive decline, she said, “do continue to work for a period of time until it just doesn’t make sense anymore.”

There have been advancements in how the condition is treated.

When DePompei, the retired speech-language pathologist, began helping patients with aphasia more than 40 years ago, the manuals at the time recommended practicing with words in categorical lists, and there were picture cards. One typical session might focus on the kitchen: “Stove.” “Refrigerator.” “Eggs.”

Today, she said, understanding of the condition is more nuanced and practical, addressing not just the mechanics of speech but the social and psychological dimensions related to its loss.

“Each of us has something we want to communicate,” she said. “Finding out how to keep an individual with aphasia supported in the community in which they have always lived is essential.”

Often this means working with cellphones or tablets and breaking through the social isolation that being speechless entails. Sometimes, she said, it is more important to say, “I love you,” or “Turn on the TV,” or “I’m hungry.”

Williamson said people living with aphasia have been helped enormously by smartphones, which allow them to order meals, find taxis and make doctor’s appointments without speaking.

The news of Willis’ diagnosis has sparked hope that, with increased awareness, more money could be raised to find a cure or better treatments for aphasia. Two years after Fox announced his Parkinson’s diagnosis, he created a research foundation that has raised more than $1 billion to find a cure.

Aphasia brought on by a stroke or another brain injury is not always a one-way street toward deeper isolation. The brain’s elasticity sometimes allows for new connections to be made across broken circuits, especially in the case of injuries or strokes.

Sara Culver was 42 when she suffered a high blood pressure stroke that led to her aphasia. Almost 20 years later, she has recovered, and together with her husband, Tim, volunteers with the Aphasia Recovery Connection sharing her story with others.

“The stroke completely destroyed her speech center and affected her right side,” said Tim Culver. She spent three months in the hospital and three more at the Centre for Neuro Skills in Irving, Texas, near where they live. She had her own apartment and, with the help of a caregiver, began finding the words that she had lost.

Culver estimates it took his wife about 10 years to get back to where she was, and today she is working again, tutoring students at the local college in mathematics and algebra.

“They told me she would plateau at six months,” Culver said. “But she continually improves in her ability to speak. It takes time, but people can regain their ability to communicate.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.