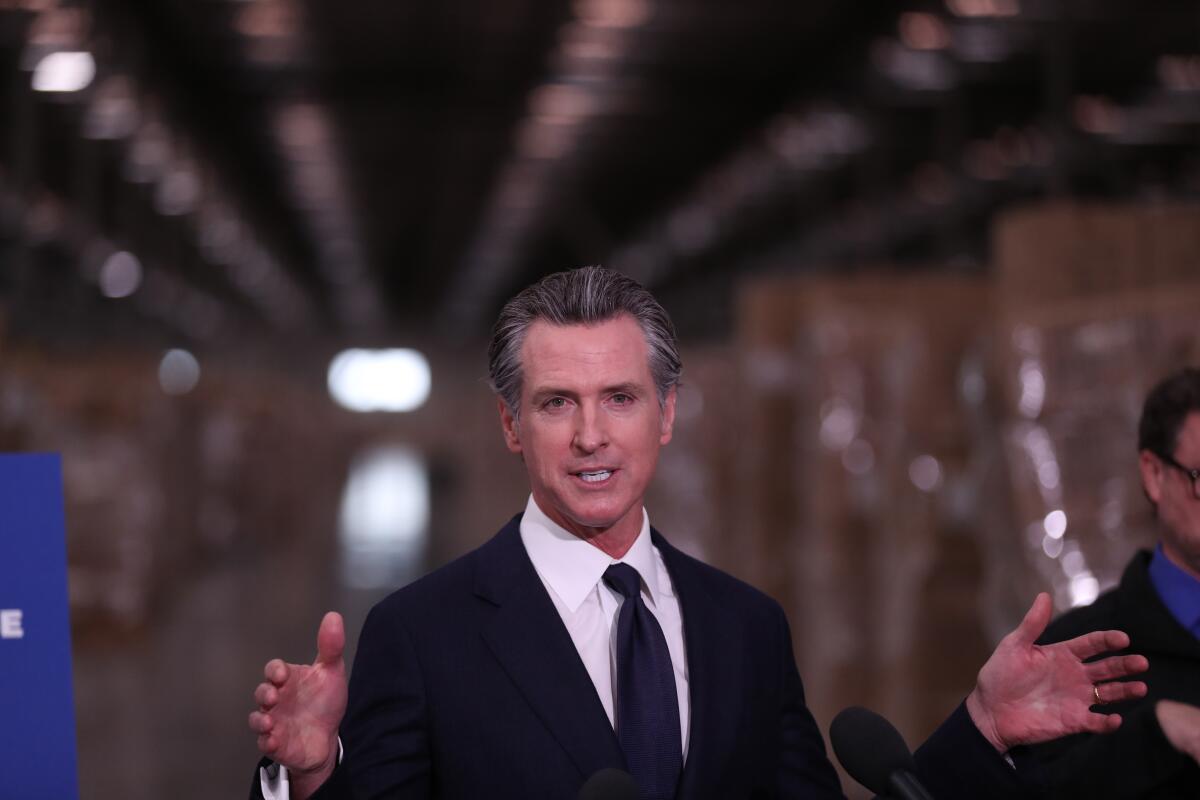

Newsom scales back some special pandemic rules, but not California’s state of emergency

SACRAMENTO — Gov. Gavin Newsom on Friday rescinded a slate of COVID-19-related executive orders in response to signs of a subsiding pandemic, but did not end California’s nearly two-year-long state of emergency despite criticism from Republican lawmakers that he no longer needs its immense executive powers.

The governor’s office summarized 19 provisions in executive orders that will be immediately terminated, which included requirements that all state-owned properties be made available for emergency use and state agencies to identify facilities for housing and medical treatment.

Another 18 provisions will expire at the end of March, including those that protect COVID-19 relief funds from garnishment and allow for virtual corporate and public meetings, according to Newsom’s office. Additional executive orders that limit liability for data breaches on telemedicine platforms and allow video assessments for those with COVID-19 symptoms who receive in-home supportive care would be rescinded on June 30.

Newsom administration officials said California’s COVID-19 state of emergency needs to stay in place, however, because it is necessary to continue the state’s COVID response. Using that broad authority, the Democratic governor waived statutes and laws to allow testing and vaccination programs and to ensure that California had enough capacity in hospitals to handle another surge in cases.

“Many of us know families, communities, individuals who benefited, maybe had their life saved, because these provisions have been in place up until this point,” said Mark Ghaly, secretary of the California Health and Human Services Agency. “It isn’t by accident or mistake that California has one of the lowest death rates of a large state.”

Since he declared a state of emergency on March 4, 2020, Newsom has issued 70 executive orders involving the COVID-19 pandemic that addressed a range of issues, including price gouging, halting evictions and postponing the deadline for filing tax returns in 2020. The vast majority of those have either been rescinded or have expired.

Under the 1970 California Emergency Services Act, the governor has broad authority to respond during a state of emergency such as a pandemic. The governor can “make, amend, and rescind” state regulations and suspend state statutes and has the power to redirect state funds to help in an emergency — even funds appropriated by the California Legislature for an entirely different purpose. The governor also has the authority to commandeer private property, including hospitals, medical labs, hotels and motels.

The California Supreme Court in 2021 upheld an appeals court ruling that affirmed Newsom’s emergency powers. Two state Republican lawmakers had challenged Newsom’s power, arguing he had no right to issue an executive order requiring ballots to be mailed to the state’s 22 million registered voters before the Nov. 3, 2020, election.

The high court ruled the law was constitutional because it required the governor to terminate a declared state of emergency as soon as possible and also allows the Legislature to end it by passing a joint resolution.

For more than a year, GOP lawmakers have been pushing for the Democratic-controlled Legislature to take action. However, it wasn’t until last week that Senate President Pro Tem Toni Atkins (D-San Diego) agreed to hold a hearing on the proposal, now scheduled for March 15.

“I think it’s outrageous that he would recognize that these executive orders can expire but that his claimed prerogative to rule the state by decree will remain in effect. The Emergency Services Act is very clear that the governor must terminate the emergency at the earliest possible date that conditions warrant,” said Assemblyman Kevin Kiley (R-Rocklin), who sponsored a bill in his chamber to end the emergency.

Ann Patterson, the governor’s legal affairs secretary, said rescinding the state of emergency would “cripple” California’s response to the pandemic.

Patterson also said that all state mask and vaccine mandates, including those for schoolchildren and healthcare workers, were enacted under the state health and safety code. Even if the state of emergency ends, those mandates would remain in place until rescinded by the state’s top public health officer.

Under Newsom’s executive powers that will remain in place, the state will continue to largely waive licensing requirements for healthcare facilities, workers and testing labs — actions designed to boost the state’s vaccination and testing capacity and expand the scope of practice for pharmacists, technicians and EMS workers. Pharmacies are allowed to provide testing and vaccinations and mobile vaccination clinics are permitted.

Patterson noted that declared states of emergency remain in effect for disasters that struck years ago, including the deadly Camp fire in 2018 that decimated the Northern California town of Paradise. A 2015 emergency declared by then-Gov. Jerry Brown over tree morbidity in California’s forests also remains in effect, she said. Those emergencies give the administration more flexibility to repair damage, reduce threats and allow communities to rebuild, she said.

“The emergency isn’t over when the ground stops shaking. It’s not over when the fire is put out. It’s not even over when we’ve provided immediate medical attention or secure damaged bridges after an earthquake,” Patterson said. “The effects of a disaster can continue for years.”

Patterson said Newsom has proven to be very judicious when exercising his emergency powers during the pandemic. With the actions announced Friday, the governor’s office said only 30 of 561 executive order provisions related to the pandemic will remain in place by this summer.

However, until the state of emergency ends, Newsom will retain his expanded emergency powers — including the authority to change laws, reappropriate funds without legislative approval and enter into no-bid contracts.

In the first months of the pandemic, Newsom came under fire for a secretive $1-billion mask deal his administration signed in 2020 with BYD, a Chinese electric car manufacturer that had been ramping up its political presence in California in recent years. The contract was kept under seal for weeks, prompting bipartisan concerns from lawmakers.

Last year, Newsom brought in Blue Shield of California to oversee the state’s distribution of COVID-19 vaccines, prompting objections from county officials and questions about preferential treatment of a longtime donor to the governor.

Critics have argued that many of the no-bid contracts awarded under Newsom’s emergency powers have gone to companies that have donated millions to the governor or on his behalf through behested payments, which they say creates the appearance of a pay-to-play system.

Senate Republican leader Scott Wilk (R-Santa Clarita) introduced a bill this week that would prohibit a state agency from awarding no-bid contracts to companies that have made a charitable donation on behalf of the governor in the year leading up to the gift.

“I am deeply concerned about the increasing use of massive no-bid contracts,” Wilk said in a statement.

Times staff writer Melody Gutierrez contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.