California approaches pandemic record for all hospitalizations

In a stunning sign of the heavy burden facing California’s healthcare system, the total number of people hospitalized statewide is approaching the peak of last winter’s COVID-19 surge, even as there are indications that the rise in coronavirus-positive patients may be starting to ebb.

Late last week, California averaged 52,000 people daily in its hospitals for all reasons — more than was seen during any seven-day period during the summer Delta surge. California’s pandemic record of 55,000 people hospitalized daily was set last winter, according to state Department of Public Health data reviewed by The Times.

Coronavirus-positive patients continue to account for a wide margin of the overall census. As of Tuesday, 15,179 such patients were hospitalized statewide, the highest since Jan. 29, 2021, state data show.

The number of coronavirus-positive patients in California’s intensive care units has also surpassed the summer peak.

On Tuesday, California recorded 2,404 coronavirus-positive ICU patients; the summer peak was 2,128. Still, the latest figure is a fraction of the pandemic high of 4,868 coronavirus-positive patients in the ICU, recorded on Jan. 10, 2021.

However, there are some signs hospitalization increases are growing less steep. From Dec. 28 to Jan. 4, the overall number of hospitalized coronavirus-positive patients swelled 69%. The next week, it rose 53%.

The growth from Jan. 11 to Tuesday was far more modest: about 23%.

But even with the apparent slowdown, some areas — including Sacramento and San Francisco counties — are at all-time highs for coronavirus-related hospitalizations.

In recent weeks, California’s emergency rooms have experienced strain even worse than during last winter’s deadly surge.

Earlier this month, California was averaging 47,000 daily emergency room visits for all reasons over a weekly period. By contrast, visits during the summer Delta surge peaked at 42,000.

The recent peak in overall emergency room visits has been worsened by those seeking coronavirus-related treatment in ERs, where there have been nearly 12,000 recent daily visits for this type of treatment across California. That’s worse than the previous record of nearly 11,000 visits a day, recorded last winter.

California’s state epidemiologist, Dr. Erica Pan, said last week that “we are seeing near-crisis levels” of emergency room overcrowding in some areas.

With fewer hospital workers, it’s harder to admit patients from the ER, which then keeps ambulances waiting for long periods to drop off patients, resulting in a worsening of 911 response times to new callers, Pan said.

Many hospital emergency rooms have been so crowded, and staffing so scarce because of employee infections, that a number of scheduled surgeries and procedures have been postponed. Those delays can affect the health of people needing treatment for cancer or other important medical issues, in which prompt care can make a difference.

“It’s just harder to try to be in so many places with all of our patients,” said Sandra Beltran, a registered nurse in the emergency room at Olive View-UCLA Medical Center in Sylmar. “It’s tiring. You’re literally, for 12 hours, going from room to room.”

Because the hospital is short on staff, patients being treated in the emergency room have waited 20 or 30 hours for a bed elsewhere in the hospital, Beltran said. That has a domino effect on the ER, where waits grow longer and staff have had to find new ways to assess patients.

“People are being seen in the hallway,” the nurse said. “We’ve come to that.”

Officials have also urged residents to avoid coming to the emergency room for non-emergency reasons — such as getting coronavirus testing.

“Do not show up to the emergency room and ask to be tested because what you do is you bombard the emergency room,” said Dr. Clayton Chau, Orange County’s health officer.

The N95 masks will be available at pharmacies and community centers across the United States.

In Arcadia, Methodist Hospital of Southern California is licensed for more than 300 beds but was able to staff fewer than 200 on Wednesday, limiting how many patients could be admitted, according to Senior Vice President Cliff Daniels.

“We continue to scramble every day to find nurses so we can staff more beds” because so many healthcare workers are either infected or caring for family, he said.

So far, the hospital has not sought to immediately bring back asymptomatic healthcare workers who have tested positive for the coronavirus — a step that California authorized to ease staff shortages at hospitals. It is, instead, relying on travel and registry nurses when it can hire them.

The staffing strain at the Arcadia hospital has collided with its growing number of COVID-19 patients, which surged from zero to 60 in the past month and a half, Daniels said.

The result is a logjam for patients being treated in the emergency room but who are ill or injured enough to need to be admitted. Daniels said the wait for a bed to open has exceeded 50 hours.

The rise in reported cases is the fastest accumulation of infections in the history of the pandemic.

At Providence Holy Cross Medical Center in Mission Hills, there were only eight patients hospitalized with COVID a little over a month ago. That number now exceeds 100, “a phenomenal increase in a very short period of time,” chief executive Dr. Bernard Klein said.

Some people dismiss the threat of Omicron, but “tell that to the 11 patients in my ICU who are fighting to survive,” Klein said, urging people to get vaccinated against the virus and follow up with booster shots. “It still is a very dangerous infection.”

This time around, “what has made this surge so unique and challenging is that the Omicron variant is so infectious that it’s hitting our employees and their families,” the hospital executive added. As of Wednesday morning, Klein said roughly 8% of the hospital’s workforce was out and it was operating at more than 90% of its capacity.

The hospital has again set up a tent to sort patients outside, reopened designated units to care solely for COVID patients and is holding off on inpatient elective surgeries that are not “emergent or urgent” — the result of shortages in both staff and blood, Klein said.

“Our ER, and pretty much every ER that I know of, is holding patients that are admitted because we don’t have a bed in the main hospital,” the hospital executive said. That “has potentially huge ramifications,” including longer waits for new patients trying to get into the emergency room and delays in unloading ambulances and sending them back out, he said.

The hospital COVID census in San Bernardino County has nearly tripled from 398 before Christmas to 1,107 as of Jan. 13.

The one-two punch of patient demand and staffing shortages is also straining intensive care units. Statewide, the proportion of staffed adult ICU beds that are available has fallen from 22% at the start of the month to just above 16% as of Tuesday, state data show.

In the San Joaquin Valley, the share is even lower: 10.3%. That state-defined region covers Calaveras, Fresno, Kern, Kings, Madera, Mariposa, Merced, San Benito, San Joaquin, Stanislaus, Tulare and Tuolumne counties.

Should the region’s hospitals report having less than 10% of their ICU beds available for three straight days, state health officials will implement surge protocols.

Across Southern California — which the state defines as Imperial, Inyo, Los Angeles, Mono, Orange, Riverside, San Bernardino, San Diego, San Luis Obispo, Santa Barbara and Ventura counties — 15.4% of cumulative staffed adult ICU beds were available as of Tuesday.

“Staffed” is the key there. As Chau noted Tuesday, “If you have an ICU bed, you have a ventilator, but you do not have staff to work it, it is a non-usable ICU bed.”

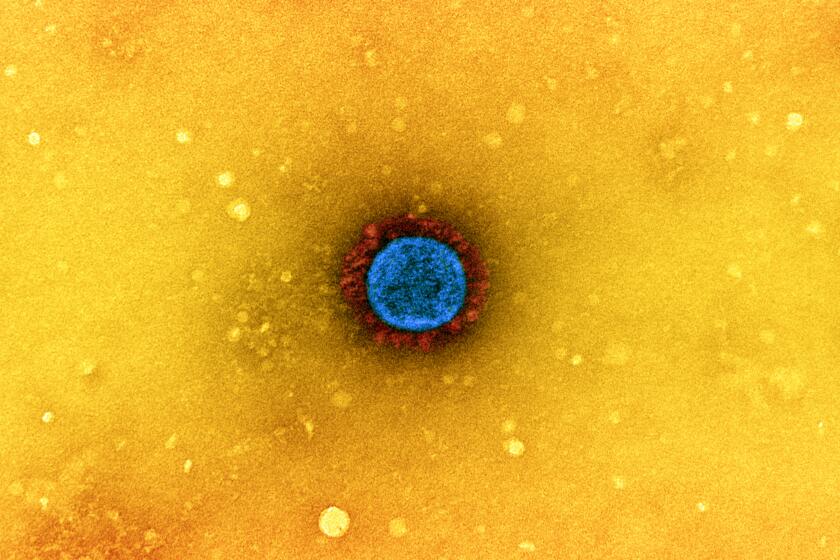

When the coronavirus attacks the body, the immune system steps up, trying to respond quickly and powerfully enough to stop the virus from running wild.

Although some health officials have said the recent COVID-19 deaths are probably the result of the Delta variant, the L.A. County Department of Public Health in recent days has noted that many fatalities have occurred among people who were infected when Omicron was clearly the dominant variant.

Officials are now warning of a significant death rate this winter, potentially worse than during the summer Delta wave. Already, Los Angeles County’s death rate in recent days has exceeded that of the summer surge.

As of Tuesday, L.A. County was averaging 45 COVID-19 deaths a day over the last week, a rate that has doubled in a week. Over the summer, L.A. County tallied a peak death rate of 37 deaths a day.

“Tragically, we are prepared for an even higher number of deaths in the coming week,” L.A. County Public Health Director Barbara Ferrer said. “With unvaccinated individuals 22 times more likely to die from COVID-19 compared to those fully vaccinated, residents should not delay getting vaccinated and boosted, as these measures are saving lives.”

A leading World Health Organization official says the worst of the COVID-19 pandemic — including deaths, hospitalizations and lockdowns — could be over this year if huge inequities in vaccinations and medicines are addressed quickly.

California has averaged about 106 COVID-19 deaths a day over the last week, a rate that has doubled since the end of December. During the state’s summer surge, California peaked at 135 deaths a day.

Nationwide, the United States has been averaging between 1,700 and 1,900 COVID-19 deaths a day, around the same as summertime. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention predicts that death rates will be stable or worsen in the coming weeks, with 1,500 to 5,000 deaths a day in the week leading up to Valentine’s Day.

The CDC has warned that its models have been less reliable recently, with actual deaths greater than what had been forecast.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.