‘Wait for a good time : - ) Don’t fight!’ A guide to help teens persuade parents to let them get vaccinated

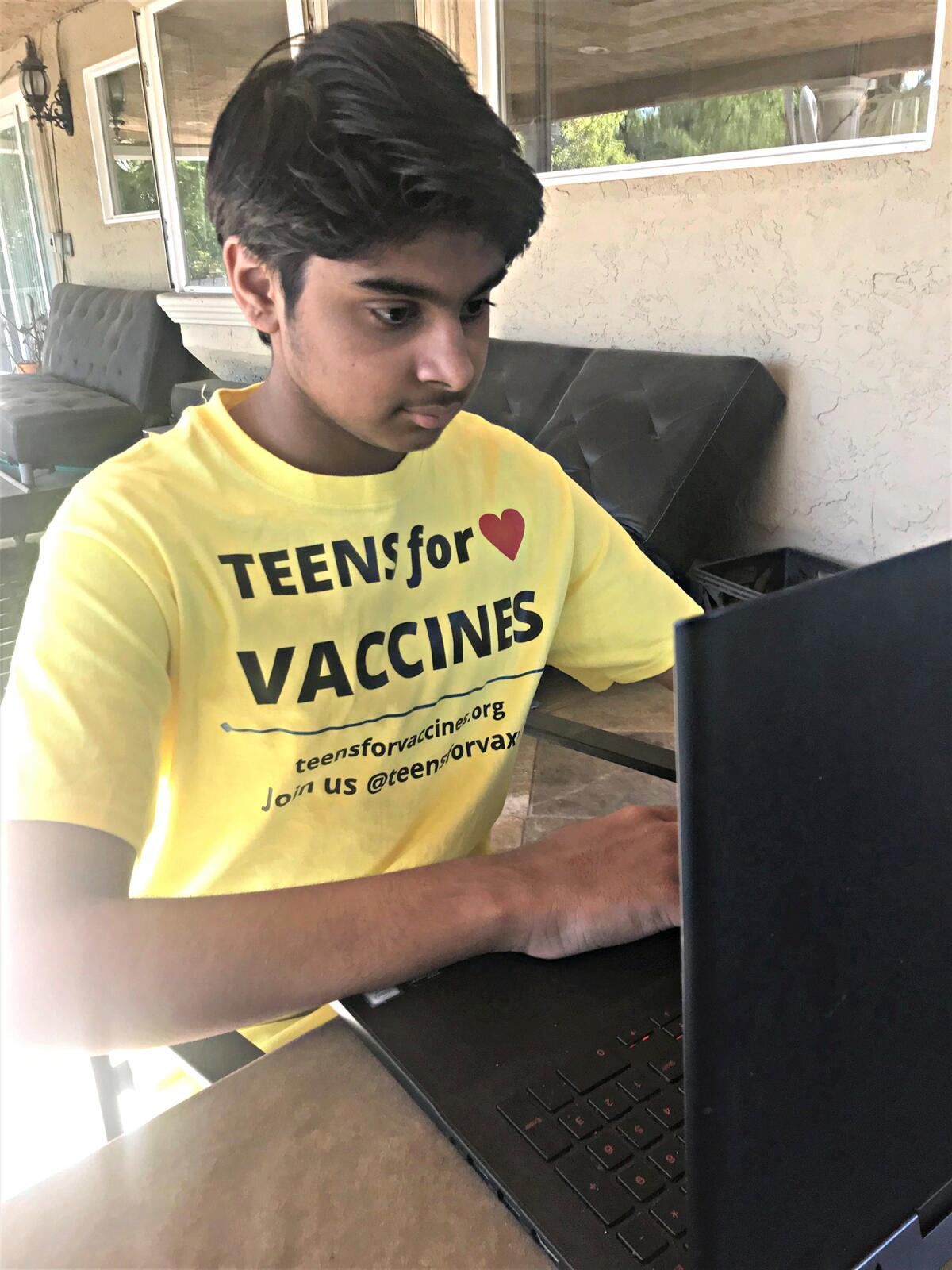

When he has small slices of free time, wedged in between schoolwork and studying for academic quiz competitions, Arin Parsa scrolls through Reddit.

The 14-year-old from San Jose searches for posts about vaccines, and comments whenever he thinks he can be helpful, sometimes sharing a public health department’s hotline or congratulating a poster on overcoming a fear of needles. Last fall, Arin, who founded an organization called Teens for Vaccines, spotted a post from a 16-year-old in Ohio who said his parents were opposed to the COVID-19 shot.

“Can i get vaccinated without my parents’ consent?” the boy wrote.

No, not in Ohio, Arin responded, before adding a note of encouragement — “You aren’t alone” — and sharing a link to a guide he helped create for teens hoping to persuade their parents to let them get vaccinated. A couple of tips from the guide include talking to your parents when they seem relaxed, and emailing them information so they can look over it when they’re less busy.

“Wait for a good time : - ). Don’t fight!” it reads.

As the Omicron variant continues its infectious sprint across the nation, again forcing school closures, pushing hospital staff to their limits and obliterating any well-earned if naïve hope that this thing was nearly behind us, this latest wave has reminded us how little we can control.

And for teenagers, the defining decision of this pandemic — whether to get vaccinated — is often not legally theirs to make. Parental consent laws for vaccinations vary by state and region. A few places, including Philadelphia, already allow some teens and preteens to self-consent to get the COVID-19 vaccine.

And though some advocates, including Arin and Kelly Danielpour, another young Californian, who founded VaxTeen, argue that it’s a right that every teen across the nation should have, there are also some legislative efforts moving in the opposite direction.

In recent months, lawmakers in some states, including South Carolina and Ohio, have crafted bills to prevent public schools from requiring COVID-19 vaccinations, and in November, Alabama’s governor signed into law a bill requiring parental consent for vaccinations, carving out an exception to a preexisting state law allowing minors 14 and older to consent to medical treatment.

“At the very least, all high schoolers should be able to self-consent for vaccines,” Arin said. “I think teens are responsible enough to make that decision.”

A sixth-grader at the time, Arin started Teens for Vaccines in 2019, during the height of the nation’s worst measles outbreak in years. Inspired by a fellow teenager’s congressional testimony about his mother’s anti-vaccination views, which the teen said had been shaped by online misinformation, Arin began researching the history of the anti-vaccination movement.

Using Reddit, he shared trusted vaccine sources with teens and parents, including many people who had questions about the HPV shots. He often responded with links to information and personal tidbits, remarking that he’d noticed a needle’s sensation for a second or two while getting the HPV shot but hadn’t had any reactions.

The pandemic years, he said, have felt like a blur, punctuated by fielding media requests and virtual events, such as a vaccination kickoff event last summer with Dr. Anthony Fauci, the White House’s top medical advisor.

The process has been tiring at times, but Arin has found it fulfilling to connect with teenagers across the country who have signed on as Teens for Vaccines ambassadors, among them a Louisiana senior who once considered COVID a joke but then became sick, and a Texas sophomore whose parents, QAnon supporters, have refused to let her get the shot.

Another ambassador, Ani Chaglasian, a junior from Glendale, reached out to Teens for Vaccines last fall after her parents, who were then wary of the shots, told her they didn’t want her to get inoculated.

Her family is Armenian, Ani said, and in her community, especially among immigrants from the former Soviet Union, it’s not uncommon for people to have a deep distrust of the government. She did her best to focus on logical, scientific points when discussing the topic, but her mother wouldn’t budge, which terrified Ani, who worried about contracting the virus and passing it along to her grandmother, who has lung cancer.

In her role as president of her school’s Medical Club, she learned of several other students facing a similar predicament and she began creating a slideshow that her peers could use to help talk to their parents. It’s critical not to approach these conversations with any aggression, Ani said, noting that she’d found that a line that often works for smaller things — like getting your parents to let you go to the movies — sometimes worked in this situation too.

“Saying, ‘My friend, who you know really well and who is really smart, did it,’” said Ani, who estimated that she and other student volunteers had helped play a role in persuading around 1,000 people, both students and parents, to get vaccinated.

Among them was her own mother, who eventually relented after watching how many opportunities Ani had lost out on because she wasn’t vaccinated, including losing her job as a scribe at a local hospital. Ultimately both of her parents got the shots as well, Ani said, noting that she’d had a breakthrough with her father during a conversation about how she couldn’t live with herself if she passed the virus on to him and he died.

She’s still dedicated to the work, she said, and wants other parents to know that teenagers who want the shots aren’t making some contrarian push for independence.

“They’re not trying to rebel and they’re not brainwashed,” she said. “They want you to let them get vaccinated.”

More than anything, teens want this pandemic to be over, said Ani, who has volunteered at a peer-to-peer suicide line.

She often thinks back on conversations with teenagers who told her they were sitting in their bedrooms, feeling desperately alone. School had been their escape, they told her, and now they felt trapped. Others said they felt helpless, knowing they were burning years they could never get back — a point that resonated with Ani.

“I was a freshman when the pandemic started and I’m graduating next year,” she said, sighing.

She thinks back on the days of virtual learning and worries about holes in her knowledge and that of her classmates. Many days after a teacher ended a class, several blank screens would stay up — a sign, she came to learn, that her classmates had fallen asleep.

Although she was initially relieved to return to in-person classes and to see plans for prom and other events start to take shape, Omicron has, again, brought uncertainty. Last week, on her first day back after the holidays, half of her classmates were out and many classes were being taught by substitutes. She felt terrified to pull her mask down even momentarily to eat.

“I’ve never seen this many kids absent from school,” she said. “It’s really scary.”

For Arin, Omicron ushered in a feeling of deep fatigue.

“We’re tired of this pandemic, we’re tired of the infighting,” he said. “Can we set it aside and just fight COVID? It’s overdue that we get our lives back.”

Some of his favorite memories from before the pandemic are of traveling to Illinois for a national quiz competition, catching up with old friends and savoring each bite of deep-dish pizza. When this is all behind us, Arin says, one of the things he’s most looking forward to is traveling to India to visit his grandparents. And the fastest way to get there, he knows, is higher vaccination rates.

Not long ago, Arin commented on a post from a young person who said they were unvaccinated. He asked the poster to consider how it would feel to spread the virus to an immunocompromised person.

“Ah, yes,” the commenter wrote back, “ignore everything i said and go for the ‘unvaccinated people are killing everyone’ line.”

“Hey there, didn’t ignore what you wrote. Thanks for sharing.”

“Sorry i was just used to people hating people who are unvaccinated.”

“It’s okay. I totally understand. Thanks for writing back. These are unfortunate hard times for everyone.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.