How Joan Didion’s Sacramento childhood shaped her life, and her take on California

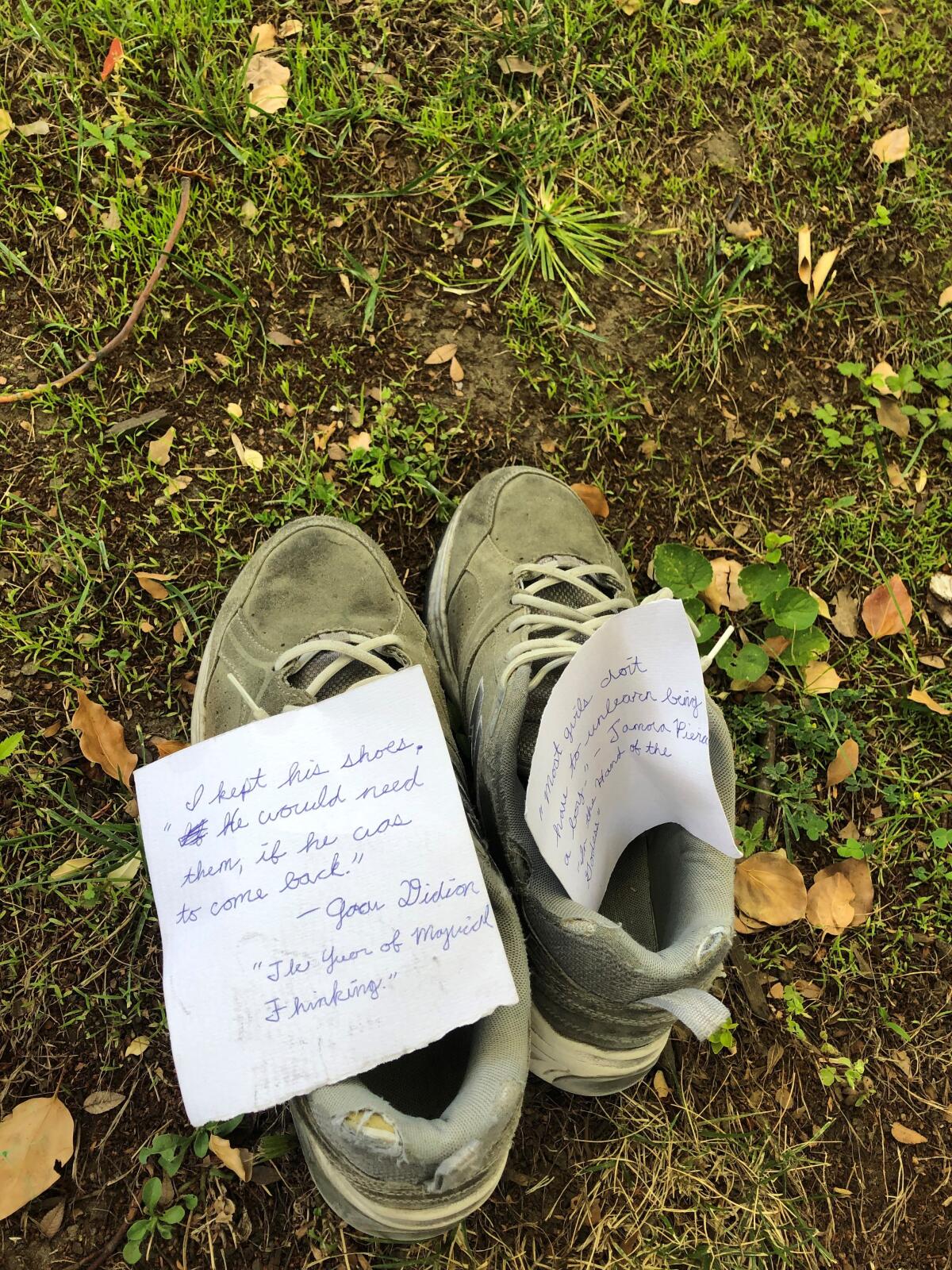

SACRAMENTO — The tennis shoes, dirty and worn to their foam core around the ankles, appeared on the front lawn of Joan Didion’s childhood home a few months ago — a talisman of grief to an author who knew it intimately.

On top was a note quoting “The Year of Magical Thinking,” in cursive script written by a hand that seemed shaky.

“I kept his shoes. He would need them, if he was to come back,” it read.

Danielle Anderson, who moved into Didion’s elegant mansion in Sacramento earlier this year, took it as “an indicator to us that this house is something special to Sacramento.”

Thursday, as a cold rain gave way to glowering gray skies, more offerings appeared on Anderson’s steps: a white poinsettia in a red pot, three bouquets of the supermarket variety, and later, a vase of yellow roses.

All were left to honor the acclaimed writer who passed away, a daughter of the Capitol City whose relationship with it was knotty. She was at times nostalgic of Sacramento, and at times homesick for a tight-knit community. But her dreams didn’t fit on her wraparound porch, or even in the fields and ranches that defined this agricultural valley in her youth, or under the dome of the state building a few blocks away.

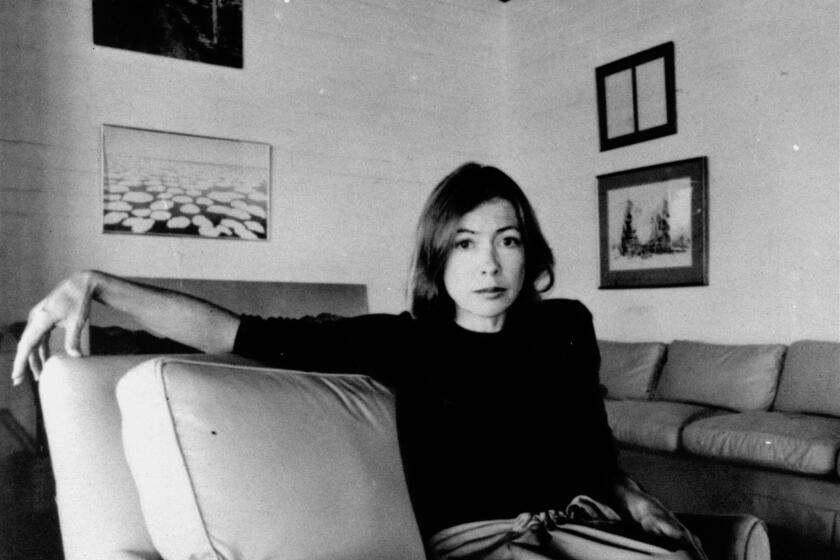

Didion bridged the world of Hollywood, journalism and literature in a career that arced most brilliantly in the realms of social criticism and memoir.

“She had a complicated relationship with Sacramento. She also had a real love for it,” said Rob Turner, co-editor of Sactown Magazine, who interviewed Didion in 2011. “It perhaps was constraining while she was here, she had her eyes set on bigger things.”

It is a place Didion outgrew, but that never outgrew her. At least once a week, said Anderson, someone knocks on the front door or stops her husband’s yardwork to ask if this was Didion’s old house.

For many, Didion herself was evidence there is more to this always-trying town than meets the eye.

“For the longest time, I was one of those kids that always wanted to leave Sacramento,” said Harrison Daly, 23, standing at the cash register of the Avid Reader, a local bookshop where Didion‘s books were doing brisk business Thursday. Daly began changing his mind about the city after he found a copy of “Democracy,” Didion’s fourth novel, at a library book sale.

Her ability to capture grief touched him and gave him a sense of pride that Sacramento turned out such talent, an indicator of an underground “cultural boom even though it appears to be quiet,” he said.

Didion was born in Sacramento on Dec. 5, 1934, and if she had grown up in San Francisco or Los Angeles, she would have formed a much different take on California than she did in the Central Valley. Her ancestors had arrived in Sacramento in the mid-1800s. Stories of the pioneer experience shaped her childhood and were a focus of “Run River,” her first novel. She later lamented that book as contributing to the California myth, but it provided a glimpse of how Sacramento was transforming from a farm hub and sleepy state capital into the sprawling region of 2.3 million people it is now.

Didion spent the last two years of high school in a wealthy corner known as Poverty Ridge, so named because of the city’s early history of devastating floods. Before big levees were built along the American River and muddy Sacramento River, the two waterways would overtop their banks, forcing poverty-stricken Sacramentans to escape inundation by converging on one of the town’s few hills.

Joan Didion continues to resonate in California, even with a generation nothing like her.

Wealthy families such as the McClatchys — owners of the Sacramento Bee — would soon learn that Poverty Ridge was a safe spot to build their mansions. Didion’s father, Frank Didion, purchased one of these houses in the 1940s — a nearly 5,000-square-foot blend of Colonial Revival and Prairie School styles — at the corner of 22nd and T Streets, moving the family from a smaller home a few blocks away.

For Didion, the city’s rivers were her constant companion, an escape rather than a fear. She’d raft them and swim in them and later dissect hydrologic reports to better understand how humans had replumbed them. These studies shaped her later writings — such as the 2003 book “Where I Was From” — that debunked myths about Californians being self-reliant. As she noted, California was dependent on the federal government for flood control, irrigation and so many other services.

She lived in the grand “Didion House” for just two years, before she graduated from C. K. McClatchy High School in 1952 and departed for UC Berkeley. While at McClatchy, she wrote for the Bee’s rival, the Sacramento Union, filling a role typically relegated to women during that era. It gave her more of a window into the region’s upper crust, which she portrayed in “Run River.”

“I was working at the society desk. I did weddings. I didn’t cover weddings, I just wrote about them,” she told Turner in his Sactown Magazine interview. “I wouldn’t call that reporting.... They would send you accounts of what the bridesmaids were going to wear and stuff like that, and you would write it up.”

For many current McClatchy students, Didion is a footnote among other illustrious graduates, including retired Supreme Court Justice Anthony M. Kennedy and California Supreme Chief Justice Tani Cantil-Sakauye.

But for former student Annabelle Long, who like Didion left Sacramento for UC Berkeley and aspires to be a writer, there is pride and kinship in sharing a hometown, and leaving it. She didn’t read Didion until she took a course on the 1970s in college, where “The White Album” was required reading. It began her a “crash course” on other Didion works and an understanding of a Sacramento that sometimes can’t shake the chip on its shoulder, compared with several of California’s other major cities.

The celebrated prose stylist, novelist and screenwriter who chronicled American culture and consciousness died Dec. 23 at 87.

“I’ve been spending a lot of time thinking about her Sacramento versus my Sacramento,” said Long, who just finished an essay about her own youth in the same neighborhoods Didion frequented. “I don’t think Sacramento is all that successful in being the cultural place it tries to be. Sacramento tries very hard and I think that’s the same Sacramento that she wrote about as well.”

After departing for UC Berkeley, Didion occasionally returned to Sacramento — to see her parents or take her late daughter Quintana to see rivers and levees and other quirks of her old stomping grounds. She was distantly involved in some local real estate dealings. But in her 2011 interview, she said she hadn’t been back to Sacramento since the 1990s, and there is no record of her embracing local attempts to honor her literary career and celebrity, including being inducted into the California Hall of Fame in 2014.

It is not entirely clear why, past her teens, Didion so detached herself from Sacramento unlike, say, Greta Gerwig, who produced a love letter to her hometown in the 2017 film “Lady Bird.” But the city was a key character in several of her books.

In “Slouching Towards Bethlehem,” she wrote of its significance not just to her but to California.

“That is what I want to tell you about: what it is like to come from a place like Sacramento,” she wrote. “If I could make you understand that, I could make you understand California and perhaps something else besides, for Sacramento is California.”

As darkness fell on the flowers, Anderson, who lives where Didion once dreamed, contemplated what she would do with the living tributes. She wanted to leave them out where others could see them, share in their meaning and grief. But it was too sad to think of them dying there in the cold. She decided she would bring them in on Christmas, arrange them in a vase, and give them a place of honor.

And, she says, she will then do a toast — to Didion, her life, and the beauty of strong women.

Chabria reported from Sacramento, Leavenworth from Berkeley.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.