L.A. mayor joins Native Americans in solstice celebration and prayer for COVID dead

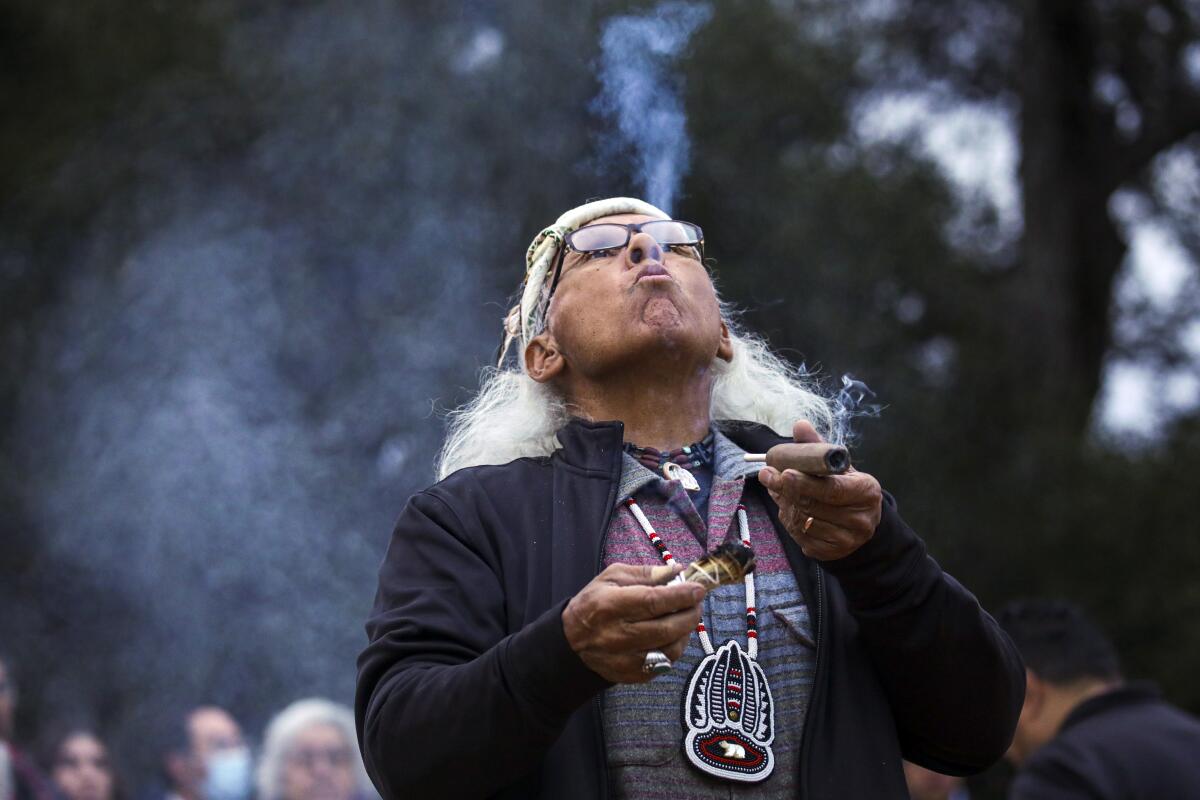

The earthy smell of burning sage filled the air Tuesday morning as dozens of Native Americans and city officials led by Mayor Eric Garcetti gathered at a west San Fernando Valley nature preserve to honor the winter solstice and pray for those who perished in the COVID-19 pandemic.

During a blessing ceremony held in a glade of century-old oaks at the Chatsworth Nature Preserve, Garcetti stood with hands clasped and eyes closed at the edge of a prayer circle as Alan Salazar, an elder in the Fernandeño Tataviam tribe, wafted sage smoke over him with a fan of eagle feathers.

“This is a day to give thanks to Mother Earth,” Salazar said, “and a day to pay off debts and make amends to people you’re angry with.”

Later, Garcetti shared a prayer of his own with those in attendance. “We’ve lost 27,000 souls — more than that now,” he said, referring to the number of people who have died in Los Angeles County due to the ongoing pandemic. “So, my prayer is for this city to be safe. I don’t want to bury one more Angeleno.”

The unusual, hastily organized event was billed as a “community wellness gathering” co-hosted by the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power, which owns the 1,325-acre property, and the Fernandeño Tataviam Band of Mission Indians and Santa Ynez Band of Chumash Indians.

Beth Pratt, who wears a mountain lion tattoo on her left arm, helped to raise $87 million for a cougar crossing over the 101 Freeway.

The winter solstice, the shortest day of the year, is when the Northern Hemisphere of the Earth is tilted as far away from the sun as possible during the year. In Los Angeles, it was at 7:59 a.m. Tuesday.

The event was not just about sacred celestial phenomena, however. It came at a time when Los Angeles is formally developing strategies to increase diversity and compensation equity at all levels of the city workforce, and correct harms that its educational systems have perpetrated against minority students including Native Americans.

In October, Garcetti announced the beginning of a process to rename downtown’s La Plaza Park, which has been informally known as Father Serra Park. In collaboration with Councilmember Mitch O’Farrell, an Indigenous cultural easement will also be created to give local tribal communities priority access to the park for the practice of traditional ceremonies.

The Los Angeles Unified School District Board of Education earlier this year unanimously voted to dedicate $10 million to support tribal organizations. The money is intended to help address critical student service needs related to academic achievement in the district’s coronavirus recovery effort and to ensure that schools are places that affirm their unique linguistic, cultural, and historical backgrounds.

Against a backdrop of rocky hills and twisted oaks, political leaders including state Sen. Henry Stern, chairman of the Natural Resources and Water Committee; O’Farrell; Los Angeles City Councilmember John Lee; and DWP Board President Cynthia McClain-Hill each suggested, in turns at a podium, that the time had come to return at least some of the land and water taken from Native Americans whose ancestors occupied Los Angeles County since time immemorial.

Despite a California law intended to end over-pumping of aquifers, a frenzy of agricultural well drilling continues in the San Joaquin Valley.

For Rudy Ortega Jr., president of the Fernandeño Tataviam tribe, which has 860 members, that kind of talk was long overdue. His ancestors fought to retain their family lineages within geographic regions until the lands were overtaken by Anglo American expansion.

Now, the tribal members are facing the long and expensive process of gaining federal recognition of their Native American status — a step needed to establish a land base, a measure of sovereignty and to qualify for assistance with healthcare, education and protection of sacred sites.

With that goal in mind, the tribe has been actively identifying various parcels it might one day seek to call its own again. Among them is Chatsworth Reservoir.

“The notion of taking back land that was once ours is not new,” Ortega said, “but it is new to this administration, and its leadership seems open to it.”

Beyond that, he said, “My father, on behalf of the tribe, in 1970 asked for the Chatsworth preserve area.”

The tribe’s inquiries about gaining control of the preserve have stirred concern among some locals who fear the acquisition might be a back door to building a casino.

Ortega wouldn’t rule that out under certain conditions at some future date. “Whatever the tribal leaders decide to do to improve our economy is up to them.”

But Marty Adams, general manager and chief engineer at the DWP, said handing over control of the preserve is out of the question.

“There’s a general sense of interest on the part of the city in finding open spaces that we could return to the tribes,” he said. “Here at Chatsworth preserve, however, we’re not talking about transferring ownership.”

“The discussions have been more along the line of, perhaps, providing them with an easement,” he added, “designed to provide them with greater access, or setting aside space for a fire pit for traditional ceremonies.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.