California created the nation’s first state reparations task force. Now comes the hard part

SACRAMENTO — Cash, land transfers, down payments to purchase homes and an overdue apology.

Those are just some of more than a dozen potential remedies for those affected by slavery and its legacy of discrimination that Black community activists have implored California’s Reparations Task Force to consider at public meetings.

The variety of opinions underscores the nine-member panel’s monumental challenge: crafting a historic reparations proposal that earns the support of Black Californians, who have pushed for justice for generations, and a majority of California lawmakers, whose constituents might not fully understand the scope of the trauma and need for atonement.

“People have differences of opinion about the extent of harm that we’ve undergone, differences of opinion about the remedies that would in some way begin to remediate those harms and differences of opinion on who should be receiving any kind of reparations,” said Cheryl Grills, a professor of psychology at Loyola Marymount University whom Gov. Gavin Newsom appointed to the task force. “Now, undergirding all of that, is the reality that we also live in a society that has done a very poor job of informing the general public about what this country has done to Black people.”

Under state law, the task force is charged with investigating the history of injustice and brutality against Black people, “with a special consideration for African Americans who are descendants of persons enslaved in the United States.” The group must recommend ways to educate the public about its findings and propose a formal apology, potential compensation and other remedies.

In a year of national protests against racial injustice, state lawmakers approved Assembly Bill 3121 to force the state to begin to confront its racist history and systemic disparities that persist today.

California’s effort is the first of its kind in the nation, driven by the hope that the task force‘s work will inspire other states and the federal government to begin to repair the harms of centuries of slavery and the lingering effects.

State Sen. Steven Bradford (D-Gardena) said reparations were discussed this month at the 45th annual National Black Caucus of State Legislators conference in Atlanta, where he was honored for his legislative work that includes a state law authorizing the return of a property known as Bruce’s Beach to the descendants of a Black family that had been forced out.

Before Manhattan Beach shut it down, Bruce’s Beach was a famous Black-owned beach resort. Now, some want the city to atone for its actions.

Bradford said California’s reparations task force was also seen as a model, and lawmakers from other states asked him for advice.

But Bradford worries about the political difficulty of enacting sweeping reparations even in California, with a statehouse dominated by Democrats. Some of his colleagues may feel it’s “a bridge too far that they’re not willing to cross,” he said.

“I’m concerned because I’ve already heard from enough of my colleagues who kind of feel like ‘Hey, that’s not my fight, we shouldn’t be responsible for something that happened over 100 years ago,” Bradford said. “I’ve often said, if you can inherit generational wealth, you can inherit generational debt and the state of California as well as the United States owes a debt to African Americans who are descendants of slavery and helped build this country.”

Bradford and other members of the task force say community engagement throughout the process is critical to their mission to deliver a reparations proposal to the Legislature by July 1, 2023, that can become law.

Gov. Gavin Newsom authorizes returning the land known as Bruce’s Beach to the descendants of a Black couple that had been run out of Manhattan Beach.

Kamilah Moore, a 29-year-old reparatory justice scholar and Los Angeles-based attorney, was appointed to the task force by Assembly Speaker Anthony Rendon (D-Lakewood) and voted chair by her colleagues.

Moore said she’s accepted that the end result might not meet everyone’s expectations, but she intends to vet all options for reparations, including those that may seem hard to achieve.

“I’m planning to use this spot to be as radical as possible, at least to bring in the conversations around these issues,” Moore said. “We’re probably not going to recommend that the police get abolished in the state of California, but that doesn’t mean that I’m not going to try to invite an expert to come and provide testimony.”

Each task force meeting begins with public comment and Moore makes sure everyone who calls in gets a chance to speak. The task force is also working with UCLA’s Ralph J. Bunche Center for African American Studies on a community engagement plan.

“One way that we’re going to measure success is by virtue of buy-in from Black Californians and the Black community,” Moore said.

The plan includes listening sessions beginning in January to hear what people need and want, Moore said.

“I think that if we do a good job of listening across these different sessions that we plan to hold in the state that we will be able to discern some semblance of areas of convergence of thinking and build from that,” Grills said.

The listening sessions may sway the task force to come up with a plan that isn’t one-size-fits-all and instead includes a combination of reparations they gather from ideas in the community, Grills said.

“Hearing from the community is what’s most important,” said Lisa Holder, a civil rights trial attorney whom Newsom appointed to the task force. “Hearing about people’s lived experience, hearing about the trauma that people have experienced from racism, hearing about the wealth that real people have lost because of exclusionary policies and practices. Hearing from real Black people who are catching hell day to day is what is most important and that is one of the reasons why we are pushing for a community engagement process.”

Developing a plan to educate the public about the history of slavery and discrimination is also a key part of the assignment.

The state Legislature passed Assembly Bill 3121 to create the task force in the late summer of 2020, three months after video was released showing George Floyd dying under the knee of a Minneapolis police officer.

Holder said the imagery of Floyd’s killing forced those who had been in denial for decades to recognize racism in America. The challenge in California will be to go much further than recognition, she said.

“Repairing injustice requires people who have been systemically advantaged to not only recognize that advantage but to give up some of that advantage in order to repair the injustice and level the playing field,” she said.

“Now what’s very important is to start to have a truthful narrative around racism, and how it has been perpetuated for centuries and generations. When I say a truthful narrative, I want to juxtapose that to the dishonest narrative that has been the dominant narrative for 19th and 20th century that blamed African Americans for the disparate outcomes,” Holder said.

In public testimony before the panel, experts have explained that California has a long history of injustice to atone for, beginning as a “free state” with a disproportionate representation of white Southerners with pro-slavery views in public office who continued to tolerate slavery after it was banned in the state’s 1849 Constitution. Estimates suggest at least 500 enslaved people lived in California during the Gold Rush, said Stacey Smith, a professor of history at Oregon State University.

“It was one thing for the California Constitution to declare that slavery would not be tolerated,” Smith told the task force in September. “It was quite another thing to actually criminalize slavery, emancipate enslaved people, punish slaveholders, and give Black people protections for their freedoms.”

California’s Fugitive Slave Law of 1852 authorized slaveholders to use violent means to capture enslaved people who arrived in California before its statehood and escaped, or refused to return to slave states with their enslaver. The law made California an outlier among free states, many of which resisted capturing and returning enslaved people, Smith said.

“Much like the enslaved people in the U.S. South, those in California also faced brutal violence,” Smith said, providing examples of beatings at the hands of white people.

Around the same period, the California Legislature and state court barred Black people from providing court testimony against white people, excluded Black people from making homestead claims, denied state funding for Black children to attend public schools and refused to acknowledge petitions from Black activists seeking to change laws. An 1850 ban on interracial marriage in California between Black and white people lasted for nearly 100 years, Smith said.

Joseph Gibbons, an associate professor of sociology at San Diego State, testified this week about the consequences of New Deal-era government home financing programs that used the percentage of Black people in a neighborhood “as a direct criteria for investments,” known as redlining.

Gibbons shared an assessor’s evaluation of a Pasadena neighborhood in an official government document from 1939 that described the area as favorably located, but “detrimentally affected by 10 owner-occupant Negro families.”

“Although the Negroes are said to be of the better class, their presence has caused a wave of selling in the area and it seems inevitable that ownership and property values will drift to lower levels,” the assessor wrote.

“Until 1948, it was perfectly legal for house holders to band together and create these legally binding documents wherein they could not sell their homes to people of color,” Gibbons said. “It’s what we would know as ‘racial covenants.’”

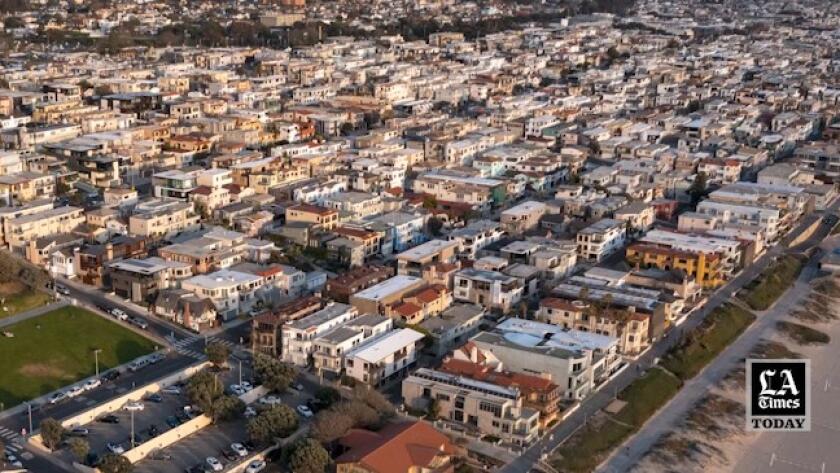

When those covenants expired or were finally made illegal, assessors devalued neighborhoods as Black people moved in. Redlining negatively affected the ability of Black residents to build wealth because they paid less favorable refinancing rates, Gibbons said. It also made neighborhoods more vulnerable to gentrification, which led to the displacement of Black residents and isolation for those who remained.

Bruce Appleyard, an associate professor of city regional planning at San Diego State, said in transportation, housing and land use, the public and private sectors created inequity through “a multidimensional and systematic array of discriminatory policies from the federal government on down.”

“This effectively created a unique form of American apartheid that must be corrected,” Appleyard told the task force this week.

Black residents have been barred from mortgage assistance and negatively harmed by highways that were constructed in their communities, tearing them apart and barricading the people who lived there from opportunities, Appleyard said. Urban renewal and eminent domain takings also led to the displacement of Black people, who were barred from buying houses in white affluent suburbs, he said.

“We do not fully evolve as empathetic beings as a community because of racism and injustice,” Holder said. “So this process of truth and reconciliation is important to everyone. White people, Latinos, Black people, Asian people — we are all experiencing trauma because of the levels of anti-Blackness in society. So we as a people need a healing and restorative process to become better human beings.”

Watch L.A. Times Today at 7 p.m. on Spectrum News 1 on Channel 1 or live stream on the Spectrum News App. Palos Verdes Peninsula and Orange County viewers can watch on Cox Systems on channel 99.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.