When Ernest Siva was a boy on the Morongo Reservation in Riverside County, he listened to the music and stories of his ancestors, who had lived in Southern California long before the land was called by that name.

He recalls running around a ceremonial fire on the reservation at age 5 as a weeklong ceremony honoring those who had died the previous year culminated with the burning of images in their likeness. Dollar bills and coins were thrown into the fire in tribute as tribal elders sang songs reserved for special occasions. Siva and his cousin chased after the singed money that fluttered out of the flames, largely ignoring the traditional lyrics in the background.

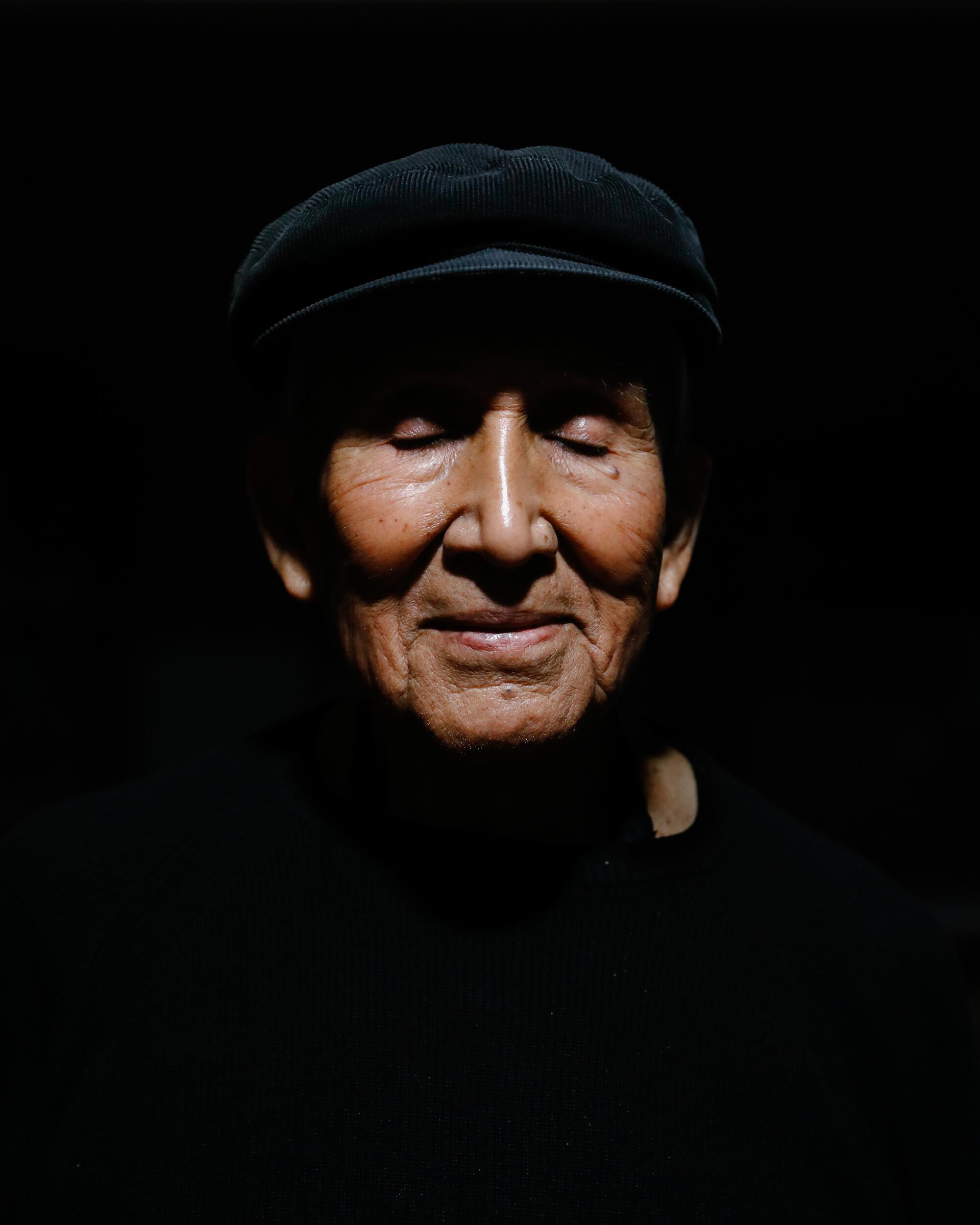

The specific words and rhythms are now distant memories for the 84-year-old Siva, a Cahuilla/Serrano Native American.

“My recollection is hearing those songs, but ... I didn’t learn any of those songs because they’re only sung for a specific occasion,” he said. “Once those ceremonies were over, and they stopped being held, we no longer had those songs.”

TOVAANGAR “The world.” From the top of Signal Hill, Los Angeles disappears in the haze.

The following year, the ceremony was hosted by another tribe, but over the years, the people who knew the Indigenous songs died without passing them on.

Siva is working to change that. For the last 25 years, the Banning resident has been a tribal historian with the Morongo Band of Mission Indians.

For thousands of years, the Serrano language was passed down through oral tradition. The word “Serrano” comes from the Spanish term for “highlander,” which is what the 18th century explorers called the Maara’yam people.

Stories were passed on for generations by elders, but Siva thinks by the 1950s, some of the oral history — as well as the Indigenous language, which has many dialects — had already begun to fade away.

Dorothy Ramon, Siva’s aunt, was the last “pure,” or fluent, speaker of the Serrano language.

In the 1920s, Ramon was forced to attend the Sherman Institute in Riverside, a boarding school meant to assimilate Native American children and strip them of their Indigenous traditions and languages. But Ramon and her siblings were encouraged by their grandfather Francisco Morongo to keep their language alive or risk losing their heritage.

The traditional Thanksgiving story got it wrong. How should you talk about the holiday with your kids?

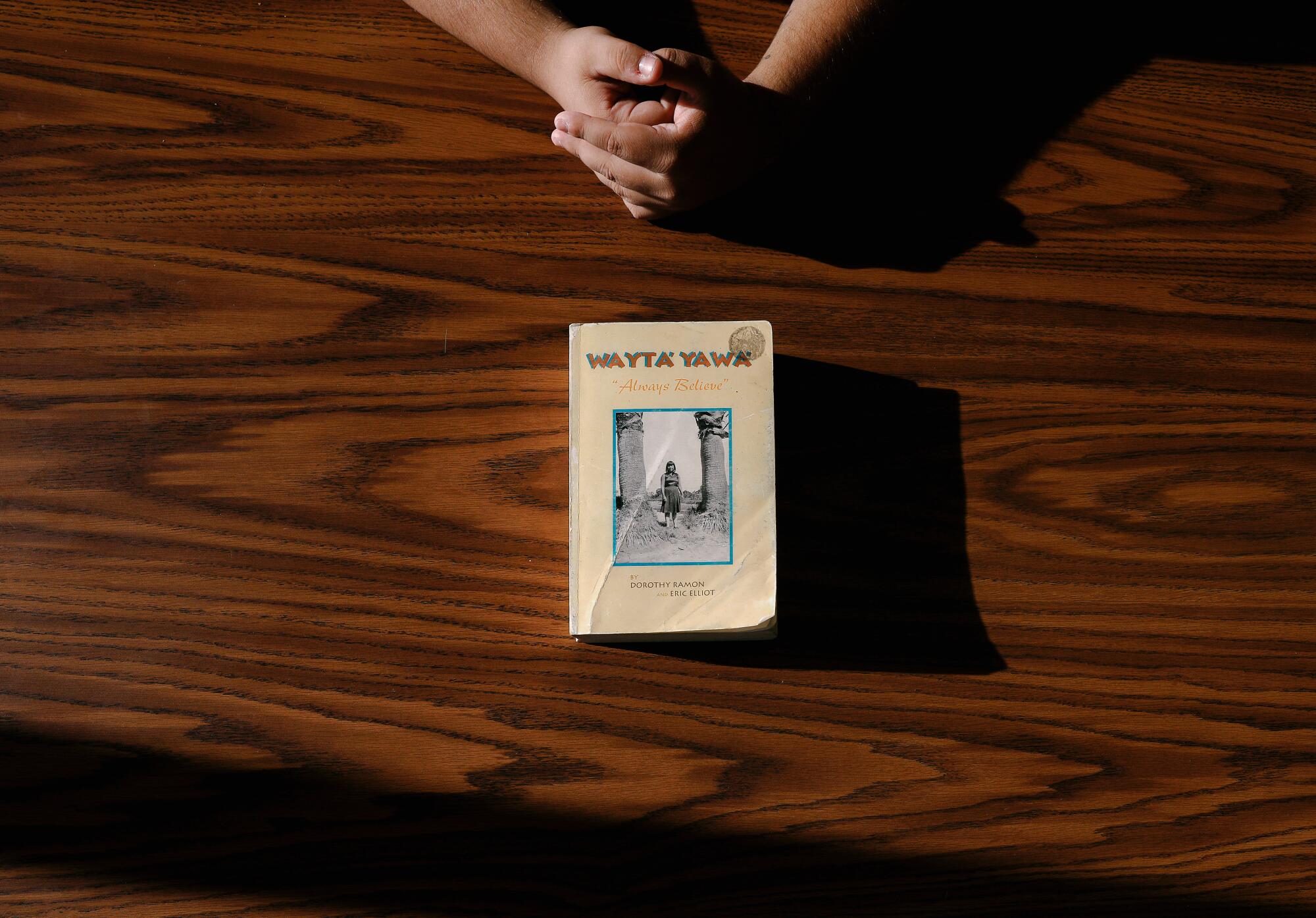

During the last 100 years, linguists have researched the Serrano spoken word. When Ramon was in her late 70s, she collaborated on a 12-year project with linguist Eric Elliott, a white man, who translated her stories into the 2000 book “Wayta’ Yawa’ (Always Believe).”

“It was a big surprise that she even worked with a linguist because she was on the shy side and kept to herself,” Siva said. “If it wasn’t for her, we wouldn’t have volumes of her stories.”

But when Ramon died at age 93 in 2002, the language all but died with her. Revitalization efforts over the last three decades, carried out by the Morongo and San Manuel Bands of Mission Indians, have worked to resurrect the language that was once spoken by people across the region.

Earlier this month, San Bernardino County formally recognized the language for the first time, even though Serrano people have been in the region since before the arrival of Spanish missionaries in the 1700s.

Siva’s work has had a large part in that. He devotes most of his time and energy to sharing the Serrano culture and language.

Siva contributes to Cal State San Bernardino’s language program through an arrangement between the San Manuel Band of Mission Indians and the university. A class on the Native American language was introduced over a decade ago, but today, it is offered as a full-credit course.

Carmen Jany, the coordinator of the California Indian Languages Programs at Cal State San Bernardino, said Siva’s instruction has been vital in keeping the Serrano language alive.

“I believe that his sincere desire to preserve and pass along the language and traditions of the local native cultures — evident in his generous gifts of time, talent and knowledge — is clearly a driving force behind these efforts,” Jany said in an email about Siva’s work.

After his aunt died, Siva and his wife, June, opened the Dorothy Ramon Learning Center in Banning, where they host Indigenous works of art, including theater, poetry and music. They also regularly give Serrano lessons.

One devoted student at the learning center is Mark Araujo-Levinson, a 25-year-old Latino who found the classes through a Google search.

The Riverside resident’s great-grandfather was Mixtec, a Mexican Indigenous group, and Araujo-Levinson’s fascination with languages began during childhood. But it wasn’t until after he had graduated high school and some friends told him about the Native American dialects in the region that he began to wonder why he hadn’t heard of them before. That curiosity set him on a journey to learn more about the Indigenous languages of California — and led him to Siva in 2017.

“At first, Mr. Siva was a little wary of the situation, just because I’m not from the reservation. But as our friendship grew, he became more encouraging,” Araujo-Levinson said. “These past years have truly been a blessing for me. It means a lot to me that he taught me the language, and how he holds me in such good regard.”

Araujo-Levinson, a mathematics student at Cal State San Bernardino who views grammatical rules like equations or theorems, shares his love of languages — including the Serrano dialects — on his YouTube channel and even earned a job with the Morongo Cultural Heritage Department as a language preservation specialist.

Siva relishes having such a natural — if unconventional — student.

“He surprises everyone with his ability to pick up and to understand and all that’s required to write,” Siva said. “Not many people can do that.”

About two years ago, Araujo-Levinson translated a tale told in 1918 by Yuhaaviatam leader Santos Manuel to anthropologist J.P. Harrington. The story, titled “What Owl Said” and initially written in English and Spanish, was translated into Serrano with Siva’s help.

It begins:

Kwenevu’ kesha’ ’aweerngiva.’ (There was a bad storm.) Hakupvu’ weerngtu.’ (It was raining a lot.)

The story describes the darkened skies and four boys playing in the rain. Then an owl visits an old man who was sleeping. The owl tells him to sing and play his rattle in the morning. The story ends with the old man’s music chasing away the rain.

Puuyu’ taaqtam hihiim taamiti.’ Puuyu’ peehun ’a’ayec ‘amay’ nyihay kwana.’ (All the people saw the sun. They were all happy.) Kwenemu ’api’a’ puuyu’ taaqtam poi’cu’ chaatu.’ (After that, all the people began to sing.)

’Ama’ ’ayee.’ (That’s all.)

The end of such storytelling — in the native Serrano language — is what Siva fears. He never set out to become Morongo’s tribal historian. As a teenager, he wanted to play the saxophone but after decades as a teacher, from elementary schools to universities, he understood the responsibility to preserve his language.

He said his family used to struggle for the right word in Serrano and came up short.

“They would say, ‘Oh well, so long, language,’ ” he said.

“That was the ending of our ways, you know,” Siva said of the long-ago celebrations on the reservation.” Without having those things ... without having the ceremonies, they were gone,” he said of the Indigenous culture, language and songs.

Siva regularly promotes the Serrano language online and with the linguists from San Manuel, who are part of the Serrano Language Revitalization Project, an effort aimed at resurrecting the language. Although Araujo-Levinson is a natural speaker when it comes to Serrano, Siva thinks that one day he’ll lose his star pupil to mathematics.

“We’d hate to lose him,” Siva said. “He’s just one of those talents. It’s great to see him teaching it. Teaching it is so important now.”

Siva recalled his aunt telling a story of how her grandfather was once approached by a neighboring tribal community, who admitted it had lost its songs to honor the dead. It was a humbling experience, she said, and Morongo offered to teach the community the Serrano songs.

He explained that the songs are from the creator and meant for all of God’s children. But the experience left an impression on the family — especially on him, Siva said.

“My great-grandfather told his family: ‘You have to remember your culture and language, or else you’ll be left a wandering tribe.’”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.