‘Beverly Hills while Black’: Race, wealth, policing collide on Rodeo Drive

Salehe Bembury was walking away from the Versace boutique on Rodeo Drive last fall when a Beverly Hills police officer stopped him for jaywalking, told him to put his hands behind his back and asked if he was carrying a weapon.

“Don’t want to mess up those shoes; those are pretty nice,” the officer remarked as he asked Bembury to spread his feet and patted him down, body camera footage released by the Beverly Hills Police Department shows.

The young Black man being frisked hadn’t just been shopping at the luxury store. He was then the vice president of sneakers and men’s footwear for Versace.

As he was being searched, Bembury said that he had designed the shoes in his shopping bag. He told the officers they were scaring him because of “the climate that we’re in,” then started recording on his cellphone.

“I’m getting f— searched for shopping at the store I work for and just being Black,” Bembury said into the camera, holding up the Versace bag.

Bembury captioned his video on Instagram: “ BEVERLY HILLS WHILE BLACK. I’M OK, MY SPIRIT IS NOT.”

Ninety people were arrested by the unit. Eighty of them were Black, four were Latino, three were white, two were Asian and one was classified as “other.”

It was the kind of encounter that Black visitors to Rodeo Drive call a sad — and totally unsurprising — reality in the opulent shopping corridor famed for its ultra-high-end boutiques, celebrity shoppers a la Kim Kardashian, and ubiquitous Lamborghinis and Ferraris.

“Just being Black, you always get followed,” by police or store employees, said Nate Weston, a 28-year-old clothing line founder and professional fighter from Atlanta who was shopping along Rodeo Drive last week with a pair of Versace sunglasses hanging from his shirt. “It’s expected that you don’t have money.”

In the case of Bembury, who could not be reached for comment, he was not charged, and no citation was issued, a city spokesman told The Times.

Rodeo Drive is a place that feels, at once, elite and off-limits. Security guards in black suits stand in doorways of luxury shops, and employees meet potential customers outside, asking if they have appointments. Shoppers walk briskly with bags from Prada and Dolce & Gabbana. Window-shopping tourists crowd around Rodeo Drive street signs for selfies, and the TMZ Celebrity Tour bus rolls through every so often.

In the Gucci flagship store, a navy blue women’s cashmere cardigan sells for $2,100, and a red toddler’s T-shirt with a teddy bear goes for $225. In the Versace store, a pair of pink fuzzy slippers fetches $525.

Wealth and race have long collided in Beverly Hills — a city that is 78% white and that for decades had restrictive covenants barring Black and Jewish people from owning homes.

Last year, demonstrators descended on Rodeo Drive to protest the police murder of George Floyd. Organizers said Beverly Hills, along with other upscale areas, was deliberately chosen because it was a symbol of white affluence.

Beverly Hills officials were criticized for insisting on charging peaceful protesters organized by a group called Black Future Project — even as prosecutors for the city and county of Los Angeles declined to prosecute demonstrators elsewhere for similar minor infractions like violating curfews and dispersal orders. The Beverly Hills charges were dropped this spring after a judge ruled that an emergency ordinance the city used to make the arrests was unconstitutional.

Now, Beverly Hills is being sued over allegations that its Police Department illegally targeted Black people in 2020 and 2021, arresting them at disproportionate rates and using excessive force for minor infractions.

“Beverly Hills, do you want Rodeo Drive to be known as a street where no Blacks are allowed? Is that where we’re headed?” Benjamin Crump, a prominent civil rights attorney, asked during a news conference last week.

At the time Bembury was stopped near Rodeo Drive in October 2020, the Beverly Hills Police Department had a special unit patrolling the tony street. According to police, the shopping corridor had experienced a rise in thefts, people spending money obtained by defrauding the state’s unemployment system and “quality of life” complaints about loud music and marijuana smoke.

The Times reported last week that the Police Department’s Rodeo Drive Team, which operated from August through October 2020, arrested 90 people. Eighty of them were Black, according to the department’s figures obtained under a California Public Records Act request.

Police have not explained why Black people were targeted to such a degree. Few have been charged.

Crump — who has represented the families of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor and others killed by police — and attorney Bradley Gage are seeking class-action status for the lawsuit filed in August alleging brazen racial profiling by Beverly Hills police. (The lawsuit describes Bembury’s stop, but he is not a named plaintiff.)

Among the named plaintiffs are Jasmine Williams and Khalil White, a Black couple from Philadelphia who were jailed last summer after getting stopped for riding scooters on the sidewalk off Rodeo Drive.

Williams, 30, told The Times that she and White, her boyfriend, were on vacation and that she had previously visited Rodeo Drive, where she was drawn to “the environment, the nice shopping malls, how it looks.” They “were having the time of our lives” before police stopped them on the scooters and asked for identification, which they did not have.

In a statement, the Police Department said the couple had been “warned earlier that day that riding a scooter on the sidewalk in Beverly Hills was prohibited.”

Williams said a mostly white crowd formed as they were being arrested, filming with their cellphones. She screamed the phone number of a friend, asking bystanders to contact her and let her know what was happening.

Williams, a nurse, was jailed for 12 hours, and White was jailed for two days, Gage said.

White was charged in Los Angeles County Superior Court with resisting arrest and falsely identifying himself to police. Williams was charged with falsely identifying herself to police. The charges were dismissed in February, records show.

“To go from being on vacation to being in a jail cell was the worst feeling ever,” Williams said. She would have been merely annoyed if she had gotten a ticket, she said, but she will never forget the arrest and will likely never return to Beverly Hills.

Cynthia Harris, a 53-year-old Black social worker who lives in View Park, said allegations that police in Beverly Hills targeted Black people are hardly surprising. She is still traumatized by a police stop there three decades ago.

When she was in her early 20s, Harris and a friend, a young Black man, had just left a late-night diner in his sporty two-seater car and were driving down Rodeo Drive. Two white police officers pulled them over and drew guns on her friend, Harris said.

She said officers at first asked if she was OK, then told her to be quiet and get out of the car when she asked why they were stopped. Officers searched the car as she and her friend sat on the curb, then let them go, she said.

Beverly Hills Police Chief Sandra Spagnoli announced her retirement Saturday, ending a rocky tenure for the city’s first female top cop that was marked by more than 20 lawsuits or claims of misconduct.

“At first, I thought it was my safety, that they were worried about me ... it came to my mind years later that they had no reason to pull us over,” Harris said. “I definitely think it was racial profiling because he was a young Black man in a sporty car.”

She has no issues in upscale places like Beverly Hills and Brentwood now, as a mother toting around her children. But “the anxiety is still there whenever cops get behind me. I get nervous. I want to make sure I have everything in place. My license. My registration.”

In October 2020, Beverly Hills expanded its police force from 145 to 150 full-time sworn officers, citing the enforcement of pandemic rules; a crackdown on unemployment fraud; and “large-scale civil unrest and ongoing protests,” including those anticipated during the presidential election.

“We’re one of the few cities in the country that not only didn’t defund police; we increased them,” said Todd Johnson, president and chief executive of the Beverly Hills Chamber of Commerce. That is a point of pride, he said, and merchants and shoppers appreciate the high security and fast police response times.

Last year, he said, many luxury shops added private security guards. There are also more than 2,000 cameras throughout the city, he said, and “you’re not going to get out of here without being seen, whether it be walking or license plate recognition.”

Beverly Hills, he said, is “not targeting African Americans; we’re targeting people that commit crimes.”

Business has been booming this year after the pandemic slowdown, and international visitors are starting to return as travel restrictions ease, Johnson said.

Rodeo Drive shoppers, he said, include extremely wealthy people who fly in on private jets just to shop, Beverly Hills residents and tourists who have seen the famed corridor on television.

“You can’t experience luxury through the internet,” he said. “You can buy a nice item, but you don’t experience pulling up to Gucci, getting handed a glass of champagne, having a private shopper walk through there with you, trying on things.”

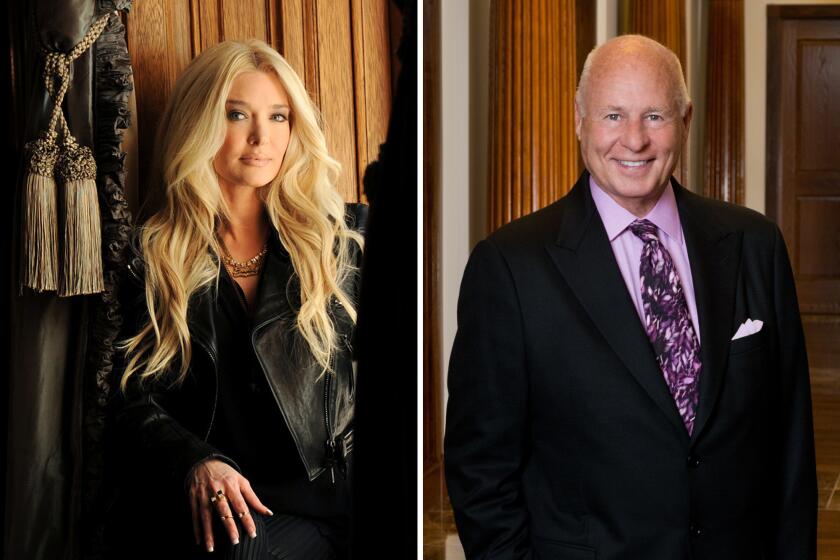

Tom Girardi is facing the collapse of everything he holds dear: his law firm, marriage to Erika Girardi, and reputation as a champion for the downtrodden.

It’s that luxury vibe that draws DeAngelo Davis to Rodeo Drive every few weeks to soak in the atmosphere.

Davis, who is 24, Black and lives in Hollywood, was walking through stores with two friends last week, fantasizing about the things they would buy if they were rich. He especially likes the Salvatore Ferragamo store and wants to buy a pair of shoes from there — someday.

He said that, as a young Black man, he is used to being eyeballed around the luxury shops, and he has noticed police paying close attention to lines outside the Gucci store when they have more Black people in them.

“You think, ‘I’d better not do anything,’” Davis said. “You expect it in places like this, in higher-end places.” He joked that he should carry around an empty shopping bag even when he’s just browsing, just so stores take him seriously as a potential customer with money.

His friend, Destiny Toli, a 26-year-old Black woman who lives in East L.A., said, “They always assume Black people are here to window shop.

“And the first thing they do when something goes missing is to go to the people who aren’t buying things,” Davis said.

Davis and Toli were showing their friend, Tinashe Mukoyi, from Bismarck, N.D., around Rodeo Drive. Mukoyi, 25, who is also Black, started designing clothes during the pandemic and was wearing a T-shirt with his logo written in purple cursive.

Mukoyi calls his brand Mkoi Apparel and wants it to evoke a “youth sense of royalty,” he said.

“In life, you yourself determine your own royalty,” Mukoyi said. He had spent the afternoon admiring the clothing in the luxury stores on Rodeo Drive, drawing inspiration from different fabrics and color patterns, and could not stop smiling.

“I can see my store being here,” he said. “Someday.”

Times staff writer Matthew Ormseth contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.