Trial begins for L.A. County deputy accused of manslaughter in 2016 shooting

When Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Deputy Luke Liu opened fire on a vehicle in Norwalk in February 2016, the shots didn’t reverberate far beyond the parking lot where he drew his weapon.

There were no protests in the wake of Francisco Garcia’s death that evening. No public demands for prosecutors to intervene. No dramatic video to stoke debate about Liu’s deadly decision.

Few had heard of the case when then-Los Angeles County Dist. Atty. Jackie Lacey filed manslaughter charges against Liu in December 2018, describing the deputy’s choice to shoot into Garcia’s car as he drove away as “unjustified and unreasonable.”

Now, Liu’s case could be a litmus test of juries’ willingness to convict peace officers in the wake of a national reckoning on the way police use force, as he becomes the first law enforcement officer to stand trial for an on-duty shooting in L.A. County in more than two decades.

Opening arguments in Liu’s manslaughter trial began Wednesday afternoon, and to some observers, the fact that the case will see the inside of a courtroom when so many other controversial shootings have not is a landmark on its own.

As shootings by officers go, the killing of Francisco Garcia at a Norwalk gas station in 2016 spurred little media attention or street protesting.

“Over 1,500 shootings by officers with no charges,” said Miriam Krinsky, a former federal prosecutor and L.A. County Sheriff’s Department watchdog who now serves as executive director to a national network of progressive prosecutors. “So, the fact that we do have a case where charges were pursued, where there is an endeavor to hold someone who wears the badge accountable in an on-duty shooting, is significant.”

Liu was on patrol on Alondra Boulevard, near the border of Cerritos and Norwalk, when he pulled into a 7-Eleven parking lot to investigate an Acura Integra that had been reported stolen. When Liu approached Garcia to ask who owned the vehicle, Garcia replied, “It’s none of your business,” according to a Sheriff’s Department report.

Liu walked to the back of the car, then started moving to the driver’s side, according to court records. At that point, Garcia began driving away at a slow speed. Liu claimed that the vehicle struck his knees and that he saw Garcia reaching for something, records show. Fearing Garcia was trying to retrieve a weapon, Liu began shooting.

The deputy fired at least seven rounds, hitting Garcia four times, a medical examiner said at a 2019 preliminary hearing. Liu tried to perform life-saving measures after the shooting, but Garcia died a short time later.

During his opening statement Wednesday, Deputy Dist. Atty. Christopher Baker said Garcia posed no threat to Liu or public safety, noting he was driving so slowly that Liu was able to keep up with the car on foot. The shooting was not only unnecessary, said Baker, but it was reckless.

“He fired wildly at Garcia, killing him, and endangering the lives of innocent people who were sitting at the stoplight in the deputies’ line of fire,” Baker said.

At the preliminary hearing, several witnesses refuted Liu’s claim that he was struck by the vehicle. Garcia was not armed, and no gun was recovered at the scene. Liu also indicated that he knew Garcia was unarmed while he was performing CPR, according to the testimony of a Cerritos College campus police officer who responded to the scene.

Baker said Liu told paramedics he’d suffered injuries to his knee, thighs, head and neck as a result of being struck by the car. But doctors at a Long Beach emergency room said the deputy was not injured, according to Baker.

Defense attorney Michael Schwartz, who has won acquittals for police officers in a number of high-profile use-of-force cases, argued Wednesday that Liu had worked nearly 16 hours straight before the shooting and criticized sheriff’s investigators for asking him to give a statement when he was exhausted and traumatized following the incident.

A homicide had occurred in the same gas station the night before, according to Schwartz, who said the deputy had reason to be on high alert and fearful that Garcia had a weapon.

“He wasn’t sure if this person he was contacting who had stolen a car … was maybe a gang member who was coming back, in his words, to pay homage to his brethren or get revenge,” Schwartz said.

Unlike other high-profile cases that have resulted in police facing prosecution in shootings in recent years, there is no jarring video of Garcia’s death. Surveillance cameras at the gas station only captured parts of the encounter, and none of the footage clearly shows Liu opening fire. The recordings also lack audio, and Schwartz noted during his opening argument Wednesday that the footage was subject to any viewer’s interpretation.

Liu’s tactics were at odds with the policies of most major city law enforcement agencies, which warn officers against shooting at moving vehicles when the driver is otherwise unarmed, even if they are attempting to ram an officer. Most tactical experts say standard police service weapons are unlikely to stop a car, and if a shot does disable a driver, that only succeeds in turning the car into a deadly weapon.

When two undercover California Highway Patrol officers opened fire on a moving vehicle in Fullerton this weekend, they used a tactic that federal authorities and law enforcement experts consider dangerous and has been banned by police leaders in Los Angeles, New York and several other major U.S. cities Law enforcement experts say there’s a simple reason why many agencies bar officers from shooting at moving cars, even if drivers appear to be attempting to ram them: Police service weapons are unlikely to stop a speeding vehicle, and firing a barrage of rounds might only serve to increase the danger faced by officers and bystanders if the driver is shot and unable to control the car.

Baker said Wednesday that Liu’s actions were against Sheriff’s Department policy.

Liu had been a deputy for about 8½ years at the time of the shooting, Schwartz said. Both the Sheriff’s Department and Schwartz declined to comment on his status with the agency Wednesday. In a statement, the Sheriff’s Department said it had “faith in the criminal justice system” and would not offer any comments on the trial until its conclusion.

The charges against Liu initially sparked outrage among deputies, many of whom lined the courtroom during an arraignment hearing in 2016. The union representing rank-and-file deputies also issued a statement of support for Liu after he was charged and accused Garcia of being under the influence of methamphetamine at the time of the shooting.

On Wednesday, however, Liu’s case began before a nearly vacant gallery and a union spokeswoman did not respond to a request for comment from The Times.

While Lacey filed the charges, Liu’s case could also forecast how L.A. County Dist. Atty. George Gascón will fare in his mission to hold police officers accountable in use-of-force cases. Gascón has already filed charges this year against a Torrance police officer and a Long Beach school security guard in separate shootings, and the Long Beach case is very similar to the one brought against Liu.

In years past, prosecutors and legal observers often listed concerns about a jury’s willingness to convict a police officer among reasons not to bring charges in an on-duty shooting. But Gascón was elected on a platform heavy on police accountability after a summer that saw tens of thousands of people flood streets in Los Angeles and across the nation in the wake of George Floyd’s murder by a Minneapolis police officer.

Schwartz acknowledged the “landscape” of such cases has changed, but said he ultimately didn’t believe societal forces would affect the outcome.

“This case, like any case, has to be tried in a court of law. Not in a court of public opinion,” he said in an interview. “If past cases have taught us anything … what’s in the media is rarely the entire story, or even an accurate story and accurate picture of what actually happened.”

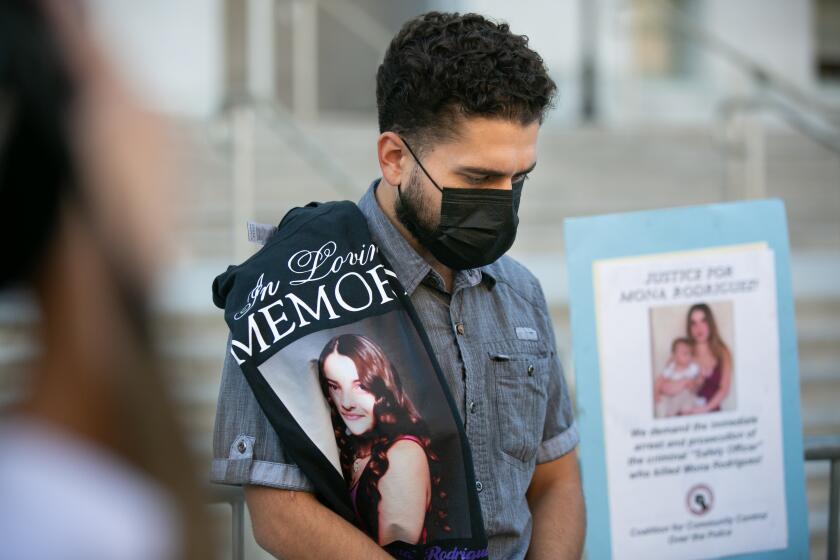

Long Beach school safety officer Eddie F. Gonzalez charged with murder in the shooting death of Mona Rodriguez.

Schwartz expects about a dozen witnesses to be called by both sides, but would not say if Liu planned to take the stand in his own defense.

If convicted, Liu faces up to 11 years in prison. He was originally also charged with a gun enhancement that could have added up to a decade to his sentence, but the special allegation was dropped from the case last December shortly after Gascón announced his policy barring the use of sentencing enhancements.

Krinsky said she believes a conviction could have a significant impact on police officers’ behavior in California in the future, but hoped the mere sight of Liu seated at the defense table would send a message to L.A. County residents that law enforcement officers will face consequences if they act recklessly.

“At the end of the day, what we want and expect are D.A.s who are going to look at the facts and treat those who wear the badge no more favorably than anyone else and try to remove emotion from the decision,” she said. “If we’re going to restore public trust in law enforcement, we need to be willing to bring these cases to a jury.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.