Massive undersea mountain named after famed UC San Diego oceanographer Walter Munk

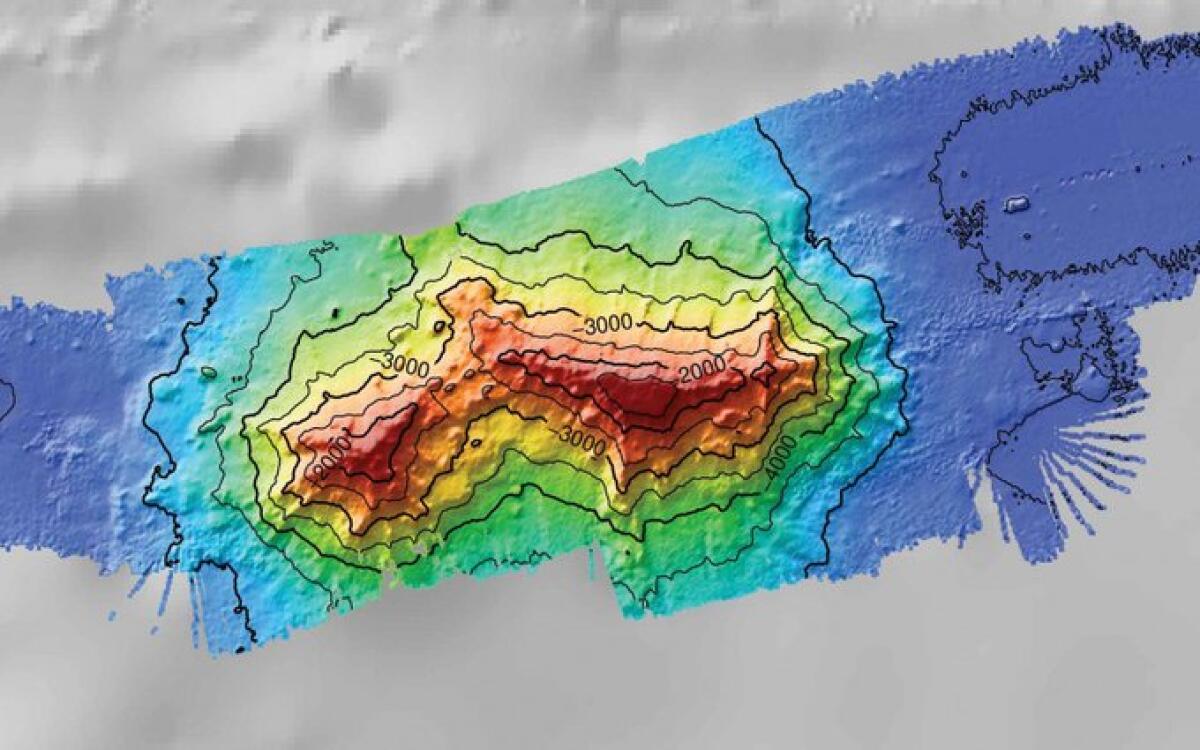

The mountain is in water more than 3 miles deep, and it has a diameter of roughly 22 miles — the distance between San Diego and Solana Beach

San Diego — An underwater mountain in the Pacific that is taller than the highest peak in Southern California has been named in honor of Walter Munk, the late UC San Diego oceanographer whose grand insights led many scientists to call him the “Einstein of the oceans.”

The 12,477-foot seamount was picked up on sonar by the UCSD research ship Sally Ride two years ago as it cruised 1,100 miles west-southwest of Hawaii, not long after Munk died at the age of 101.

Sonar revealed that the ship, led by geophysicist David Sandwell, one of Munk’s colleagues, had discovered a massive guyot, a sub-sea mountain with a flat top.

The mountain was in water more than 3 miles deep, and its top was more than 4,000 feet below the surface, in darkness. It has a diameter of roughly 22 miles — the distance between San Diego and Solana Beach. The highest peak in Southern California is San Gorgonio Mountain at 11,499 feet.

“It was so huge,” said Sandwell, a researcher at UCSD’s Scripps Institution of Oceanography. “We wanted to name it after Walter because we loved him.”

Walter Munk, the high-spirited scientist-explorer whose insights about the nature of winds, waves and currents earned him the nickname the “Einstein of the Oceans,” died Friday in La Jolla.

The International Hydrographic Organization approved the name earlier this year. UCSD just made the announcement, timing it to Munk’s birthday about a week ago.

Munk was one of the most esteemed oceanographers of the 20th century, based on work he did at Scripps Oceanography. Scripps became his home shortly before the start of World War II, when he was a graduate student.

He began performing research on behalf of the Navy and soon developed far better ways to forecast surf conditions. Munk’s research helped allied forces fine-tune their landing at Normandy for the D-Day invasion, saving lives. His wavecasting and weather research also helped captains guide their ships more safely in the open ocean.

After the war, Munk helped create and lead a series of deep-sea expeditions that profoundly changed how scientists think about everything from oceanic currents to the composition of the seafloor to the presence of marine life miles below the surface. That made him one of the leaders of the so-called golden era of ocean exploration in the 1950s and ‘60s.

Munk built upon that work throughout his life and expanded into areas like climate change.

Much of his work involved a combination of logic and chance — which also was involved in Sandwell’s discovery of the seamount.

Satellite imagery of the surface of the Pacific suggested that there might be sub-sea mountains in a specific area of the Pacific. Sandwell persuaded the leaders of the R/V Sally Ride to briefly visit that area in 2019 as the ship was sailing between Hawaii and Guam.

The side trip and additional research revealed that the mountain exists on an area of crust that is at least 117 million years old. Over the years, the crust sank as it shifted away from heat sources, causing the seamount to progressively slip beneath the ocean’s surface,

“There wasn’t much time to do this research, but we (Scripps) nailed it,” said Bruce Applegate, who oversees the university’s fleet of research vessels.

“The slopes of the mountain don’t appear to have the same vertical relief of Mt. Whitney. But the mountain is majestic.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.