History forgot the 1871 Los Angeles Chinese massacre, but we’ve all been shaped by its violence

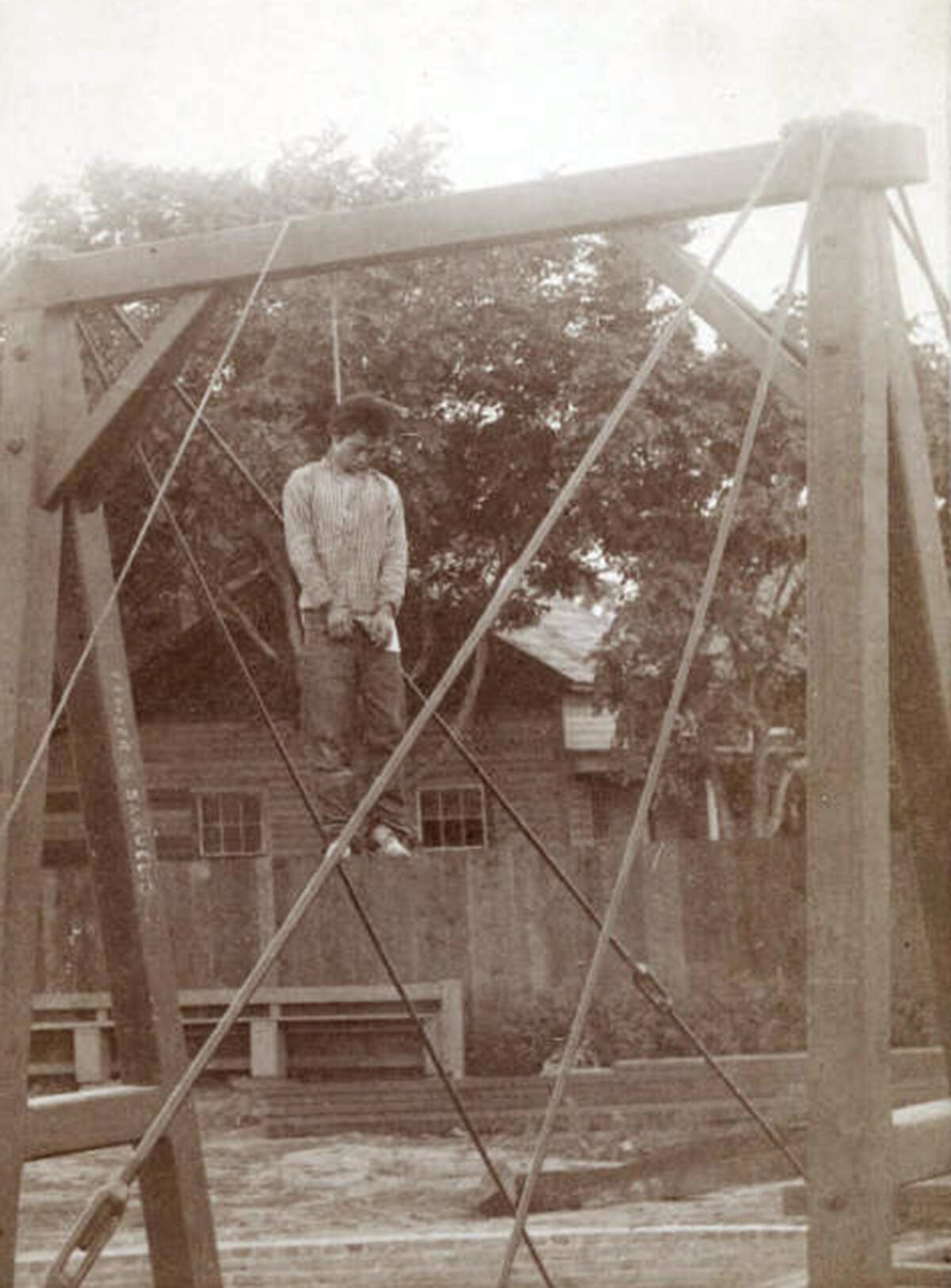

On this day 150 years ago, a largely white mob of hundreds descended upon what’s now downtown Los Angeles and indiscriminately began beating, shooting and hanging any Chinese person they saw.

The 1871 Los Angeles Chinese massacre resulted in the deaths of 18 Chinese men and is believed to be the most lethal example of racial violence ever recorded in the city. It was quickly and eagerly forgotten.

City leaders, embarrassed that the frontier town had made national headlines for violence and lawlessness, built up the police department and tried to restore the rule of law. Eight of the attackers were tried for the crimes but eventually released, and a small indemnity was paid to the Chinese government as an apology. Calle De Los Negros was bulldozed and redeveloped. The Chinese community was rebuilt in a different location.

A century and a half later, as Asian Americans are facing a surge in racial violence prompted by the pandemic, I’m thinking about the lessons never learned from this forgotten history.

The massacre was buried so deeply that even those with deep roots in Chinatown did not know it happened until generations later. Gay Yuen, who was born and raised in Los Angeles’ Chinatown and even taught Chinese American history, didn’t learn about it until she retired and joined the board of the Chinese American Museum.

The city’s first Asian councilman, Michael Woo, whose family helped found Chinatown, learned about it nine years ago, in 2012, when he was asked to review a book on the massacre. There was no memorial until 2001, when a small plaque was installed. In the 150 years since, no relatives of survivors have come forward, and there are no eyewitness accounts.

But perhaps that’s unsurprising. One measure of the success of a campaign of racial terror is the fearful silence that follows.

“This was an ethnic cleansing,” said Gabriel Chin, a law professor at UC Davis who has studied anti-Chinese legislation. “And it was successful.”

The Los Angeles massacre was just one part of a decades-long campaign of anti-Chinese violence and racism, and it wasn’t even the most lethal: In Rock Springs, WY in 1885, at least 28 Chinese miners were slaughtered by a group of white miners who blamed them for economic struggles.

Beth Lew-Williams, a Princeton history professor and the author of the book “The Chinese Must Go,” found that between 1885 and 1887 there were 86 killings of Chinese people and more than 168 forced or attempted evictions of Chinese communities. It’s impossible to know the true scale of the violence, which went unchecked for nearly a half-century.

The massacres, forced evictions, and the constant threat of white violence against Chinese people helped pressure politicians into passing an entire system of laws excluding Asian Americans from doing business, owning land and competing for the same opportunities that white men wanted. Chinese Americans were demonized as dirty, disease-ridden, and deemed an existential economic threat. It was a half-century of racial violence that prompted the Chinese Exclusion Act and laid the groundwork for Japanese incarceration during World War II.

It’s a history that feels uncomfortably familiar to us in 2021. The economic tensions may be different, but the stereotypes are the same. Asian Americans are still seen as perpetual foreigners and economic threats. And the violence is on the rise: The STOP AAPI Hate tracker has recorded more than 9,000 incidents of anti-Asian violence since the pandemic began in 2020. In Los Angeles County, anti-Asian hate crimes soared 76% last year.

It’s hard to measure how a forgotten history has affected us without speculating.

In Los Angeles, there’s a certain generation of Chinese Americans that grew up feeling distanced from their culture. Their parents raised them to speak perfect, accentless English, encouraged them to fit in and prevented them from learning Chinese for fear of racism. They were guided into professions in science, economics and medicine that they felt would be insulated from racial discrimination. They learned to keep their heads down and endure racism, because justice was not guaranteed. Did their parents remember the massacre?

The cultural distance of one generation was echoed and magnified in the next, and many Asian Americans today still have fraught relationships with their culture. Could this be counted as part of the massacre’s legacy?

During my reporting in Chinatowns across the country, I’ve encountered tough, crusty old men and women with uniquely cynical world views and a belief that nothing is more important than survival and economic success. Are these attitudes in some way shaped by memories of violence and discrimination?

There are no definitive, comforting answers. The most enduring legacy of America’s era of anti-Chinese violence is simply an absence of Chinese people and communities where they once were. A group of community leaders and Chinatown elders are partnering with the city of Los Angeles and the Chinese American Museum to create a proper memorial to the victims beyond the small plaque currently installed.

When the 1871 Chinese Massacre finally finds its place in history, I hope history will also include what happened after the violence.

The Chinese community did not simply accept their fate. They demanded restitution and sued for damages, though unsuccessfully. At least 14 out of 15 total Chinese laundrymen in Los Angeles refused to pay their city business license fees the year after the massacre, in what may be the first example of Chinese American civil disobedience. According to accounts of the time, some Chinese Americans responded by taking even more pride in being Chinese, displaying their culture even more boldly despite the danger.

It took them 10 months, but the few Chinese Americans in Los Angeles at the time raised the $8,000 to pay for proper burial ceremonies — an unimaginable amount of money for a group of poor immigrants at the time.

They recruited a priest, built an altar at the site of the massacre, made offerings and burned incense. From there, they marched on foot to the city graveyard to lay the victims to rest.

Though the massacre was forgotten by history, on this the record is clear: the 18 men who died mattered very much to their fellow Chinese Americans in Los Angeles.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.