Diamond Mendoza rolled up the sleeve of her shirt — a yellow tee decorated with an exuberant rendering of the Mona Lisa — to show the scars of abscesses that had been lanced and healed.

She wants to get off heroin, which she first turned to decades ago after a heartbreak. She wants to get a certificate to prove herself to employers, maybe become a phlebotomist or a nurse. She relishes the idea of handing over that paper and saying, “Hey — I may be a drug user, but I got a certificate.”

But above all, Mendoza said, “I hope to live longer.”

Deaths from drug overdoses have surged during the pandemic, claiming more than 90,000 lives last year across the country, according to federal data. As the numbers have soared, many experts, advocates and lawmakers have promoted an idea still fresh to the United States: giving people a safe place to inject drugs under supervision.

In California, it would be the most dramatic step to date for government and health officials in pursuing the philosophy of harm reduction, which seeks pragmatic ways to reduce the harmful effects of drug use. The idea was shot down three years ago by Gov. Jerry Brown, who vetoed a bill to try out such sites in San Francisco and said that “enabling illegal and destructive drug use will never work.”

Now state Sen. Scott Wiener (D-San Francisco) and other lawmakers are pushing to allow San Francisco, Oakland and the city and county of Los Angeles to approve entities to run such programs. The latest California bill, SB 57, envisions them as “a hygienic space supervised by trained staff” where people can use “preobtained drugs,” get sterile supplies and connect to treatment for substance use disorder.

When Melvin Latham heard about the idea being aired in Sacramento, it sounded like an impossible dream. A safe, supervised place to do drugs? A staffer there to save someone who overdosed?

“That’s something out of a movie or something!” Latham said, leaning back in disbelief.

Scores of “supervised consumption” or “safe consumption” sites exist legally around the globe, including in the Netherlands, Germany and Canada. Such programs have been credited with preventing deaths, reducing the risk of HIV and other infectious diseases, and cutting back on public nuisances and hazards such as discarded needles.

In L.A. County, health officials are enlisting people living in tents, RVs and makeshift shelters to help get unhoused people vaccinated.

In Switzerland, researchers found that the facilities helped reduce deadly overdoses and cut back on drug use in public places. In the U.S., researchers found that one unsanctioned site at an unrevealed location had overseen more than 10,000 injections over five years. There had been 33 opioid-related overdoses in that time — all of them reversed with medication by trained staff.

“There isn’t an increase in crime in the neighborhood where the site is located. There has not been a single death from anyone having an overdose at the site,” said Peter Davidson, an associate professor in the UC San Diego Department of Medicine who helped evaluate the program. “It generally seems to be good for public health and social order outcomes, in the same way that it does elsewhere in the world.”

The California bill has drawn opposition from groups including the California Narcotic Officers’ Assn., which argued that “rather than a robust effort to get addicts into treatment, SB 57 alarmingly concedes the inevitable and immutable nature of drug addiction and abuse.” It pointed to a contested report from Alberta, Canada, that raised concerns about police calls, needle debris and overdose deaths near such sites.

Creating such sites “only promotes drug consumption,” said Shaun S. Rundle, deputy director of the California Peace Officers’ Assn., another group opposing the bill. “We prefer a push to resolve dependency rather than facilitate it.”

Jeannette Zanipatin, California State Director for the Drug Policy Alliance, countered that “what we’re currently doing is not working.” She argued that besides preventing overdoses, such sites can build trust to support people when they do want to pursue treatment. Healthcare providers and advocacy groups such as the California Society of Addiction Medicine have backed the proposal, along with the local jurisdictions that would host the new sites.

Researchers with the Rand Corp. Drug Policy Research Center pored over published research on supervised consumption sites and found it was “almost unanimous in its support, but limited in nature.” Center director Beau Kilmer said “there seems to be little basis for concern about adverse effects,” but the bulk of the studies don’t have a “credible control group” to gauge if results are caused by the facilities themselves.

“It’s well past time that we start piloting supervised consumption sites in the United States and learning from them,” Kilmer said, including assessing how they affect referrals to treatment.

Latham, 43, lives in a downtown tunnel near Bunker Hill. He and Mendoza look out for each other, but he said that for anyone doing drugs outside, “you’re constantly looking over your shoulder,” worrying about someone trying to harass or hurt them.

Then there’s the threat of fentanyl, a powerful opioid that has felled many people using drugs, including some who had no idea they were taking it. L.A. County officials have tied the synthetic opioid to a surge in overdose deaths among homeless people in recent years. Latham and Mendoza said they tried to steer clear of fentanyl because of its potency, but it often is mingled with other drugs.

“One person is here, next thing you know he’s gone,” Latham said of the deaths in downtown L.A. “It’s really scary.”

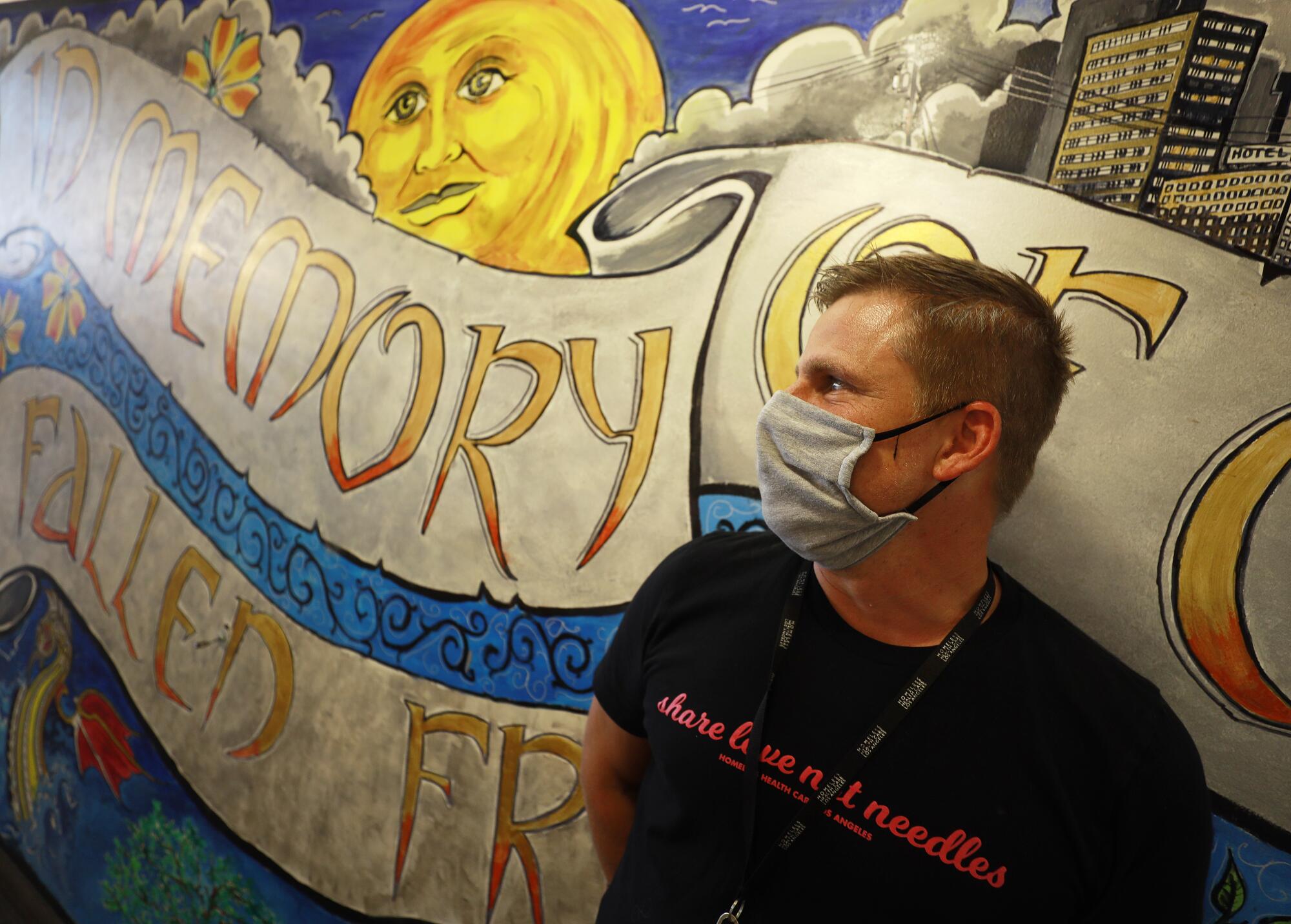

In Los Angeles’ skid row, Darren Willett imagines that if it were allowed, the Center for Harm Reduction could set up cubicles for people to inject their drugs under supervision, then let them hang out in another room under the watchful eye of staff.

“There would be no such thing as an overdose” death, said Willett, director of the center, which is operated by Homeless Health Care Los Angeles. “The No. 1 reason people are dying from drug overdose is using alone. And why are they using alone? Because it’s criminalized and stigmatized.”

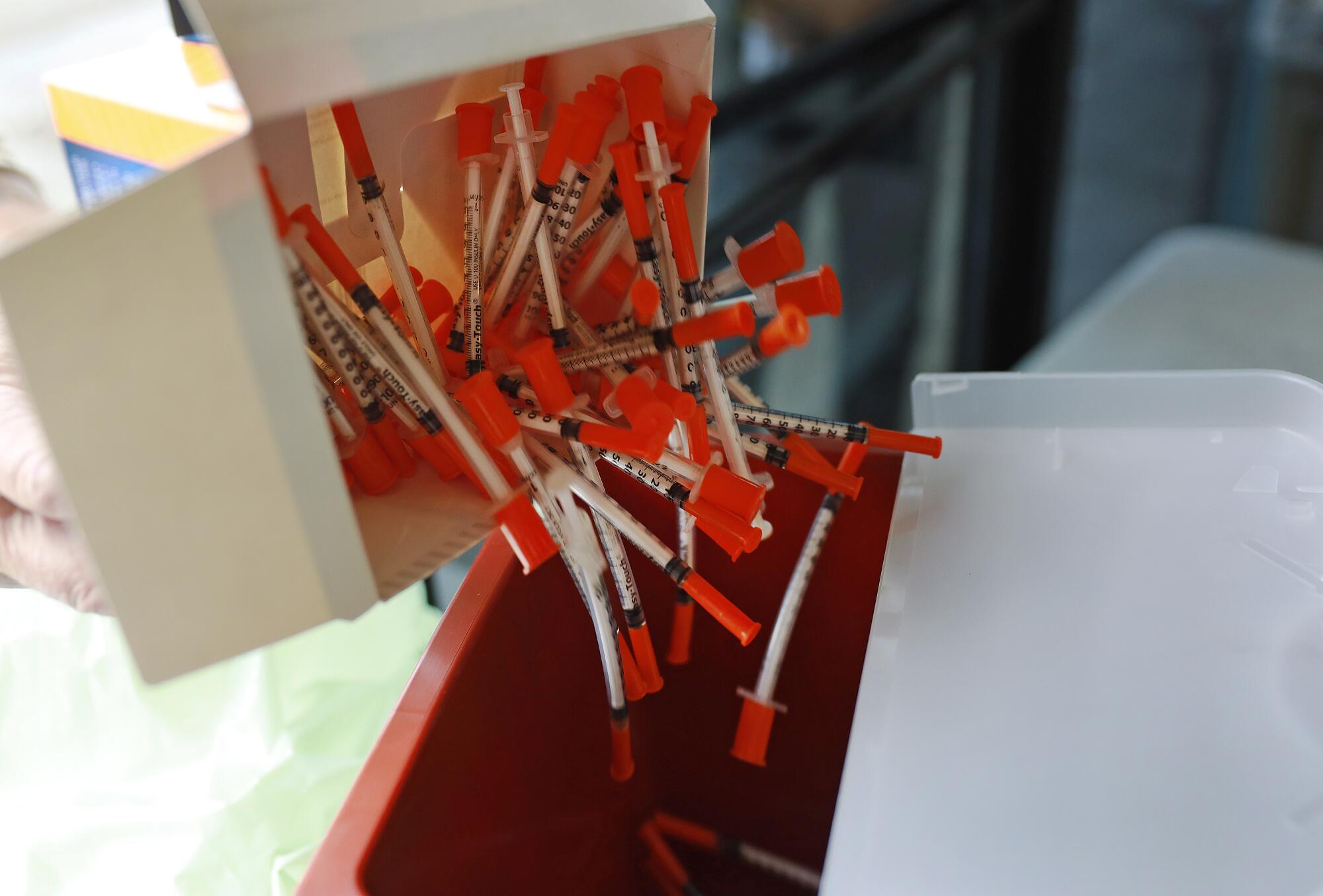

Instead of demanding that people stop using drugs, the Center for Harm Reduction tries to help them be safer and healthier. It offers up clean needles to help people avoid infections from sharing syringes. It hands out Narcan — naloxone spray that can pull someone out of an overdose — so that people can save lives on the streets.

It teaches people how to inject themselves as safely as possible to avoid infections and collapsed veins. And physicians on site provide medications such as suboxone to help people manage their cravings, avoid withdrawal, or potentially reduce or abstain from opiate use if that is their goal.

The center helps people who are trying to quit drugs, but its goal is to make them safer whether or not they are using. On a recent weekday, a small board near its doors bore the quotation, “50% of something is better than 100% of nothing.”

When a man careened on his bicycle up to the doors of the center, where folding tables had been set up to form a makeshift window, harm reduction specialist Arlene Lemus asked brightly, “What can I get for you, sir?”

Her shirt bore the slogan “WE LOVE DRUG USERS.” Before she picked up a brown bag of syringes, alcohol wipes, sterilized water and other “safe injection” supplies, she asked, “Your drug of choice?” to make sure she provided the right kind of syringe. Using something too large could unnecessarily damage veins, Willett explained.

Another man approached the doors and asked, “Is there any extra Narcan?”

Lemus said yes and asked about the doses he had picked up before. The center tries to keep track of where and how often the medication is used to thwart overdoses, marking reversals with blue pins on a downtown map. The pins form a blue swarm over skid row, pocked with red pins marking deaths.

“I took ‘em to the tent city that I usually use at,” the man told her. “One guy used while I was there. I saved somebody’s life.” He began to run through the details, then remembered another incident.

“That’s two I saved,” he said.

Willett said it is one of the main ways the center measures its success: “Can we keep them alive?”

Recently, the skid row center has been preparing to open its “drop-in center” after more than a year and a half of limiting access amid the pandemic. Just before COVID-19 struck, it had finished a new room in back — a tranquil, welcoming space with cots and beanbags to lounge on, computer terminals, and outlets for people to charge their phones. Willett said the soothing room, with its abstract paintings and cascading artificial vines, was modeled after an injection room in Copenhagen.

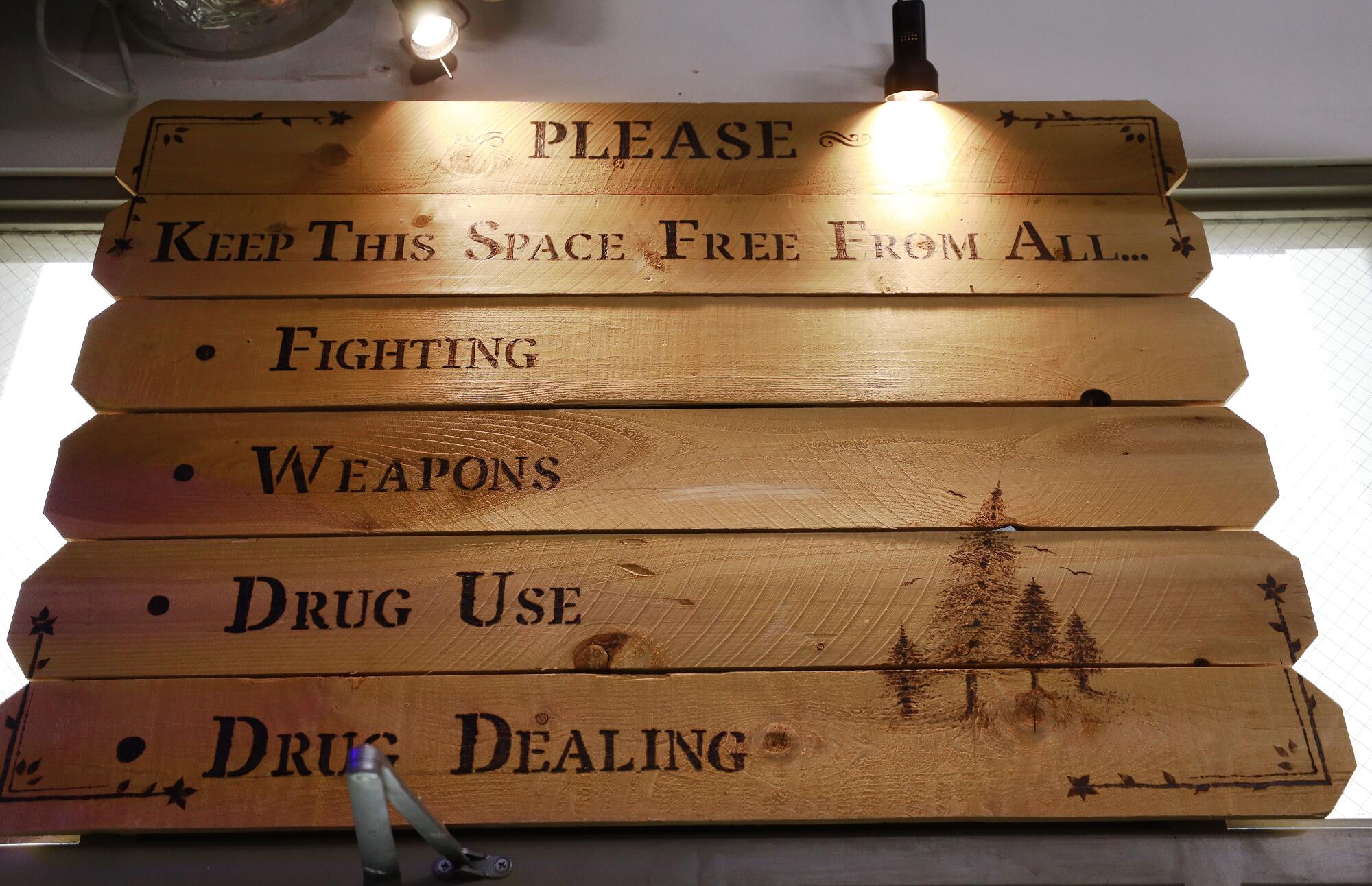

This isn’t a consumption room, and legally it cannot be. A wooden sign overhead asks people to refrain from drug use. But Willett imagines that if such supervised sites were legalized in California, a room like this mellow space that hosts art and poetry classes could become a safe place for people to be monitored after injecting themselves in clean cubicles or smoking in rapidly ventilated rooms.

When the center surveyed more than 500 people who use drugs about whether they would use such a supervised consumption facility, the vast majority said yes, according to data provided by Willett. The majority said they would do so regularly — at least a few times a week if not daily.

When Brown vetoed supervised consumption sites three years ago, he called the idea “all carrot and no stick” and warned that even if California gave its blessing, it couldn’t immunize the facilities from federal prosecution. Earlier this year, a Philadelphia nonprofit that aspired to open a safe injection site was thwarted in court.

The motives of the Safehouse nonprofit are “admirable,” the 3rd Circuit Court of Appeals stated in its ruling. “But Congress has made it a crime to open a property to others to use drugs. And that is what Safehouse will do.”

Willett said he would personally be willing to get arrested for the cause, but he worries about putting others at the center at risk. As it stands, the skid row center has hesitated to offer “drug checking” — testing drugs to check their chemical content and make sure users know what they are taking — because of legal concerns.

Yet Rhode Island, which suffered record numbers of overdose deaths last year, has already passed a law that will launch a pilot program to operate “harm reduction centers” for two years, beginning next March. Proponents have been encouraged by the fact that the Biden administration has backed “evidence-based harm reduction efforts” as one of its drug policy priorities.

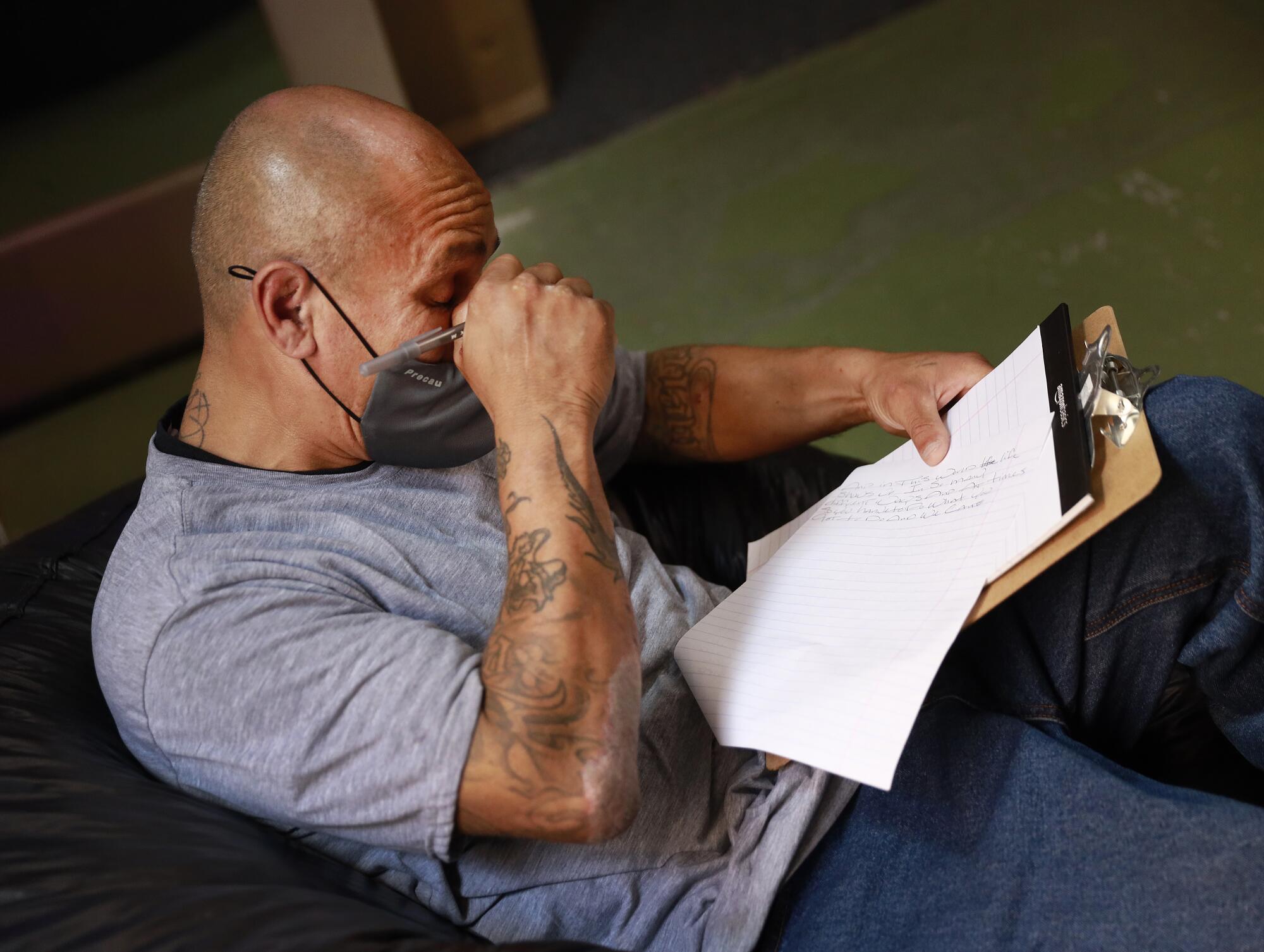

During a poetry class in the back room at the Center for Harm Reduction, Sheridan Bood gently rubbed the shoulder of a woman who had abruptly grown teary after being prompted to write about the word “family.” Others bent over their clipboards, writing intently, as chiming, meditative music played from a smartphone.

One man, asked to write about “fear,” said he worried about picking up a disease and giving it to his loved ones. Another woman had been prompted to write about “friend.” Bood asked what the word meant to her.

“Tremendous grief,” the woman replied immediately.

Bood said she had lost four of her clients to overdoses in the past year. Six times she had personally reversed an overdose with Narcan. She tells clients that if they have to shoot up, “do it across the street so I can see you.”

“So I know you’re OK,” she said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.