Behind the story: Dialogues between prisoners and those they have harmed

After several hours on the phone with Trino Jimenez and Melvin Carroll, I decided to end the interview with what felt like an innocuous question: Could we photograph them for the story?

It had been our second time talking about their unlikely friendship. In February 1986, Carroll had violently murdered Jimenez’s oldest brother, Julio, during a car theft in South Los Angeles.

My story would explore how nearly 29 years later, a letter that Jimenez sent Carroll in prison led to a lengthy correspondence and ultimately a meeting that would change both men. Carroll began to feel remorse for his crime. Jimenez became empowered by the effect his forgiveness had on Carroll.

But after I asked about the photo, Carroll angrily hung up the phone.

“Your question tells me you don’t understand anything,” he said before clicking off.

Jimenez and I were left wondering why he had gotten so upset.

I called Carroll two days later to apologize. I said I hadn’t realized that he might be worried about whether additional exposure could jeopardize his safety — a theory that Jimenez had floated.

That’s not it at all, Carroll said.

He explained that a picture had been too much to ask of Jimenez. Although Jimenez had told Carrol that he had forgiven him, the rest of his family had not. Carroll worried about the backlash that Jimenez might face if a photo heightened the story’s profile, especially one that included the two of them together.

His answer blew me away. It showed how serious Carroll was about his own repentance and never wanting to hurt a member of Jimenez’s family again.

“His friendship means the world to me,” Carroll had said on the previous call. “That’s the only reason you got this interview. I tell you, I owe that man everything.”

::

Although the men’s friendship seems incredibly rare, they are not alone.

I first learned about the California prison program to bring together inmates and the people they have hurt through Sister Greta Ronningen, a chaplain who then was running a prison ministry of the Episcopal diocese of Los Angeles. When I called her up for story ideas, she told me she’s spoken to many prisoners who wish they could reach out to the family they had harmed and are dedicated to trying to better themselves.

“Some families don’t ever want to be approached by the person who caused harm,” she said. “It’s handled very carefully, but when it happens, it’s magnificent.”

I spoke to several people who facilitate the victim-offender dialogues, as they are often known in prisons across the country. Martina Lutz Schneider, a facilitator at the Ahimsa Collective in Northern California, connected me with Jimenez and Carroll.

She also put me in touch with Alan Mabrey and Elle Dowdy.

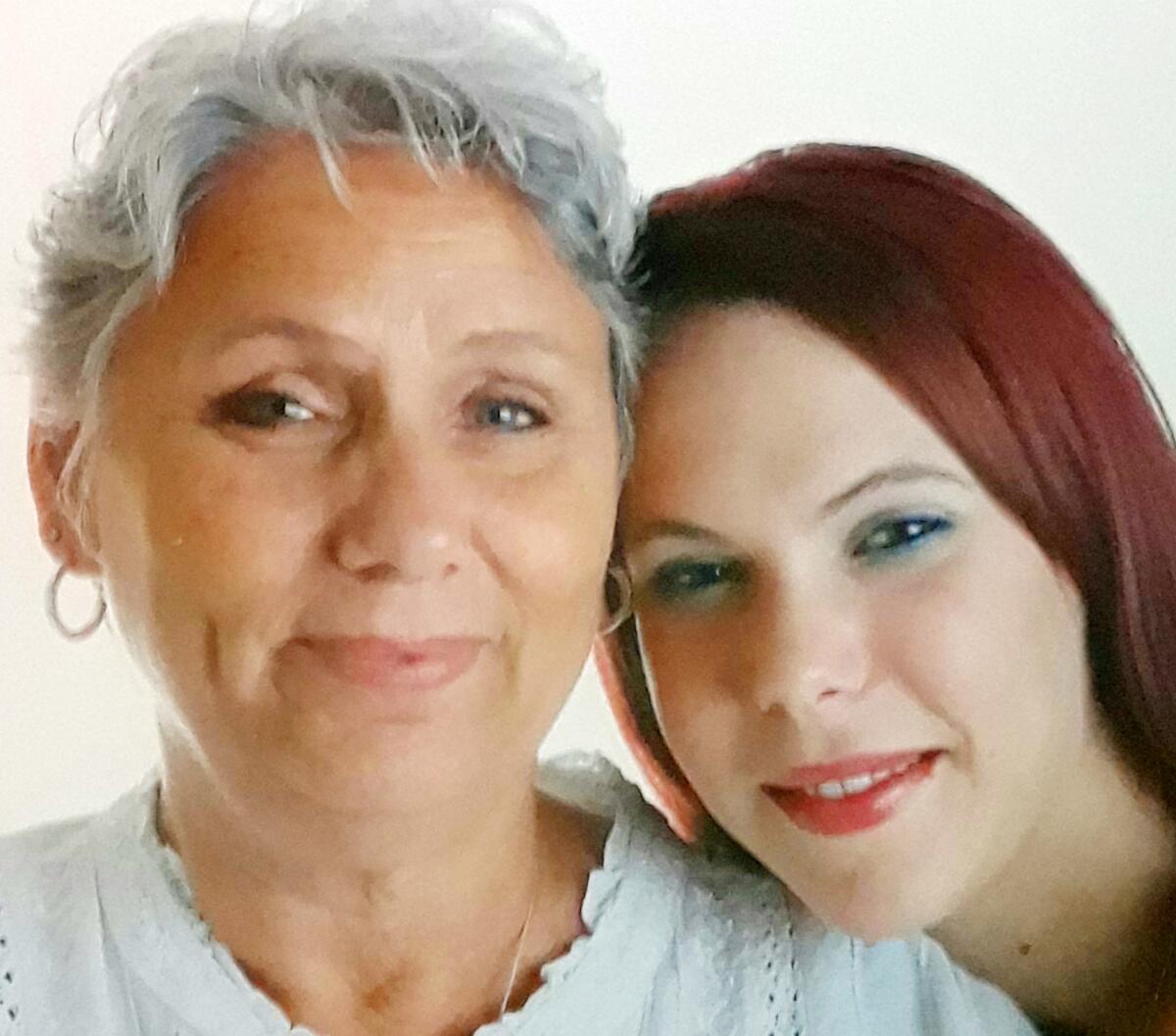

On Feb. 7, 2009, Dowdy’s 24-year-old daughter, Emily, had been walking home in San Diego’s Pacific Beach when she was fatally struck by a drunk driver. Mabrey was sentenced to 20 years to life after being convicted of murder, gross vehicular manslaughter while intoxicated, and a hit and run resulting in death. He already had several prior convictions for driving under the influence.

Dowdy was relieved by the sentence, but she fell into a deep depression. Emily, she said, worked at a Starbucks when she died but had also been a poet and would sometimes call her mom to share her latest poem.

“I just really loved her a lot, and losing her was the worst thing that’s ever happened to me,” she said. “Not just losing her physical presence, but losing our future together.”

Dowdy would only refer to Mabrey as “the man who killed Emily.” But from the beginning, she had an urge to talk to him. Her own family had struggled with alcoholism too.

About nine years after the accident, Dowdy temporarily moved to California to live with family and reached out to the D.A.’s office that had handled the case. She was ultimately put in touch with the Ahimsa Collective, which worked to facilitate a dialogue with Mabrey.

“He’s the person who has done the most harm to me in my entire life, and I don’t know anything about him,” she recalled thinking. “I wanted to understand a little bit about his past.”

The two began exchanging letters and developing a relationship. Dowdy said she was struck by how much courage it would take for him to meet her. She also began using his name.

::

In prison, Mabrey had a hard time coping with his crime.

He would have nightmares about Emily and trouble sleeping. At first, he couldn’t talk about what had happened without breaking up, so he tried to keep busy and not think about it.

“I wasn’t dealing with it real well,” he said. “It was my fault and I couldn’t let the fact go that I took the little girl off this Earth.”

Mabrey began attending Alcoholics Anonymous, which helped him learn how to express his emotions. His eventually decided he wanted to become a substance abuse counselor.

When Mabrey heard that Dowdy wanted to meet, he couldn’t understand it. He had previously sent remorse letters to her but received no response.

“It took a while for me to figure out that actually she wanted to come in peace,” he said. “I was happy being the bad guy in this whole thing, I wasn’t ready for forgiveness.”

::

The pair met on Jan. 15, 2019 in a cold visiting area of San Quentin prison. Mabrey was late, making Dowdy so nervous that she couldn’t think about anything.

But the first thing she did was ask Mabrey if he wanted a hug. Mabrey said “yes, ma’am” and then cried on her shoulder.

Dowdy showed him pictures of Emily, including of her intubated at the hospital. Mabrey told her about the abuse he had suffered as a child.

He said that his father molested him at age 4 and then made him have sex with his sister. At age 6, his father died by suicide. His mother’s new husband would later rape his sister and beat him, Mabrey said.

To cope with what had happened, he began doing drugs at an early age and later turned to alcohol. He would drink until he passed out.

“You can understand why he’d have a problem drinking to keep those thoughts away,” Dowdy said in an interview.

After the meeting, Mabrey said he had felt like he had “lost the bricks on my shoulders.”

“Her part was forgiving me,” he said. “My part was trying to forgive myself. Forgiveness was in that room, and it changed my life.”

Dowdy periodically goes to prisons to share their story, hoping that it helps other prisoners understand the impact of their crimes while recognizing their own humanity. She considers Mabrey a friend and has written to two California governors to advocate for his early release.

“No one said I had to forgive Alan,” she said. “Instead of being stuck as a victim and stuck as an offender, you can come together and heal.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.