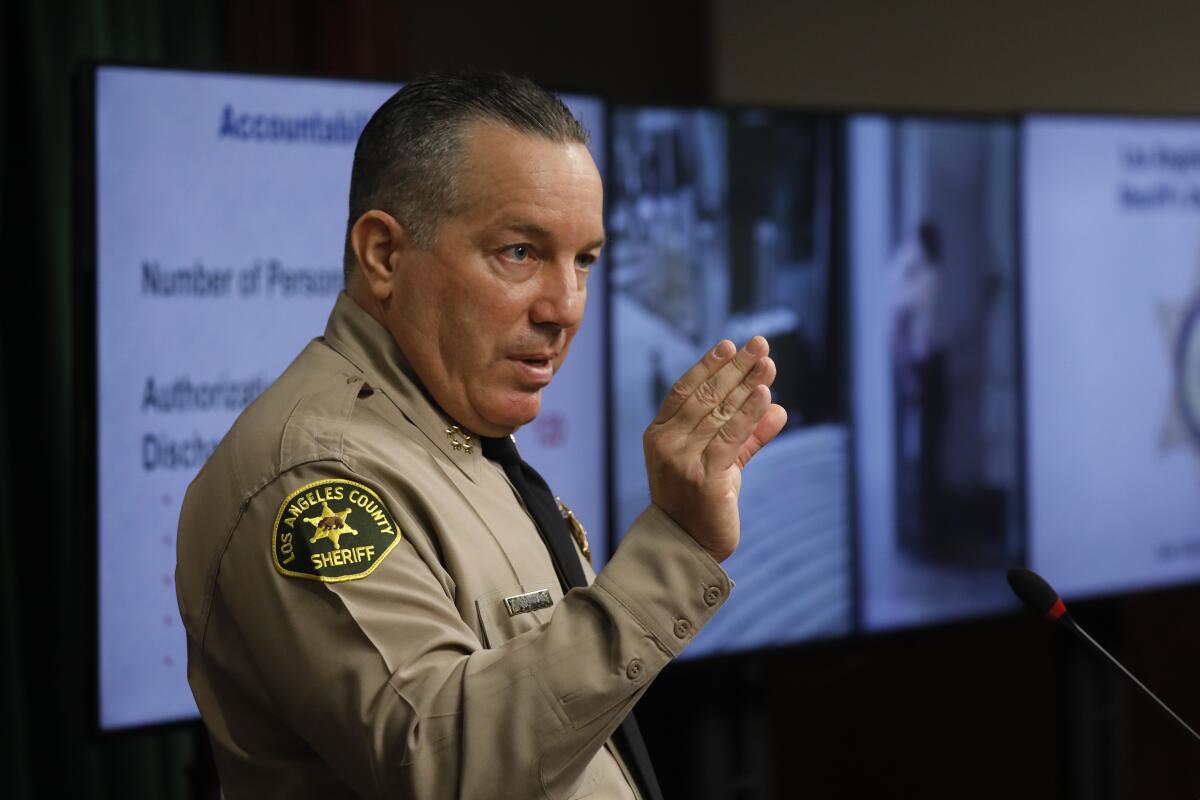

L.A. County sheriff’s unit accused of targeting political enemies, vocal critics

On paper, the deputies are scattered around the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department in various assignments. One is supposed to be working patrol in Lancaster, another in West Hollywood. A third is assigned to a gang crime unit.

In reality, though, the group of nine men and women make up a little-known team of investigators formed by Sheriff Alex Villanueva and other top sheriff’s officials.

Much of what they do, by design, is a mystery to the public and even to most within the department. But as some of the investigations handled by the team have come to light, a common thread has emerged: Their targets are outspoken critics of Villanueva or the department.

The unit, named the Civil Rights and Public Integrity Detail, has pursued a long-running investigation into one of Villanueva’s most vocal critics, L.A. County Inspector General Max Huntsman, and others despite sheriff’s officials being told by the FBI and state law enforcement officials that it appeared no crimes had been committed, a senior sheriff’s official said.

The team also has an open criminal inquiry into a nonprofit that is run by a member of a county board that oversees the sheriff and is associated with county Supervisor Sheila Kuehl, both of whom have clashed fiercely with Villanueva and called for his resignation.

Concern over the team has caused consternation both inside and outside the department. Even the union representing rank-and-file deputies put out a warning that a member of the detail was using “unconventional tactics” to question deputies.

A watchdog panel that oversees the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department voted Thursday to ask county attorneys to determine whether Sheriff Alex Villanueva or his agency broke the law in their handling of a special unit that has been accused of targeting some of his most outspoken critics.

George Gascón, the county’s district attorney, decided he wanted nothing to do with the unit after sheriff’s officials proposed the two agencies create a task force to collaborate on public corruption investigations.

“He’s only targeting political enemies,” Gascón told The Times about Villanueva. “It was obvious that was not the kind of work I wanted to engage in, so we declined.”

Shortly after Gascón refused to partner with the Sheriff’s Department, Villanueva came out as a strong supporter of a recall campaign to kick the district attorney out of office.

The unit has spurred a bitter confrontation between Villanueva and the Civilian Oversight Commission, which oversees the sheriff and his agency. Commission members say they fear the sheriff is using it to intimidate people who challenge him and to score points in personal vendettas, not conduct legitimate inquiries into possible crimes.

The Sheriff’s Department says allegations against the watchdog include conspiracy and theft. “Smells a little bogus,” says Supervisor Sheila Kuehl.

The slow pace of the unit’s investigations and its apparent lack of results have only deepened suspicions.

“These highly publicized criminal investigations have never resulted in charges being filed, suggesting an ulterior motive,” Sean Kennedy, a Loyola Law School professor who sits on the commission, said in a 10-page memo calling for an investigation into whether Villanueva is abusing his power.

The commission subpoenaed Villanueva to appear before them Thursday to answer questions about the team. The sheriff has indicated that he will not show up, saying he is too busy.

In a July letter to the commission’s executive director, Undersheriff Tim Murakami said Kennedy’s memo was filled with “wild accusations” and accused the commission of collaborating with the inspector general‘s office and media organizations, including The Times, to spread false information about Villanueva and the Sheriff’s Department.

Murakami answered initial questions about the unit during a brief interview with The Times in April, but has not responded to repeated follow up questions.

A spokesman for the department told The Times earlier this month that Murakami and other sheriff’s officials would not discuss the detail with the Times reporter who was investigating it because the spokesman claimed the reporter had a conflict of interest. The spokesman repeatedly refused to provide any details of the alleged conflict to a Times editor. The department suggested it would answer questions from “any other” Times reporter. The Times declined to assign a new reporter to the story.

On Wednesday evening, the sheriff released a public statement defending the unit as a tool for fighting corruption and denying it was being used to go after his political opponents.

“The sole responsibility of the Sheriff’s Department is to investigate allegations of criminal conduct as they are discovered, regardless of how inconvenient it may be to the subject of the investigation,” the statement said. “The unit is supervised by the Undersheriff, and I have recused myself from all decision making to avoid any potential conflict of interest.”

Within the department, however, multiple sources said they have heard the team referred to as the sheriff’s “secret police.”

The idea for the team was rooted in Villanueva’s upstart campaign for sheriff in 2018. While trying to persuade liberal voters he would be a progressive reformer, he also vowed to address what he said was widespread corruption among the department’s senior ranks that led to deputies being unfairly disciplined.

After convincing liberal voters he would represent their interests, Los Angeles County Sheriff Alex Villanueva has shifted decisively to the right as a reelection bid looms.

After taking office, Villanueva took steps to make good on his campaign promise, including hiring back deputies who he said had been wrongly fired. He also formed a team to investigate current and former high-ranking Sheriff’s officials over allegations of criminal wrongdoing in cases against deputies, said multiple law enforcement sources who requested their names not be used. There is no indication any of those cases resulted in charges.

A central member of the team, several law enforcement sources said, was Mark Lillienfeld, a longtime homicide investigator who had retired in 2016.

Aides had cautioned Villanueva during his first week in office against bringing Lillienfeld onboard, said Joseph Dempsey, a now-retired sheriff’s chief who attended a meeting with other aides to brief Villanueva about Lillienfeld.

The aides told Villanueva that a few months earlier Lillienfeld, who at the time was investigating a murder for the district attorney’s office, had dressed in a sheriff’s uniform to pose as a deputy to sneak a McDonald’s Egg McMuffin and a cup of coffee in to an inmate at Men’s Central Jail — a violation of jail rules.

Retired L.A. County sheriff’s homicide Det. Mark Lillienfeld enters Men’s Central Jail in a deputy’s uniform and leaves a plastic bag and cup in the inmate chapel.

Sheriff’s officials banned him from county jails and posted notices with Lillienfeld’s photo at jail entrances, directing employees to alert a supervisor if he showed up.

After he allegedly brought contraband into the Men’s Central Jail, officials posted Mark Lillienfeld’s photograph and directed employees to alert a supervisor if he showed up.

Dempsey said Villanueva shrugged off the warnings and downplayed the jail incident, telling the group that Lillienfeld was “way too important” to his future plans. Villanueva, he said, didn’t elaborate. Bob Olmsted, an assistant sheriff at the time who was also in the meeting, corroborated Dempsey’s account.

Dempsey’s account contradicts what Murakami, Villanueva’s undersheriff, said in an interview two years ago, which was that Villanueva was not aware of the Egg McMuffin incident until The Times began asking questions about it a year after it occurred.

In a brief interview after he was rehired in 2019, Lillienfeld said he was reporting to Murakami and assigned to investigate public corruption. Murakami identified Lillienfeld as a member of the unit to The Times.

In August 2019, Murakami made the unusual move of announcing that the department was investigating Huntsman, its top watchdog. In a letter to the Board of Supervisors and a statement at the time, he said Huntsman, members of his staff and sheriff’s officials were under investigation for allegedly stealing confidential files the department keeps on high-ranking officials. He urged the board to sideline Huntsman until the investigation was complete.

The announcement came after Villanueva told Huntsman that if the inspector general went ahead with plans to release a report about the sheriff’s rehiring of a deputy who had been fired over domestic violence and stalking allegations, “there would be consequences,” Huntsman has said.

Caren Carl Mandoyan played a special role last month at the swearing-in of Los Angeles County Sheriff Alex Villanueva, standing on stage and holding the box of gold pins that would adorn the collars of the top cop and his senior executives.

Cmdr. Eli Vera, who is running against Villanueva for sheriff in next year’s election, said he and others advised the sheriff at the time against pursuing the investigation.

“The investigation will be discredited when it’s perceived that you have a personal interest,” Vera said. “It casts a shadow on the legitimacy of the investigation.”

Villanueva agreed to bring the case to the FBI and the state attorney general’s office, said Vera, who was present in April 2019 when the two agencies were briefed. But when the federal and state officials concluded no crimes had been committed and told sheriff’s officials they wouldn’t take the case, Villanueva decided to press ahead with an investigation, Vera said.

Villanueva, Vera said, “hand selected” the team that would investigate the allegedly stolen files and conduct other probes. He added that while the sheriff recused himself from that investigation and others, he often “let it be known what outcome he was looking for.”

L.A. County Sheriff Alex Villanueva has broad legal authority to crack down on entrenched, gang-like groups of deputies, according to attorneys for the county.

More than two years into the investigation, no charges have been filed. In April, Murakami said the case remained open.

“There’s been progress on it,” Murakami said. “Just gathering more information. ... When they move forward with anything, we want to make sure our facts are right.”

When asked in April for an account of the team’s work, Murakami said his investigators were taking cases brought by outside municipalities and the district attorney’s office, and also made reference to the unit having cleared one sheriff’s official of wrongdoing, but declined to provide specifics.

The unit’s investigation into Peace Over Violence, a nonprofit that offers crisis intervention and other services to victims of domestic violence, has also unfolded in a controversial fashion.

Los Angeles County Sheriff Alex Villanueva has demoted a top advisor who is challenging him in next year’s election.

Early this year, Sgt. Max Fernandez, a member of the unit, showed up to the organization’s offices and introduced himself as a sex crimes investigator, said the group’s executive director Patti Giggans, who is also a member of the oversight commission and has been critical of Villanueva’s leadership, including his resistance to complying with information requests and his handling of the Kobe Bryant helicopter photo sharing scandal. Fernandez did not respond to a request for comment.

Fernandez was given a tour of the office and left his business card, Giggans said.

A week or so later, Fernandez showed up again, Giggans said. This time, he had a warrant.

Fernandez was looking for records about contracts the group has with public agencies, including one with the Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority to operate a hotline for reporting sexual harassment on public transit, Giggans said. The warrant also demanded records on communications the organization’s staff had with various county officials, including Supervisor Kuehl, a close friend of Giggans who also has been sharply critical of what she’s described as Villanueva’s resistance to accountability and failure to crack down on gang-like groups of deputies with matching tattoos. Giggans and Kuehl have each called on the sheriff to resign.

The Sheriff’s Department served similar warrants on Metro officials and on Metro’s inspector general. At the time, a Metro spokesman told The Times that “given the limited information contained in the warrant, we cannot determine the nature of LASD’s investigation.”

Rep. Maxine Waters asks U.S. Justice Department to investigate allegations a violent gang of deputies runs the L.A. County sheriff’s Compton station.

What evidence Fernandez and the team used to convince a judge to grant the warrants has not been made public.

Peace Over Violence turned over the records, while attorneys for Metro and Metro’s inspector general objected and asked a judge to block the effort.

In motions to quash the warrants and other court documents, lawyers for Metro’s inspector general and the judge who issued the warrants raised questions about the sheriff’s probe.

After Harvinder Anand, a lawyer for Metro’s inspector general, reported that Fernandez had claimed Judge Ronald S. Coen gave the Sheriff’s Department the green light to “forcibly take computers if the search warrant is not complied with,” Coen responded in a sworn statement that he never told Fernandez that.

Anand said in a sworn declaration that Fernandez told him he “does not think Peace Over Violence did anything” illegal and that he “personally does not see it,” referring to allegations of misconduct by the nonprofit.

Anand also said in the declaration that Fernandez had admitted the investigation into Peace Over Violence stemmed largely from information provided by Jennifer Loew, a Metro employee who is embroiled in a retaliation lawsuit against her employer. Loew has alleged the nonprofit was improperly awarded a series of contracts pushed by Kuehl’s office to run the hotline. Kuehl’s office said they were not involved in awarding the contracts.

The Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department must turn over thousands of pages of records related to deputy misconduct and instances in which deadly force was used, a judge ruled Friday.

Jennifer Loew’s husband, Adam, told The Times that he’s an acquaintance of Villanueva. Villanueva has posted photos on social media with Loew’s daughter.

Adam Loew told The Times he has never discussed the Metro investigation with the sheriff. He said, however, that he did email Murakami to complain about what he saw as the slow pace of the investigation into the hotline.

He said Lillienfeld showed up to his home days later. Loew made a recording of the more than hourlong conversation, which The Times listened to. Lillienfeld told Loew he was “poking the wrong f—ing bear.”

“That’s what I’m telling you, dumb f—, is that clear?” Lillienfeld said. “I can’t make it any clearer than that.”

Lillienfeld did not respond to a request for comment.

During the recorded conversation, Lillienfeld also said that he does not talk with Villanueva about the investigation, even though the sheriff asks for updates. And he suggested to Loew that he believes it would be inappropriate for a sheriff to use a criminal inquiry for political benefit.

Giggans defended her organization’s work and told The Times she believes the sheriff seized the opportunity to harass her and Kuehl by latching onto a campaign against Peace Over Violence that was instigated by a disgruntled Metro employee.

“It couldn’t be more obvious, the retaliatory behavior,” Giggans said.

Murakami told The Times in April that the claims of retaliation are untrue.

One Sheriff’s Department source said: “If they didn’t investigate it, we would be accused of a cover up.”

The unit has also caused tensions within the department.

In February last year, Lillienfeld and another member of the unit, Steve Nemeth, showed up to the sheriff’s station in Compton to interview Deputy Austreberto Gonzalez, according to the deputy’s attorney.

Gonzalez had anonymously reported to the department’s Internal Affairs Bureau that a deputy had been assaulted by an alleged member of the Compton Executioners, a gang-like group of deputies who have been accused of violent behavior and running roughshod over the station.

Word of Gonzalez’s call to Internal Affairs had somehow leaked, and deputies at the station suspected he was ratting out a fellow deputy, his attorney Alan Romero said. Typically, detectives from one of the department’s internal affairs units would have discreetly contacted Gonzalez to gather more information. Instead, Lillienfeld and his partner announced to the employee working at the station’s front desk that they were on a special assignment and asked to speak with Gonzalez, Romero said.

When Gonzalez told the investigators he was worried about them questioning him so publicly, Lillienfeld was dismissive, Romero said. “It’s OK, buddy,” Lillienfeld said, according to Romero. “They’re not going to know.”

Romero said the investigators acted “to retaliate against the whistleblower, to put the whistleblower in danger.”

Lillienfeld and Nemeth did not respond to a request for comment.

Gonzalez is suing the department for retaliation and has testified about the Executioners in an unrelated excessive force lawsuit. Since then, Villanueva has repeatedly called into question Gonzalez’s credibility, saying the deputy has no evidence to back up his claims.

Romero said another one of his clients was followed by Lillienfeld after suing the county. The allegation echoed one made by Huntsman, who said Lillienfeld intimidated members of his staff. On at least two occasions, Huntsman said, Lillienfeld showed up at commission meetings and appeared to follow around members of Huntsman’s team, including one staffer who Lillienfeld trailed into a parking lot.

Around the time Lillienfeld and Nemeth showed up at the Compton station, the Assn. of Los Angeles Deputy Sheriffs sent an email warning its membership about Lillienfeld.

“The department is using some unconventional tactics to conduct internal investigations,” the union said, referring to the agency’s use of retirees hired back on a part time basis. “One such person is retired Deputy Mark Lillienfeld.”

Ron Hernandez, the union’s president at the time who has since retired, said he wanted to remind deputies they could insist on having a union representative with them during an interview.

“The fact that he was out there talking to people was concerning to me,” Hernandez said. “I had no idea what he was doing or how he was doing it other than the fact that it might be a little confusing to the deputies because they don’t know his role either.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.