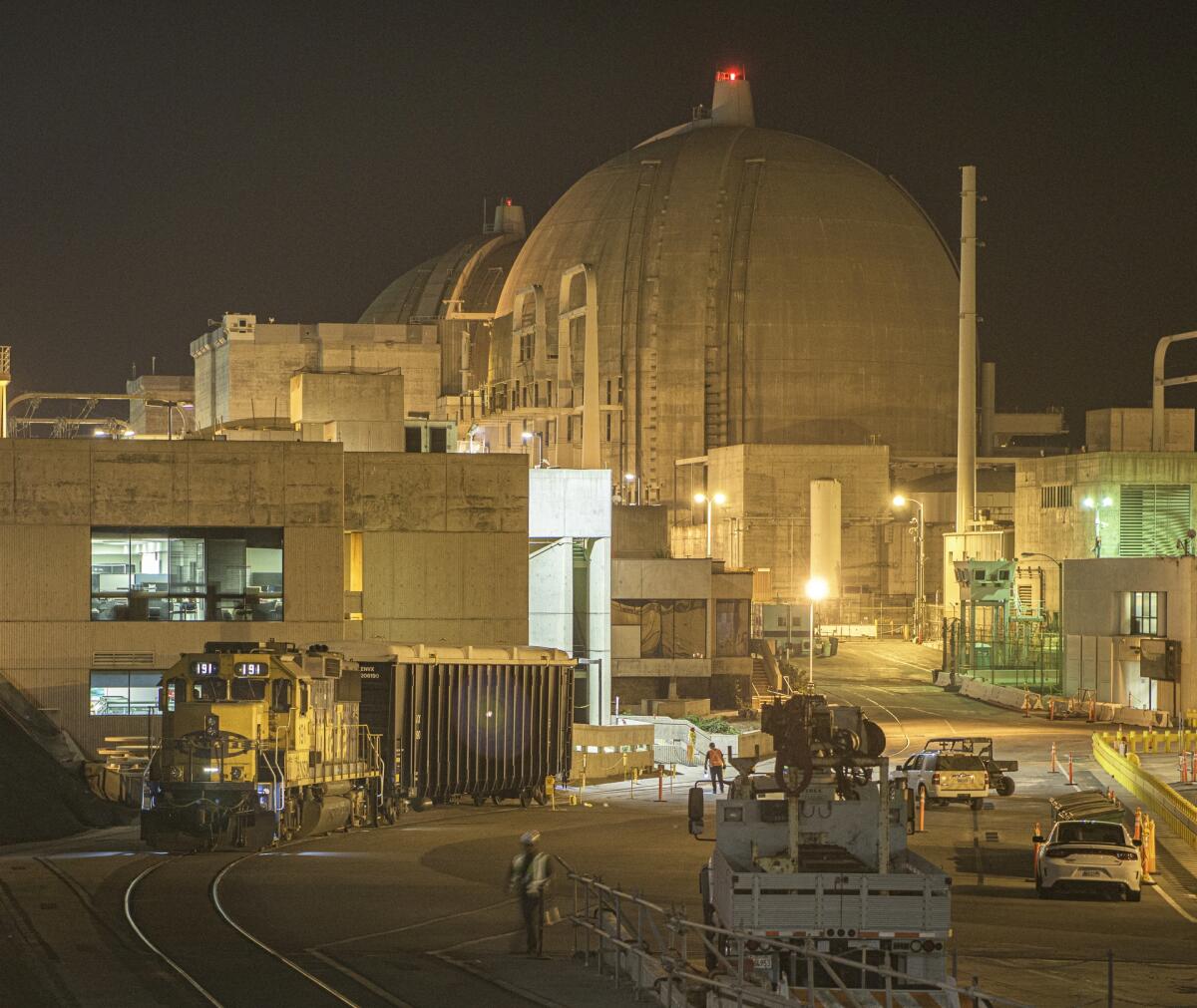

Judge tosses out lawsuit that sought to stop San Onofre nuclear plant dismantlement

Deconstruction work at the closed San Onofre Nuclear Generating Station will continue after a judge in Los Angeles County turned back a lawsuit filed by an advocacy group that wanted to halt it.

In a 19-page decision, Los Angeles County Superior Court Judge Mitchell Beckloff ruled last week that the California Coastal Commission acted properly when it granted a permit in 2019 to Southern California Edison — the operators of the plant — to proceed with dismantlement efforts.

The Samuel Lawrence Foundation filed the suit, arguing the commission violated its own regulations and provisions by issuing the permit.

But the judge, saying the issues before the court were not about the “wisdom of the manner” in which the plant is being decommissioned, ruled that each of the Del Mar-based group’s claims did not show the Coastal Commission acted improperly. The decision gratified the commission, although the larger issue of where to store all the used-up nuclear fuel that accumulated when the plant produced electricity is unresolved.

“While we believe the court’s ruling is consistent with the law, the commission is nevertheless concerned about long-term storage of spent nuclear [waste] on the coast,” Coastal Commission spokeswoman Noaki Schwartz said in an email. “Although we don’t have jurisdiction to regulate this federal issue, we urge the federal government to find a permanent repository.”

Edison officials said they were pleased with the ruling. “We maintain a shared interest with the local communities to move forward with dismantling the plant in a safe and timely manner,” Edison spokesman John Dobken said.

Samuel Lawrence Foundation President Bart Ziegler said in an email that his group “will continue to push for strict monitoring, protocols and handling facilities at Edison’s nuclear waste dump.”

The heart of the lawsuit centered on two spent fuel pools that are scheduled to be torn down.

When the highly radioactive fuel rods used to generate electricity lose their effectiveness, operators place the assemblies in a metal rack that is lowered about 40 feet into a “wet storage” pool, typically for about five years, to cool.

Edison has since taken the assemblies out of the pools, placed them into stainless steel canisters and moved them into two “dry storage” facilities on the north end of the plant. One facility holds 50 canisters and another, more recently constructed site, holds 73 canisters.

Edison says that because the spent fuel has been transferred to dry storage, the pools are unnecessary and should be dismantled.

The Samuel Lawrence Foundation argued Edison should keep the pools in case the canisters are damaged or degrade.

Edison had countered that its current license with the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission prohibits the company from putting the waste back into the pools.

The ruling found that the Coastal Commission made its finding “based upon a fulsome factual analysis” and considered a final environmental impact report certified by the State Lands Commission, along with other environmental documents.

The environmental report also said keeping the pools intact was not feasible because they are connected to other buildings “in the heart of the plant” and would pose “significant challenges” to decontaminating and dismantling the site.

Despite issuing the permit and related measures, the commission has complained about being put in a tough position.

Schwartz said that until the federal government comes up with a long-term storage site, “we are forced to live with the increased risks of storing [waste] on our coast.... We will continue to press the [Nuclear Regulatory Commission] on this issue.”

There are 3.55 million pounds of spent fuel in the canisters at the plant, located between the Pacific and Interstate 5.

San Onofre has not produced electricity since 2012 after a leak in a steam generator tube led to the plant‘s closure.

The plant’s dismantlement began in March 2020 and is expected to take about eight years to complete. Roughly 2 billion pounds of equipment, components, concrete and steel will be removed.

The two distinctive containment domes, each nearly 200 feet high, are scheduled to come down around 2027.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.