How ICE uses Interpol to deport immigrants who could be wrongly accused of crimes

Hugo Gomez spends his days lying on the bottom bunk of a dorm room bed, reading the Bible under fluorescent lighting at an immigrant detention facility a couple of hours northeast of Los Angeles.

He returns again and again to Psalm 40:1: “I waited patiently for the Lord; he turned to me and heard my cry.”

Gomez has been held at the Adelanto ICE Processing Center since August 2019, awaiting deportation. The Guatemalan government alleges he was involved in the 1984 forced disappearance of one revered labor activist and the illegal detention of another when he worked for the Guatemalan National Police, while the Central American nation was enduring a genocidal civil war.

He insists he’s innocent of any wrongdoing and is challenging not only the allegations against him but the controversial federal practice that allowed officials to pursue his deportation based on allegations made by a foreign government.

An evangelical pastor and landscaper from Guatemala, Gomez, 61, has lived in the United States since 1987 and raised three daughters with his wife in their Hawthorne home. His only criminal conviction is a DUI from 1989.

But that other, darker version of Gomez, circulated by the Guatemalan government, could lead to his being sent back to his native country.

In 2009, after the discovery of millions of abandoned police records, Guatemala sent a request to law enforcement worldwide to locate Gomez so he could stand trial. The International Criminal Police Organization, or Interpol, issued a “red notice” with a photo showing a younger, mustached Gomez, his black hair cropped short and a crease between his brows.

Interpol, which primarily serves as an information registry for its 194 member countries, is not a law enforcement agency, and nations are not obligated to act on red notices because they are not arrest warrants.

Gomez isn’t being detained pending a formal extradition. Instead, U.S. immigration authorities want to deport him to Guatemala. He believes that returning there would end in an unfair trial because of the notoriety surrounding his case and, if convicted, possibly his death in prison.

His case hinges on whether Immigration and Customs Enforcement should use red notices as the basis for any deportation, particularly when doing so would preempt constitutional due process rights.

ICE has accused Gomez of lying to cover up his alleged past crimes in order to obtain his green card, which is automatic grounds for deportation. The agency did not respond to numerous requests for comment before this story was published online. Afterward, a spokeswoman declined to comment in detail because the case is pending in court.

“The individual stands accused of material misrepresentations in his application for immigration benefits,” said spokeswoman Danielle Bennett. “ICE’s Homeland Security Investigations (HSI) investigates allegations of fraud and material misrepresentations thoroughly. When the fraud allegations pertain to potential involvement in human rights violations, the cases are handled by historians, attorneys, analysts and agents from HSI’s Human Rights Violators and War Crimes Center.”

While ICE deports hundreds of thousands of people each year — for overstaying visas, entering the country illegally, being convicted of felonies or certain misdemeanors — Gomez’s case is one of several thousand over the last decade spurred by red notices. Between 2009 and 2016, ICE deported nearly 1,800 people who were sought for alleged crimes in their home countries.

Some legal experts on both the left and right say the practice is a form of government overreach and a means to go after immigrants under a legally flawed pretext.

“The reason why I find this process so objectionable is that it outsources the judgment on who is a criminal to some foreign government,” said Ted Bromund, a senior research fellow at the Heritage Foundation, a conservative think tank in Washington, D.C., who has studied Interpol extensively. “I have no issue with the U.S. deporting genuine criminals. But that does assume that the other nation out there is actually identifying murderers as murderers and not political dissidents as murderers.”

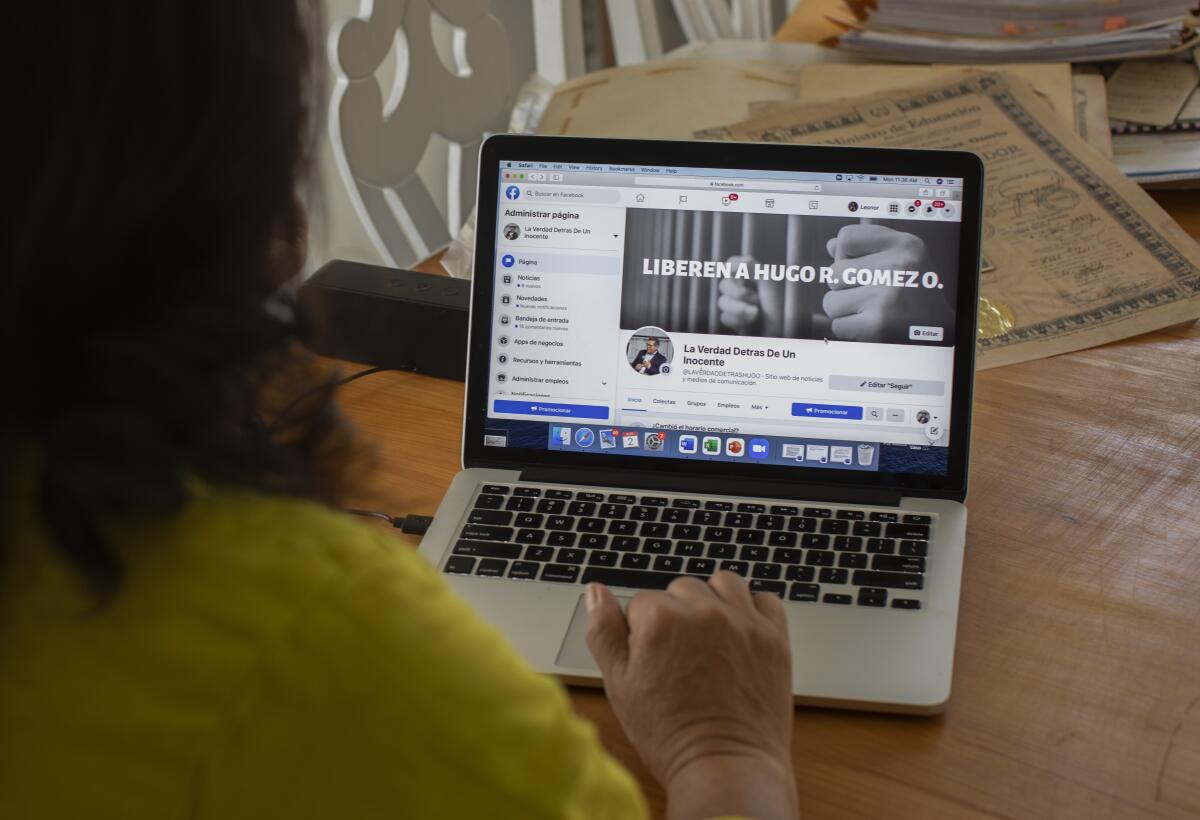

For the last two years, his wife, Leonor, also a pastor, has been engaged in a crusade to set him free.

“The truth must come out,” she says frequently. When he calls, twice a day, their discussions are peppered with “I love yous.”

::

Gomez was born in 1959 in Puerto Barrios, a gulf town near the border with Honduras. He moved to the capital as a high school student and graduated from college as an accountant before becoming a police officer a few years later.

A U.S.-backed coup in 1954 of democratically elected President Jacobo Árbenz ushered in authoritarian military rule and set the stage for the Guatemalan Civil War from 1960 to 1996 between government forces and various left-wing guerrilla groups. It was a brutal conflict marked by human rights violations that killed more than 200,000 people, the majority of them Indigenous Mayan. The country continues to be afflicted by government corruption.

On Feb. 18, 1984, leftist student leader Edgar Fernando Garcia was abducted, tortured and killed, and fellow activist Danilo Chinchilla Fuentes was illegally detained, shot and injured.

Kate Doyle, a senior analyst at the National Security Archive who helped examine millions of Guatemalan National Police records that were discovered in 2005, told the Intercept in 2019 that supporters of the archival project decided not to restrict the documents.

“It was controversial among archivists,” she told the publication. “Though the documents are absolutely chock-full of private information — some of it true, some of it absolutely made up by police — they made the decision that they could not be responsible for censoring information that they felt Guatemalans had the right to know.”

Those archives contain documents that name Gomez in connection with the operation that targeted the activists. In one document, from Feb. 17, 1984, the chief of the Joint Operations Center of the National Police directed members of the Fourth Corps — the unit to which Gomez was assigned — to carry out a “cleansing” operation.

Another document from two months after the operation states that Gomez and three of his colleagues were nominated for an award for their “heroic action” after being attacked by two rebels, from whom they confiscated propaganda and firearms. Two of those men have since been convicted for Garcia’s disappearance and were sentenced to 40 years in prison.

“Even if high level officials in Guatemala benefit from impunity ... this does not mean that low or mid-level officials are not criminally liable for their actions,” ICE attorney Ingrid Abrash wrote in closing arguments for the case in January.

In its judgment against the two convicted officers, the sentencing court in Guatemala said Gomez was “in the company” of other officers when Garcia, the student activist, was detained. The same sentencing document states that the operation belonged to an elite group within Gomez’s unit and that “the structures were designed in a way so that not all the police knew what was going on.”

Gomez said he worked for the national police from 1981 to 1986, rising from secretary to inspector to “third officer.” He said he never arrested anyone without an order from a judge and never discharged a firearm while on duty. He spent his days typing up police reports or occasionally assisting other officers with neighborhood watch, he said.

He was fired for abandoning his post to go drinking. He says he simply misunderstood the protocol and failed to check in at the police station to be relieved of duty.

Gomez said he became more of a target for guerrilla violence as a former police officer than he’d been as an officer with institutional protection. From inside their home, the couple and their young children would hear screams at night and wake up to see who had been murdered.

The family fled to the U.S. in 1987. Years later, they received green cards through the Nicaraguan Adjustment and Central American Relief Act.

Gomez’s lawyers, whose law practice focuses on victims of persecution, say they searched for a reason not to take his case but couldn’t find any “smoking gun.”

“This is not a case about innocence, this is a case about due process,” attorney Monia Ghacha said.

Bromund, of the Heritage Foundation, analyzed Gomez’s case for the family and concluded that the red notice fails to meet Interpol’s administrative requirements because it did not describe the role of the person named in the offense.

In February, an immigration judge ordered Gomez to be deported, finding that there was enough evidence to believe he had participated in the operation. Gomez’s lawyers appealed and the case remains pending.

::

Using red notices for predominantly political, military, racial or religious reasons is against Interpol’s constitution. But some countries, including Russia, Venezuela and China, are known for deploying red notices against political opponents who flee persecution, said Sandra Grossman, an immigration attorney who specializes in Interpol abuse cases.

Through civil immigration proceedings, foreign governments achieve what wouldn’t be possible under the scrutiny of formal extradition proceedings in federal court.

“ICE does their bidding for them by putting these individuals into deportation proceedings,” she said.

Guatemala’s track record in the Interpol system is not substantial enough to conclude that its requests should be presumed to be abusive, Bromund said. But at least one high-profile Interpol abuse case has involved Guatemala.

Post-war anti-corruption mechanisms have crumbled in recent years. Guatemala was the only country in the world with a United Nations commission charged with addressing government corruption, until former President Jimmy Morales forced its closure in 2019 while he himself was being investigated.

Guatemala’s Special Prosecutor Against Impunity (FECI), one of the few remaining institutions to fight corruption, is the target of frequent attacks. In April, Congress refused to swear in Magistrate Gloria Porras — a stark adversary of impunity — after she was re-elected to the Constitutional Court, even as three other magistrates who raised corruption red flags were approved.

“It is generally the case that the nations which struggle, or fail, to maintain the rule of law domestically are also the nations that abuse Interpol’s rules,” he said.

Under federal law, red notices alone don’t provide enough evidence of criminality to arrest someone. A foreign government can issue a diplomatic request for a suspect’s provisional arrest, but the U.S. attorney’s office ultimately decides whether to issue a warrant for extradition.

Rachael Billington, a spokeswoman for Interpol, said a notice is published only if it complies with Interpol’s constitution. A task force conducts legal compliance reviews for all red notice requests, she said, and is in the process of reviewing tens of thousands authorized before 2016.

Billington did not directly respond to a question about misuse of red notices, except to say that Interpol consistently reviews procedures to ensure “the greatest possible level of integrity in the system.”

“Whenever new and relevant information is brought to the attention of the general secretariat after a red notice has been published, the task force reexamines the case,” she said.

From detention, Gomez has written journal entries on lined paper detailing his experience. Last year, he contracted the coronavirus, which has prevented his wife and daughters from visiting him since February 2020.

“My fear is strong,” he wrote in April, “because 20 months locked in this detention center not only have provoked issues of physical, emotional and psychological health, but also the loneliness and abuse have driven me to suicidal thoughts.”

In a phone interview from the Adelanto facility, Gomez said that his troubles began in April 2009, after the legal permanent resident initiated his naturalization for U.S. citizenship.

A few weeks later, family members in Guatemala called to say that news reports had begun to circulate that he was wanted for extradition and arrest. He believes he was wrongly targeted after being confused for another officer in a politically motivated scheme for restitution money from the Guatemalan government over the crimes.

On a Monday morning a decade later, Gomez had just left for work when six ICE vehicles pulled him over two blocks from home.

Around 2015, ICE started a program increasing its collaboration with Interpol to systematically target people with red notices. Bromund said he suspects the Obama administration’s desire to appear tough against foreign criminals encouraged officials to rely more heavily on the notices. That desire extended through the Trump administration.

The circulation of red notices has multiplied over the years. In 1998, Interpol published 737 red notices, Bromund said. In 2019, the organization published more than 13,000.

Red notices can be challenged directly through the independent Commission for the Control of Interpol’s Files. But that process can take several months, and time is not on the side of immigrants fighting deportation.

In May, U.S. Sens. Roger Wicker (R-Miss.) and Ben Cardin (D-Md.) reintroduced a 2019 bill to fight alleged Interpol abuse that had been derailed by the pandemic. The Transnational Repression Accountability and Prevention Act would prevent any U.S. agency from arresting someone based solely on an Interpol notice without an accompanying arrest warrant. It would also prevent federal agencies from using Interpol notices as the sole basis for detaining, deporting or denying citizenship or other immigration benefits without independent credible evidence.

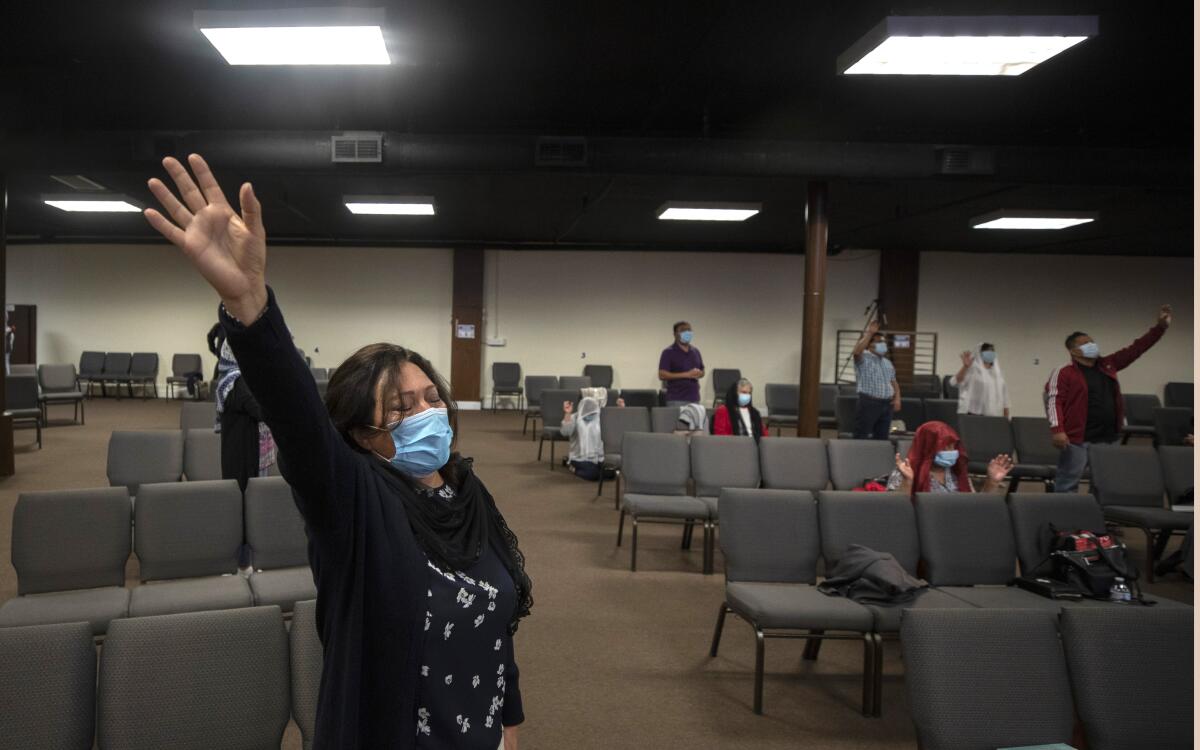

In early May, Leonor gathered with a dozen congregants at the Gardena church that she and her husband started in 2019, Iglesia de Cristo Lluvias de Paz. The majority of the 60 congregants are fellow Guatemalan immigrants.

One by one, congregants took the microphone to plead for their pastor’s return.

“Open the doors of Adelanto,” one said. “You are the God of the impossible. The life of our pastor is in your hands.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.