Inside the white van parked in the concrete bed of La Canada Verde Creek, Wendy Ruvalcaba rooted in her bag for her phone as it chimed.

“Tell me you found her,” the nurse said in answering the call.

Ruvalcaba and the rest of the street medicine team had spent hours trundling down the creek that Wednesday in their Los Angeles County Department of Health Services van.

They had gotten five people vaccinated against COVID-19 that day, climbing the steep slopes of the channel in this industrial stretch of Santa Fe Springs to offer the shots to people living in tents and under tarps.

They had stopped to offer medical care for swollen or twisted limbs, distributed meals wrapped in plastic, and handed out medicine that could reverse a deadly overdose.

But the nurse had been holding out hope, as the hours passed, that they would find her: the woman who had been booted from one encampment after another because of her screaming. The woman whose belly was steadily swelling.

“This is like the 10th time I’ve stopped to try to find her,” Ruvalcaba said a few minutes before getting the call and hustling up the embankments to a makeshift shelter tucked away under a rumbling overpass.

Street medicine has been around in Los Angeles for years as health providers have tried to reach the surging numbers of people on the streets — more than 66,000 countywide in the last count. The Street Medicine Institute has tallied more than two dozen such programs across California.

For the L.A. County Department of Health Services, COVID-19 marked the beginning of its own street medicine teams venturing into encampments. Their hope is that it won’t be the end. As of late August, health officials said roughly 25,000 homeless people across the county — about 38% — were fully vaccinated, a rate lagging behind the county average.

But the virus is just one in a battery of health threats to homeless people, who are nearly three times more likely to die than people of the same age and gender in the general population, according to an L.A. County Department of Public Health analysis. Another study that spanned a decade in Massachusetts found that people living on the streets had mortality rates nearly 10 times higher than the broader population.

Drug overdoses and heart disease have been the biggest causes of death for homeless people in L.A. County in recent years. Doctors say even seemingly small wounds from cooking or fixing a bike can become grievous on the streets without medical care.

As it stands, this L.A. County program, known as the Housing for Health Unsheltered COVID Response Teams, is funded through the end of this year, using money tied to COVID-19 relief. More than a dozen teams have been sent out across the county under the program. But it is unclear what will happen in 2022.

At least eight people died while they were living at the Airtel Plaza Hotel in Van Nuys, where hundreds of homeless people have been housed through Project Roomkey.

Street medicine providers have welcomed new funding, but with money tied specifically to COVID-19, “there is a risk that when that money goes away, we won’t be able to sustain what we’ve already started,” said Street Medicine Institute vice chair Brett Feldman, who is not affiliated with the Department of Health Services street medicine team.

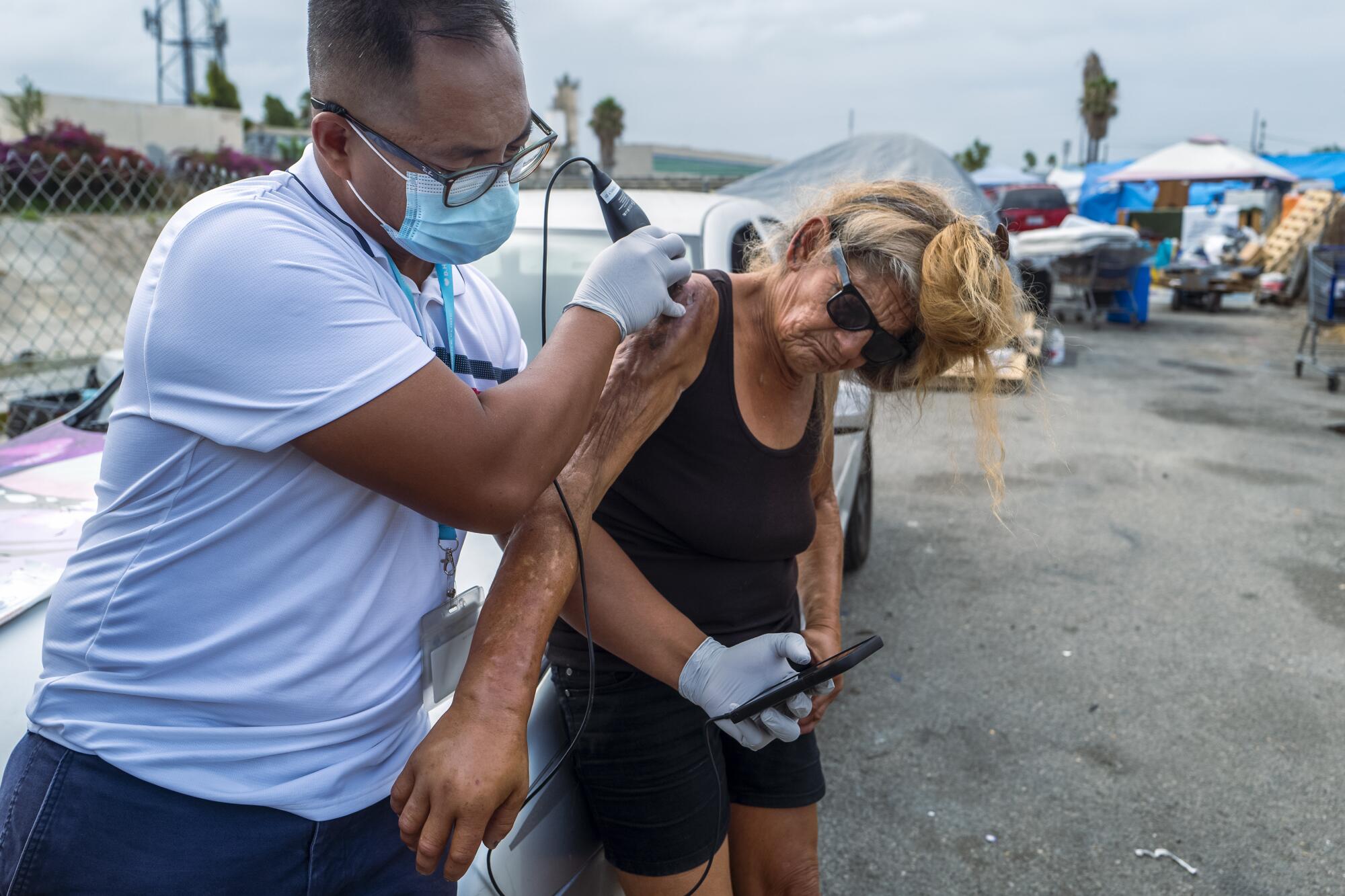

When the L.A. County team made its first stop at an encampment along the riverbed that Wednesday, it quickly found a taker for the COVID-19 vaccine. But Dr. Absalon Galat spent much of his time examining Luz Juarez, whose arm was puffy from an abscess that had stubbornly resisted the antibiotics they had previously provided.

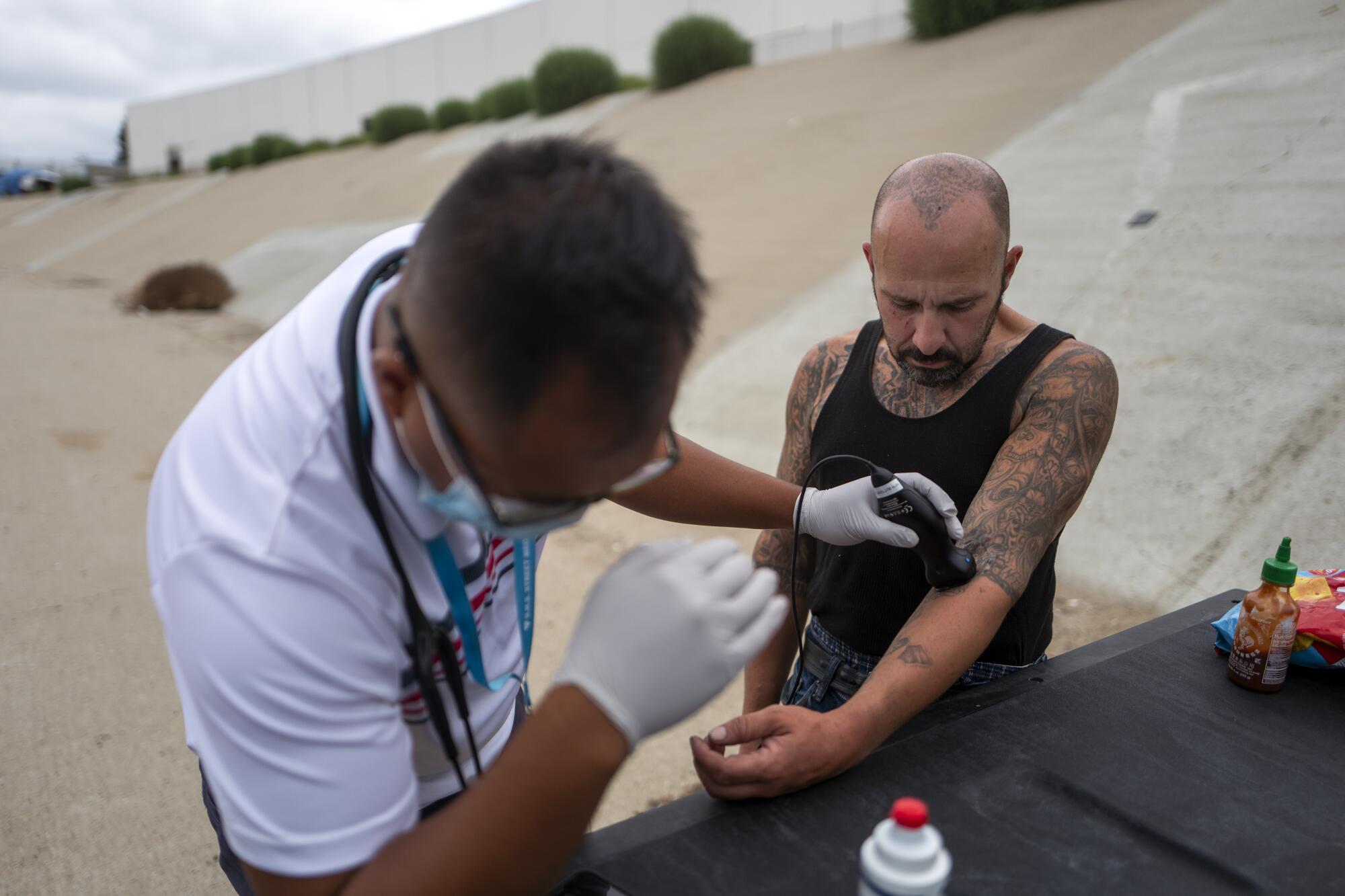

Ruvalcaba fitted Juarez’s swollen arm into a sling. “You had breakfast yet, Luz?” the nurse asked as she stabilized her hand for emergency medical technician Timothy Samuelson, who was pricking her fingertip to check her blood sugar. Juarez said no.

Before leaving, the team set packaged lunches on the wooden platform of her tent overlooking the creek. Galat said they would return the next day to safely open and drain the abscess.

“Anytime somebody leaves their spot, they open themselves up to robbery.”

— Lisa Massey, who has lived along the creek for three years

Her vital signs had reassured him she wasn’t suffering from septicemia — a bacterial infection reaching the bloodstream. “I’ve lost a lot of patients like that on the street,” Galat said quietly after stepping away.

Wounds make up a lot of the team’s daily work. Tending to them can be a gateway to a deeper conversation between a health worker and a patient, Galat said in an earlier interview. For people who routinely go ignored in public, the doctor said, the simple act of dressing a scrape or cut “releases a lot of their tension for people who haven’t been touched.”

Even when homeless people are insured, the vast majority don’t regularly see a health provider in a brick-and-mortar clinic, researchers in L.A. County have found. Some struggle to reach a clinic without transportation. Some distrust doctors after demeaning experiences. And some fear leaving their tents.

“Anytime somebody leaves their spot, they open themselves up to robbery,” said Lisa Massey, who has lived along the creek for three years. She also has to worry about her pets — three dogs and two cats — if she abandons her site perched over the concrete riverbed.

So she has relied on the team in the white van to manage her diabetes and rheumatoid arthritis. Last year, she said, she went septic — “my gall bladder had a leak in it, I guess” — and ended up in the hospital for weeks.

It was detected, she said, because the team stopped by and took her temperature. “These guys are lifesavers,” said Massey, 56.

Down the concrete artery the team members drove that Wednesday morning, crossing the foul rivulet that ran down the channel, sidestepping the flotsam of broken bottles, cigarette butts and other litter when they stepped out.

At times they marveled at the handmade homes people had cobbled together, boarding up the undersides of overpasses to make precarious apartments. When one man guided them to a secluded encampment, tucked into the side of a darkened tunnel, vaccine logistics program manager Daniel Newell reacted with quiet awe.

“It’s got a legit door,” he later enthused to a co-worker.

Newell said he had been on this riverbed dozens of times and never encountered it before. “Those are five people that we’ve missed” in the past, Newell mused as he hustled back to grab plastic bags loaded with packaged meals and other supplies for them. “That makes my head spin.”

Sometimes when the team spotted someone pacing down the creek bed or cycling past on a bicycle, Newell would slow down the van and call out to them. One woman took off before the van rolled up, wheeling her bicycle off in the distance.

Ruvalcaba said that when medical students accompany the team, they are cautioned against wearing white coats, because “it doesn’t go over very well.”

Galat said he once had a patient who was spitting up blood, but told him, “I’d rather die than go to the ER, because of the way they’ve treated me in the past.”

At a city-funded homeless shelter in Venice, 37 people have tested positive for COVID-19 — the largest current outbreak in a homeless facility in Los Angeles.

One woman camped along La Canada Verde said she didn’t like going to clinics. “Just the way people look at you,” said the woman, who didn’t want to give her name. “If you’re not, you know … society.”

But she welcomed Ruvalcaba and the rest of the team from the rim of the concrete creek. They fed treats to her dogs, commiserated about a friend killed recently in a hit-and-run and helped her clean a spider bite.

The van slowed to a stop below another tent perched above the creek. Galat, who was following in his truck, got out to examine Roy Ramos, who said a needle had broken off in his arm.

Ramos, 42, said he had been camping along the creek bed for three months. He previously lived with his mother, he said, and ended up in a tent after she died. He leaned against the back of the truck bed as the doctor held an ultrasound wand over his inner elbow, studying the images on his smartphone.

“Is it painful when you bend it?” Galat asked.

“Sometimes,” Ramos said quietly.

Galat estimated the lost needle was about a centimeter deep. It would need the attention of a surgeon, he remarked. Ramos said he had already gone to see a surgeon about it, but “he sucked.”

“He kept pushing it down,” Ramos said later.

The team conferred about how to get his medical records and refer Ramos to another surgeon. “Roy, do you mind if I take a feel?” asked physician assistant Haley Bogdanovich, gently touching the spot before asking him about his migraines.

“Would you describe it like a band is going around your head?” she asked.

“Like a vise,” he said.

California lawmakers have been hoping to foster programs like this with Assembly Bill 369, legislation that would facilitate Medi-Cal reimbursement for treating people on the street. Feldman said it would be a game changer for programs that have relied on a patchwork of funds because Medi-Cal doesn’t “recognize the street as a legitimate place to deliver healthcare.”

State Sen. Sydney Kamlager (D-Los Angeles), the primary author of the bill, said the majority of homeless people are eligible for Medi-Cal but never see a primary care doctor “for very obvious and legitimate reasons — and all of that is costing the system hundreds of millions of dollars” in later visits to emergency rooms.

Although the bill has garnered broad support from homeless advocates and medical groups, it has been opposed by the California Department of Health Care Services, which argued it would duplicate services under a new system for managing care, and by the Department of Finance, which raised concerns about costs.

In the creek, the van stopped again to administer COVID-19 vaccines at another cluster of tents. At another encampment, Bogdanovich prescribed suboxone, a medicine that can decrease the craving for opioids.

And perched near the Del Amo Boulevard underpass they found Barry Gadient, who wanted to know how he could get proof of his COVID-19 vaccination. Newell tried to pull up the record on his phone without success.

“If we can find anything, Wendy will bring it back out to you,” Newell promised.

“I think it would be easier to go to Kinko’s and just make a card,” Gadient joked, then reassured him, “I’m being a smartass.”

Gadient, 60, peppered Newell with questions about COVID-19: If the virus was airborne, why did people make such a big deal over washing your hands? Wouldn’t wearing a mask weaken his immune system? Newell responded to each question, explaining what physicians had learned about the virus.

It was one of the more measured conversations he’s had on COVID-19, Newell said. In Lancaster, he said, someone had accosted him while he was giving vaccinations to homeless people to ask, “How does it feel to assassinate your fellow Americans?” He told the man he was there to help, but “your healthcare is always your choice.”

As they neared the end of their day, Ruvalcaba pointed Newell to a spot where the pregnant woman was rumored to be. When they finally found her, the nurse stepped behind the tarps with Galat to examine her. The doctor ran the ultrasound wand over her belly and the black-and-white image of a face appeared, lunar and magical, on the screen of his phone.

Ruvalcaba, returning to the van, said the woman had asked her to send the image to her grandmother. Galat worried aloud about the dwindling time to try to get her housed before she gave birth. Even getting the woman to a clinic for pregnant women at high risk would be difficult, he said.

Pregnant women are “probably the toughest cases that we have,” Galat said. Many have suffered earlier trauma in hospitals. If they have used drugs, they often are fearful of losing custody of their children.

Because of distrust, he said, it isn’t as simple as “us telling them, ‘You’ve got to go in, you’ve got to go in’” to the clinic, the doctor said. “We try and support them in whatever decision they want.”

Before they left, the team members gave the woman prenatal vitamins and medication to ease her nausea. Galat was planning to reach out to a housing agency for help.

He just hoped they would be able to find her again. The woman might relocate soon, the doctor said, out of fear of getting ejected from that spot.

“There’s the medical complexity,” Galat said, “and then there’s the social reality of the context of our work.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.