Column: The recall circus has managed to ignore staggering crisis ripping apart California

Millions of dollars have been spent.

Punches and counterpunches have been thrown.

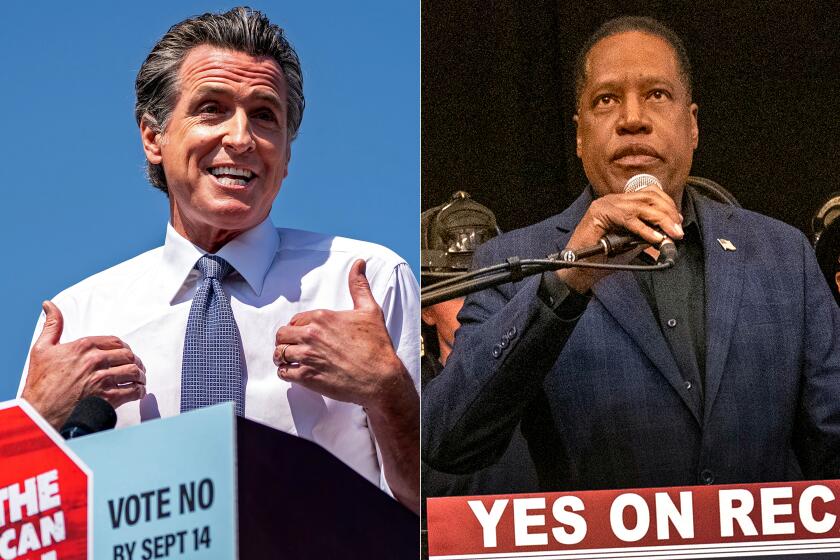

A gubernatorial recall election that is costing taxpayers an estimated $276 million — one year before Gov. Gavin Newsom would have had to run for a second term anyway — is just about behind us, and little has been accomplished.

Political campaigns, especially in this era of toxic division, typically generate lots of heat and very little light. This one has been no different, except for the absurdities of a throw-the-bums-out playbook in which the bluest state could end up being governed by the reddest of challengers, and a mere 15% to 20% of the vote could make that happen.

But if the recall election is about leadership failures and the many problems that have resulted — including homelessness, crime, the state of public schools and the quality of life — a major reason for all these woes has been virtually ignored before and during the campaign.

A staggering level of income inequality has affected nearly every aspect of life from cradle to grave, making California home to both the United States’ largest economy and the nation’s highest rate of poverty when the cost of living is factored in. And the pandemic has widened the divide.

In May, perhaps feeling the heat of the recall effort, and sitting on a multibillion-dollar budget surplus that is a reflection of how the rich get richer even during a pandemic, Newsom proposed $100 billion worth of programs to support businesses, train workers, fix infrastructure and address homelessness. But this redistribution of wealth would be spread out over several years and could fail to significantly reverse trends long in the making.

“Income inequality has risen substantially in the past several decades, with relatively little progress over the long term for the lowest-income families,” said a report last December by Sarah Bohn and a team of researchers at the Public Policy Institute of California. “The effects of the current recession are concentrated among low-income workers, African Americans, Latinos and women.”

“Enough!” Some election chiefs in California are pushing back against election watching groups, which they say are spreading misinformation that could discourage voting.

These changes have been tied to global forces and began so long ago that I saw the beginning of them as a young resident of the Bay Area town of Pittsburg. When I was coming up, nobody gave a second thought to where they’d get a job or whether they could afford to buy a house. Jobs were there for the taking at U.S. Steel, Johns Manville, DuPont, Allied Chemical and Continental Can Co., where I got a job on the assembly line one summer.

You could easily afford a three-bedroom rancher on those jobs; you sent your kids to college, retired with a pension and went on a cruise every year.

Almost all of those jobs are gone now, along with the ladders of upward mobility. Now, if you don’t go to college, and maybe even if you do, you get a job at Sam’s Club, share an apartment and struggle to pay for groceries and car insurance, without enough of a cushion to handle a modest financial emergency.

Six years ago, the Boeing C-17 assembly plant closed in Long Beach, eliminating the last of the state’s large-scale blue-collar aerospace assembly jobs. I shadowed employees who made $40 an hour, with benefits, as they struggled to find jobs that paid even half that. In fact, roughly one-third of California’s workforce has made $15 an hour or less in recent years.

“Instead of $40, they want to bring us to our knees with $10 an hour, and you’ve got a thousand people lined up in the street to get it,” said Randy Sossaman, a union leader who worked on the C-17.

California Gov. Gavin Newsom was a rising star in Democrat politics. How did he come to face a recall?

Yesenia Barrera, 23, fits perfectly into Sossaman’s take on California’s new economy. The Inland Empire resident worked in fast food and sales at or near minimum wage, then felt lucky to land an Amazon warehouse job at $12.75 an hour, which made it possible for her to rent a room in a house she shared with two roommates.

“I had been hearing they were going to increase it to $15 an hour,” Barrera says, so she didn’t complain about the demands of the job. But she was fired because the company’s computer algorithm for monitoring production said she wasn’t keeping up with the desired pace.

“We are carrying, bending, reaching, twisting and packing items from 30 to 60 pounds for hours a day with no proper rest time,” Barrera told an Assembly committee in Sacramento. “The algorithm fired me, and other workers like me, though we were working as hard as we could.”

Barrera told me she hadn’t given much thought at the time to the fact that her boss is one of the richest men in the world, with 950,000 U.S. employees generating $368 billion in revenue last year for Amazon. But now she is an organizer for the Warehouse Worker Resource Center and said it feels good to be part of a cause that’s challenging the status quo. A bill to help workers fight speed quotas cleared the state Senate on Wednesday.

The link between this economy, the housing crisis, homelessness and public education became all the more clear to me three years ago when I spent several weeks at Telfair Elementary in Pacoima. Bashing the state’s schools is a popular sport, especially during the recall campaign, but history offers some needed context.

California schools never fully recovered from the busing and white flight of 50 years ago, nor from the shredding of budgets and local control under Proposition 13. Anyone can point a finger at the failures since then of school administrators, board members and union leaders, as I’ve done now and again. But until recent infusions, California schools were shamefully underfunded.

California will have its second gubernatorial recall in 18 years. Why is this liberal state so recall crazy?

When I visited Telfair, more than 20% of the students were classified as homeless, and virtually every one of them was poor enough to qualify for food assistance. Poverty was the single biggest challenge, and it’s worth noting that Telfair sits in the graveyard of the old economy.

Lockheed Martin, Rocketdyne, General Motors and other major employers have closed their doors. On the very site where Price Pfister once manufactured bathroom and kitchen faucets, a discount store sells the same products, now manufactured in Mexico.

“With a high school diploma, you could work at Lockheed or Price Pfister, somewhere in manufacturing, and you were able to support your family. Those jobs are gone, and there’s nothing out there now for a family to support itself on one job,” says Jose Razo, an L.A. Unified School District administrator who grew up in the neighborhood and was principal of Telfair when I spent time there.

And yet, Razo says, real estate prices have soared in Pacoima, San Fernando and Sylmar, so much so that ordinary working people who are trying to buy houses “are getting outbid. It’s ridiculous.”

Housing is, in fact, at the core of California’s income inequality. In my lifetime, the creation of new housing units has not kept up with population growth, so low supply and high demand means that many working people are priced out of the market and many others are spending ridiculous portions of their income on rent and mortgages.

Income inequality in the post-industrial economy is a nationwide phenomenon, with once-thriving cities and towns pummeled from West Coast to East, and everywhere in between. But California happens to be home to the new economy, to behemoths such as Google and Facebook, among others. They are the new factories, and they manufacture millionaires and billionaires.

There’s enough money floating around in the high-functioning portion of California’s economy to flush the lower echelons of the workforce out of their homes and neighborhoods and further from the modest dream of Golden State, middle-class comfort.

“It drives me crazy that this is not being dealt with,” said Darry Sragow, publisher of the nonpartisan California Target Book, who said the root causes of California’s longtime structural failures have been all but ignored for years. He covered that 10 years ago in an op-ed for the Sacramento Bee in which he wrote:

“Many of the jobs lost in the Great Recession are never coming back. Never. … Americans are overwhelmingly unhappy with the direction of the country. Californians are even more distressed about the direction of our state. No wonder. Lost jobs, lost fringe benefits, lost pensions. … Robbed by Wall Street barons. … But most of all, we are scared, justifiably, by the extent to which the earth is shifting under our feet. Voters sense it, but our governments appear oblivious.”

Over the course of the last month, Gov. Gavin Newsom and his supporters have expanded and reconfigured the likely electorate.

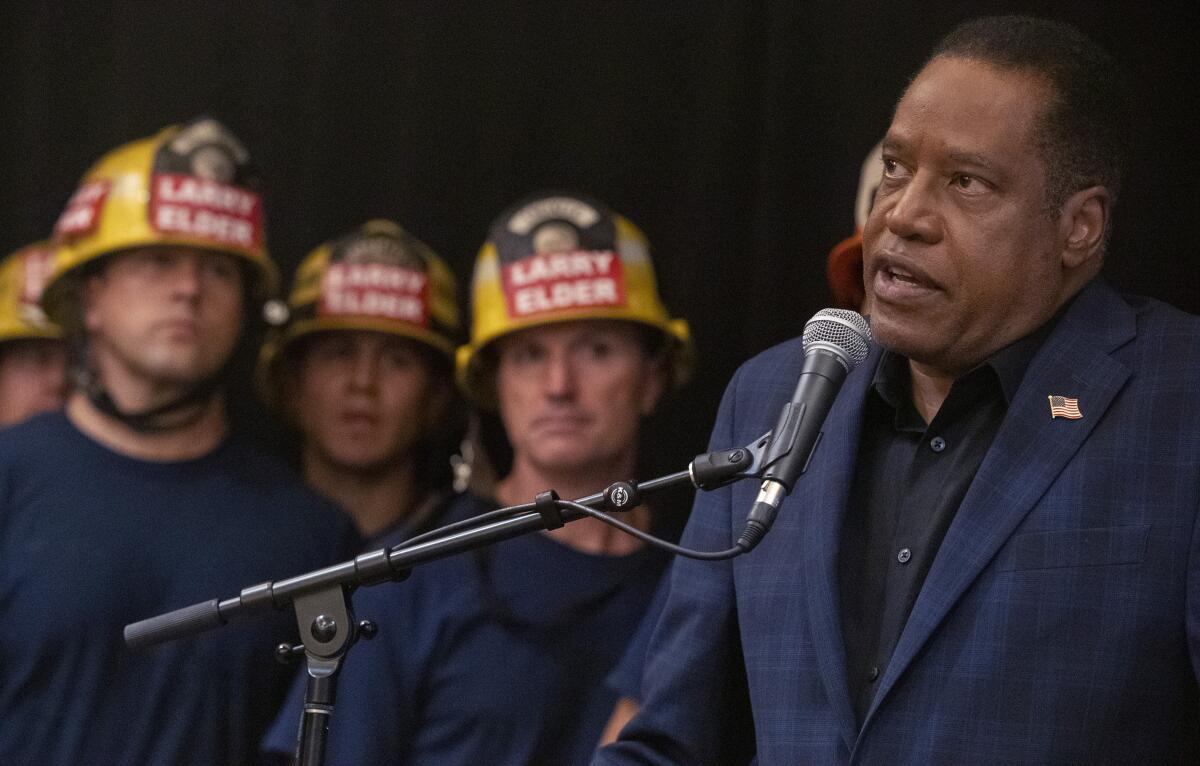

Sragow said Donald Trump either recognized the disparity and simmering resentment or stumbled upon it when he first ran for president. And there are many echoes of that movement in the current California recall campaign, in which radio show host Larry Elder is a proud Trump cheerleader.

The problem, of course, is that Trump didn’t deliver. Manufacturing didn’t return as promised. Coal mines did not fire up again, thankfully. His promises of a national infrastructure program and cheaper, better healthcare for all were colossal flops.

The most enduring Trump legacy is the myth that simple solutions exist for every problem, and when they’re not delivered, it’s somebody else’s fault. Immigrants. Elitists. Lying media. Corrupt Democrats. Crooked election officials. None of which begins to address the ravages of what Trump called a rigged system that worked against the little guy.

And many of the fixes being sold by recall candidates — tax cuts, restoring the death penalty, releasing fewer prisoners, school choice, harsher policies on immigrants, loosening coronavirus protocols, relaxing environmental protections, police enforcement of homeless encampments — are red-meat talking points rather than viable solutions to the state’s most vexing problems.

Not that Democrats have delivered the goods.

“As far as I’m concerned,” Sragow said, “what a strong Democratic governor would do is say, ‘This is what’s going on in the world, and we’re Californians. We’ve always adapted, and we have to take a good hard look at how we’re going to do that and come up with a credible, serious plan to create a new future for California.’”

And what would that future look like?

No easy answers there, but without an infusion of living-wage jobs, more housing — at lower costs — would offer much-needed relief. But despite holding a supermajority in Sacramento, Democrats have repeatedly swung and missed in attempts to deliver game-changing legislation.

Democrats have promised expansive new economies around technology and green energy, but badly underperformed. The Public Policy Institute’s Bohn sees room for more retraining of the existing workforce, as well as a need to push future technological development in the direction of creating jobs rather than making them obsolete.

Sragow sounded an alarm for far greater focus on aligning public school education with the realities of the state economy, better preparing millions of students for the workforce.

Newsom has been neither as horrible as his harshest critics contend nor as successful as his ardent supporters claim. He deserved the pummeling he got for his French Laundry blunder, dining out in style while telling people to stay home. The employment benefits scandal was an embarrassment, and it’s unforgivable that nursing home patients and workers died in great numbers early in the pandemic without quicker intervention.

And yet, though Newsom wasn’t always consistent in managing the pandemic and the interests of small-business owners, California is far better off than other states.

In the latest polling, Newsom’s job seems safe — despite stumbles, his positions on major issues such as climate change and public health are in line with a large majority of the electorate. But in a time of such polarization, incivility and institutional collapse, who can believe public polls?

If Newsom loses, we’re in for an adventure.

If he wins, rather than take a victory lap, he should take heed.

California’s problems have festered for decades, and it’s time for someone to lead.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.