COVID-19 vaccinations lagging despite FDA’s full approval of Pfizer shots

Scientists and officials have long hoped full government approval of a COVID-19 vaccine would help allay stubborn concerns about the shots’ safety and perhaps trigger a new boost in inoculations among those who have been hesitant to roll up their sleeves.

But so far, there hasn’t been an obvious uptick — nationally or in California — following the Food and Drug Administration’s full approval of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine for people 16 and older, according to a Times analysis.

Nationally, there were 2.91 million people who had received their first dose of a COVID-19 vaccine for the seven-day period prior to the FDA’s announcement on Aug. 23. But instead of a surge in vaccinations for the week of Aug. 23, there were actually slightly fewer first doses of vaccines administered: 2.78 million, representing a 4% decline.

There was a 6.5% decline in weekly vaccinations in California; from Aug. 16 through Aug. 22, about 326,000 first-dose vaccinations were administered, but the following week, about 305,000 were given.

Before the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine was fully authorized, it was distributed under an emergency use authorization, which is still the case for the Moderna and Johnson & Johnson vaccines.

Health officials in several California counties confirmed they haven’t seen an increase in vaccinations since Pfizer’s full authorization.

“We haven’t seen a boost here,” Los Angeles County Public Health Director Barbara Ferrer said last week.

There were 75,526 first-dose administrations in L.A. County between Aug. 16 and Aug. 22, and 68,332 the following week. Health officials say that more recent data can sometimes appear artificially low, as it takes time to account for all doses given on a particular day.

Santa Clara County, Northern California’s most populous, reported 9,310 first-dose vaccinations in the week before the FDA’s announcement, and 8,515 first doses for the seven-day period after.

“We did not see a bump in our first doses,” said Dr. Sara Cody, the county’s public health director and health officer.

The pandemic is now hitting hardest in the San Joaquin Valley, the Sacramento area and rural Northern California, in terms of per capita hospitalizations.

It’s important to note, though, that some areas may simply be running short of people to vaccinate. In Santa Clara County, the home of Silicon Valley, 88% of residents 12 and older are at least partially vaccinated. Santa Clara County has one of California’s highest vaccination rates.

But even areas with much lower vaccine coverage — like Fresno County, where 63% of residents 12 and older have received at least one shot — did not see a boost in vaccinations after full approval of the shot.

Before the FDA’s announcement, Fresno County reported 11,313 first-dose administrations over a seven-day period. Afterward, 10,622 first doses were given.

Authorities think there are still many unvaccinated people who eventually will get vaccinated. Some, like those who work multiple jobs, may opt to get the shot if an opportunity comes to them. Others may change their mind if they or someone they know becomes infected with COVID-19.

Some areas and demographic groups that were hit hard earlier in the pandemic by severe disease are now reporting higher vaccination rates, in part because of successful, culturally competent public health strategies. For example, Native Americans now have a higher vaccination rate than any other major racial or ethnic group. Imperial County, an impoverished, largely agricultural county on the Mexican border, has one of California’s highest vaccination rates.

Across the state, rates of vaccinations among Black and Latino residents have generally lagged behind white and Asian Americans. But in San Francisco and Santa Clara counties, rates of vaccinations among Black and Latino residents are now essentially at least equal to those of white residents.

COVID-19 vaccination rates are significantly lower among L.A. County’s younger Black and Latino residents than for other racial and ethnic groups.

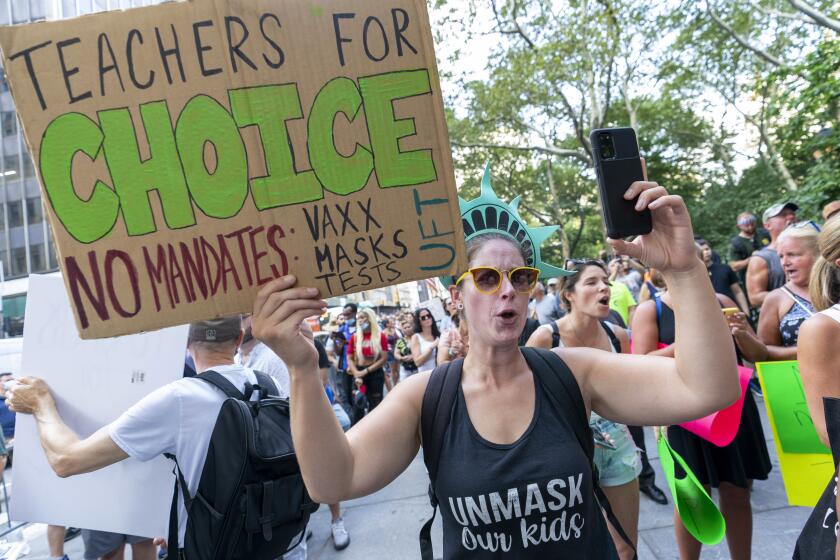

Some officials also note that it may be difficult to persuade those most vociferously opposed to vaccinations.

A recent Kaiser Family Foundation survey found that while 67% of surveyed U.S. adults said they were vaccinated, and 3% said they’d get vaccinated as soon as they can, about 30% said they were unvaccinated.

Of all surveyed adults, 14% said they will definitely not get the shot, while 10% said they wanted to “wait and see” how the vaccines work for other people, and 3% said they would get vaccinated only if required for work or school.

“Younger adults (18-29 years old), Republicans, rural residents and the uninsured still report lower rates of vaccine uptake than other demographic groups,” the survey said.

With a student vaccine mandate, L.A. Unified would once again be stepping ahead of most other school systems in its measures to protect against COVID-19

One reason for the persistent gap, the survey found, is that unvaccinated adults “are more likely to say they are not worried they personally will get seriously sick from the coronavirus and to believe that getting the vaccine is a bigger risk to their own health than getting the virus,” while 88% of vaccinated adults say that a coronavirus infection is a bigger risk than getting the vaccine.

Most unvaccinated adults responding to the survey said they think the news media exaggerated the seriousness of COVID-19, while most vaccinated adults said the news media was either correct or underestimated the seriousness of the pandemic.

Officials say they remain focused on eliminating practical barriers to vaccine access as well as meeting people where they live and trying to address their concerns directly.

“While we’re grateful for everyone who has been vaccinated, we must continue to explore ways to talk to each other about the vaccines that communicate the reality of their safety and effectiveness, and that invite people in rather than pushing them out,” Ferrer said.

In California’s Central Valley, hospitals are filling with COVID-19 patients and health officials are raising alarms, saying things could get worse.

Although there doesn’t appear to have been a boost in vaccinations related to the FDA’s announcement, weekly vaccinations did begin increasing in July as the Delta variant surged nationwide — pushing the nation into a fourth wave of the pandemic that continues to strain hospitals across the country.

Nationally, administration of vaccine first doses doubled between early July and early August, rising from an average of 222,000 first-dose injections a day for the week that ended July 8 to 477,000 first doses a day for the week that ended Aug. 9.

By the last Saturday in August, the U.S. was averaging about 397,000 first-dose shots a day over a weekly period.

A similar effect was seen in California. For the week that ended July 9, California was recording about 30,000 first-dose vaccinations daily; by the week that ended Aug. 9, California reported about 51,000 first doses a day.

More recently, California was recording about 44,000 first-dose administrations a day over the weekly period that ended on the last Saturday in August.

L.A. Times data show coronavirus cases slowing in the state, led by improvements in Southern California and the Bay Area, but more rural areas continue to struggle.

Despite that progress, health officials warn that COVID-19 will continue to fester unless a higher share of the population gets vaccinated.

In L.A. County, Ferrer is hearing from healthcare workers caring for severely ill adults — many of whom are parents.

There are also deaths occurring among some “unvaccinated young adults who opted out of vaccination because they didn’t think the virus was a threat,” she said. “They are the ones we must reach if we’re to end this pandemic.”

Los Angeles County has reported a greater number of unvaccinated people who are younger and otherwise healthier filling hospital beds.

Among adults and the oldest teenagers who are hospitalized with COVID-19, the median age of unvaccinated or partially vaccinated patients was 51. That’s notably younger than the median age of fully vaccinated patients in the hospital with COVID-19, which was 66.

Fully vaccinated people also were less likely to need admission into the intensive care unit or to have such difficulty breathing that they need to be sedated and have a breathing tube inserted.

At Fountain Valley Regional Hospital in Orange County, the average age of people admitted for hospital treatment in January was 64. Now, it’s 46, Dr. Timothy Korber, the hospital’s medical director of emergency services, said recently.

Dr. Rais Vohra, Fresno County’s interim health officer, said people are “in so much danger if you’re not vaccinated right now.”

“We really are seeing just many, many people that are unvaccinated — young people, in their 20s, 30s and 40s — that are landing in the hospitals right now,” Vohra said. “That could be you. That could be someone that you love, someone that you know.”

No major religions denounce vaccination. That hasn’t kept individual churches from providing religious “cover” for those seeking to avoid jabs.

In Orange County, “the overall pattern is that it’s the 30-, 40-, 50-year-olds who are getting hospitalized, compared to previous surges when it’s really been 65 and over,” Dr. Regina Chinsio-Kwong, a deputy health officer, said at a briefing last week.

“If we don’t take care of this pandemic and get people vaccinated soon enough, the unvaccinated will basically allow a new variant [to emerge] that’s even more dangerous,” Vohra added.

Some health experts suggested that other local governments in California pursue mandatory requirements for customers of indoor restaurants, bars and gyms to show proof of vaccination to enter, something San Francisco and Berkeley have done.

The Los Angeles City Council is weighing a similar requirement, while members of the L.A. County Board of Supervisors signaled recently they were in no rush to do so, given improving pandemic trends.

“Bottom line: Vaccination requirements work,” Jeff Zients, the coordinator of President Biden’s COVID-19 task force, said during a briefing. “They drive up vaccination rates, and we need more businesses and other employers — including healthcare systems, school districts, colleges and universities — to step up and do their part to help end the pandemic faster.”

Mu, a coronavirus variant labeled a “variant of interest” by WHO, has been detected in 167 people over the summer in Los Angeles County, officials said.

Biden recently called on employers to require their workers “get vaccinated or face strict requirements.”

“Vaccination requirements have been around for decades,” he said. “Students, healthcare professionals, our troops are typically required to receive vaccination to prevent everything from polio to smallpox, measles, mumps, rubella.”

In late July, Biden also announced that more than 2 million people employed by the federal government will be required to wear masks, physically distance from others in the workplace and get tested regularly unless they’ve been vaccinated.

The U.S. Defense Department has also ordered military troops to get vaccinated.

“To defend this nation, we need a healthy and ready force,” Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin wrote in a memo. “After careful consultation with medical experts and military leadership, and with the support of the president, I have determined that mandatory vaccination against coronavirus disease ... is necessary to protect the force and defend the American people.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.