Ulysses Sandoval was desperate to save his dog.

Chia needed surgery to remove a large stone in her bladder, but Sandoval had lost his job during the COVID-19 pandemic. He had asked family members for help and was ready to take out a loan and sell his car to come up with the $2,200.

Frantically calling rescue groups, he dialed the L.A. County animal care center in Downey. A staff member said he might be eligible for a $500 voucher.

Giving up Chia “would have been my last, last option,” said Sandoval, 25. He suffers from anxiety attacks, and Chia — a 10-pound poodle mix — calms him.

The voucher, which Sandoval obtained this past spring, is part of an approach called “managed intake” now being used at the seven animal shelters run by Los Angeles County.

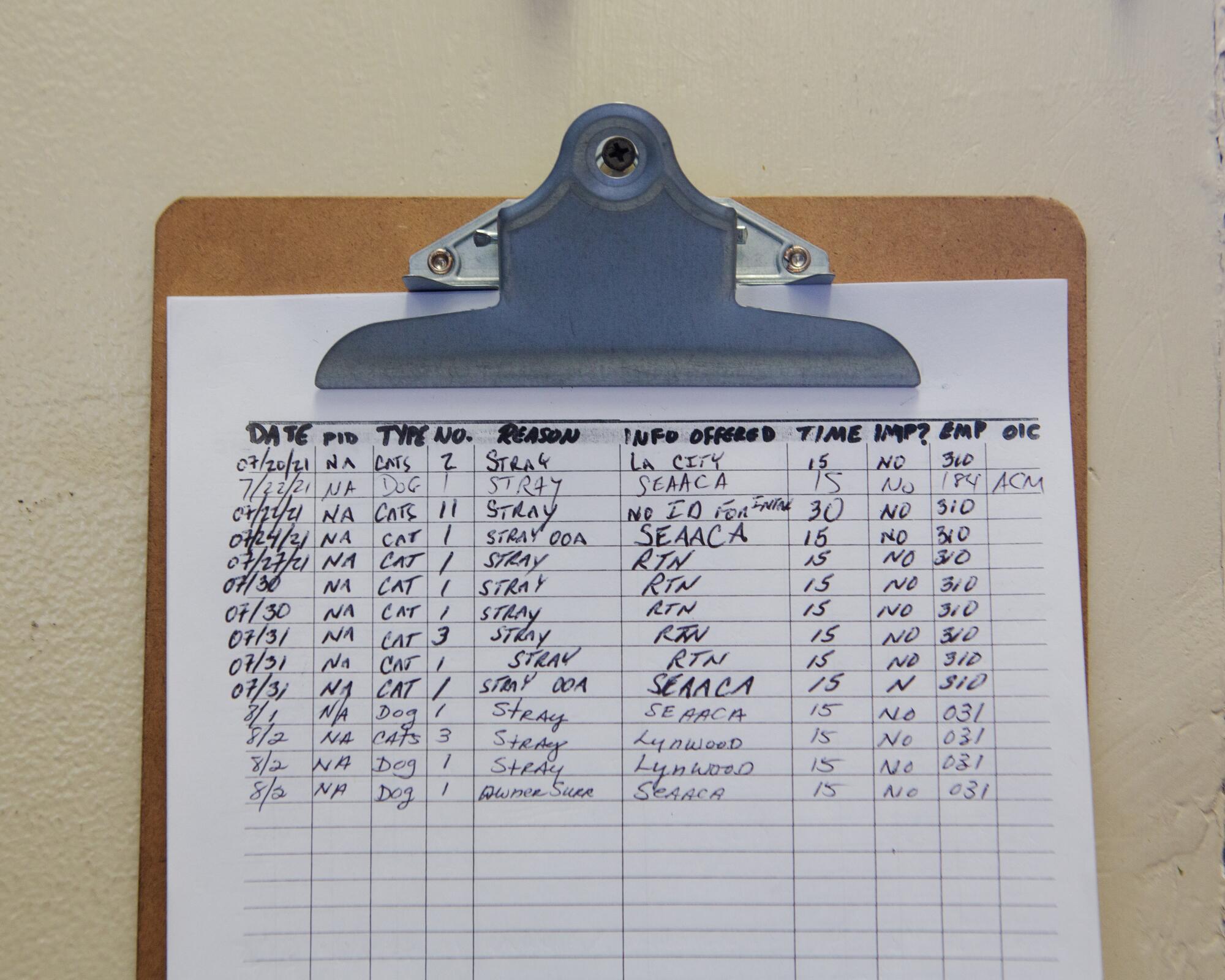

People who want to relinquish their dogs or cats must have an appointment, rather than just stopping by during business hours. Shelter workers then assess whether they can help the pet stay with its owner by providing assistance with veterinary bills, food, supplies, boarding or training for behavioral issues.

If those options won’t work, owners are advised to look for another home, though the shelters will still accept the animals as a last resort.

People interested in adopting are also required to have an appointment.

To proponents, including the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, managed intake helps pets stay in their homes while reducing the head count in the largest shelter system in the country.

The goal is to accept only sick, malnourished, injured, neglected or dangerous animals, as well as those whose owners are facing an emergency or have exhausted all other options.

“It was easy for us to take in animals, but it was always difficult for us to get them homes,” said Sgt. Chris Valles at the Palmdale Animal Care Center.

But critics say that some pet owners are no longer willing to care for their dogs or cats, raising concerns about the fate of those animals once they’re declined at the shelters.

Requiring appointments for adoptions also could result in fewer animals finding homes, critics argue.

The county shifted to managed intake early in the pandemic because its shelters were closed to the public, offering an opportunity to test the strategy.

Fewer than 25,000 dogs, cats and other animals were taken in at L.A. County shelters in the 2020 fiscal year, compared with more than 46,000 the previous year — proof of the new program’s success, its proponents say.

In less crowded shelters, the animals that remain are happier and less stressed, said Marcia Mayeda, director of L.A. County Animal Care and Control. And employees have more time to care for them.

“We should be the last choice,” Mayeda said.

About half of shelter systems in California adopted some form of managed intake during the pandemic, said Dr. Cynthia Karsten, outreach veterinarian at the UC Davis Koret Shelter Medicine Program, who helped L.A. County implement its program.

Orange County has been practicing managed intake for the last few years, and L.A. city shelters recently adopted a hybrid version, requiring appointments while still accepting all animals.

L.A. County officials say they see many people like Sandoval who don’t want to surrender their pets but cannot afford hefty vet bills.

Earlier this year, in response to pandemic-related job losses, the county started the grant-funded voucher program that paid for Chia’s surgery.

“If you come to our doors and you say, ‘I’m turning in Fluffy because she has an ear infection, and I can’t afford to fix it,’ or ‘I’m getting put out of my house, and I don’t have anywhere for her to go for two weeks,’ or ‘I don’t have any food,’ we can help you with all of that,” said Lanette Montez, who leads the county animal shelters’ outreach team. “You keep Fluffy. We don’t want Fluffy.”

Since managed intake was rolled out systemwide in L.A. County shelters, owner surrenders have fallen by 58% for dogs and 68% for cats.

The euthanization rate for cats has dropped from 48% to 31%. The live release rate for cats, which includes animals that were adopted, transferred to rescue groups or returned to their owners, has increased from 54% to 68%.

The numbers for dogs have stayed fairly steady, with euthanization going from 12% to 11% and live release remaining about 88%.

There is no formal timeline for when an animal is euthanized, and “each animal is looked at as an individual,” said Don Belton, the county animal control spokesperson.

Karsten, the UC Davis veterinarian, said crowded animal shelters are a symptom of larger problems, such as poverty and societal inequities.

Managed intake allows staff to help people with those issues and also keep their pets, while reducing euthanasia.

“Everyone will tell you what a relief it is to come to work and feel like I can do what I’m here to do,” she said.

But Alison Eastwood, whose Eastwood Ranch Foundation rescues animals from high-kill shelters, said volunteers at county shelters have nothing good to say about managed intake.

They worry that clerical staff, rather than animal control professionals, are deciding whether to accept a pet and that the burden is being placed on the public to find homes for animals.

Some animal rescue groups say that owners are increasingly turning to them after being rejected at the shelter.

“With COVID, everything has gotten worse,” said Cyndi Zacko, the director of Carson Cats Rescue. “People losing their jobs and lack of donations have really made it hard for us to help all the people that contact us.”

In the Antelope Valley, Paw Parent Animal Sanctuary is getting four times more emails and calls since the county implemented managed intake.

Dusti Hutchings, an adoption specialist at Paw Parent, said she hates turning on her computer each day and being met with emails from people who have found cats, brought them to the shelter and been turned away.

“We’re just bombarded every day with people trying to give up animals we don’t have room for,” she said.

Lisa Avery, an attorney and cat rescuer who has volunteered at the Baldwin Park and Carson shelters for years, said she and other rescuers have witnessed people dumping house cats at feral colonies since managed intake started.

“I don’t think we should say, ‘Oh well, these newly abandoned cats will figure it out — the feral cats will show them the ropes,’” Avery said.

Karsten said it is understandable to be concerned about these animals, but shelters are not the right place for them.

Other animal rescuers are protesting the appointment requirement for viewing animals at the shelters, out of concern it could reduce adoptions.

An online petition has attracted more than 5,000 signatures and the attention of celebrity animal-lovers, including actress Katherine Heigl.

“The primary purpose of our shelters, the reason for their existence, is to find homes for the animals that are sheltered there,” Heigl wrote on Facebook. “It is not to make things as easy as possible for the employees and staff.”

County officials argue that the previous open-door policy not only overburdened the staff but also stressed out the animals, because the public treated the shelters like a “free zoo,” Mayeda said.

In less crowded conditions, respiratory illnesses have decreased by 53% for dogs and 82% for cats, according to the county.

But L.A. County Supervisor Janice Hahn said constituents have been calling her with concerns about the appointment system.

Appointments at some shelters typically have needed to be made a week in advance, contributing to a 51% no-show rate. County officials are adding more slots to cut down the wait time.

On a recent day at the Downey shelter, Jennifer Zavala arrived to find a companion for Bailey, her 6-year-old Chihuahua and Jack Russell terrier mix.

She and her boyfriend didn’t have an appointment.

Animal control officer Scootisha Thompson borrowed Zavala’s phone to show her how to reserve a time, but the website was loading slowly.

The couple left but kept trying the site, securing a slot for later that day. They took Riley, a 3-year-old Jindo mix, home with them.

“I don’t like it because it is difficult to get an appointment, but I do understand why it is in place,” Zavala, 21, said.

A family with a small child came in without an appointment. There were some no-shows, so Thompson let them into the kennels to look at the dogs.

Later, Kavar McDaniel arrived at the shelter. He had booked a time to meet a year-old brown terrier mix he had seen online.

She was his first dog.

In her new home, Zona zips around, greets everyone and is allowed to sleep wherever she wants.

“It is going amazing,” said McDaniel, a 25-year-old elementary schoolteacher. “She is perfect.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.