Trinity Padilla, 13, stood on the bed of a 1957 Chevy truck that her older brother, Saul Razo, is restoring. Behind her sits her mother’s sunset orange-and- gold 2000 Lincoln Town lowrider, riding high on its back tires equipped with custom hydraulics.

Clearly, Trinity isn’t old enough to drive her own customized car. Instead, she’s content to focus on what’s in the truck’s bed: her all-chrome, lowrider bicycle with twisted accents and a velvet seat.

“I’m not finished yet, but I’m putting it all together,” said the National City, Calif., teenager.

Lowbikes, lowriders and classic cars are more than just a hobby for the South Bay family. They represent a multigenerational lifestyle and an important form of cultural expression.

“My dad had his Chevy Monte Carlo and I was 14 [years old] in a 1964 Impala. Now, my kids are all into it,” said DeAnna Garcia, the 48-year-old mother of Padilla and seven others. “I knew that putting them into this culture — of working hard, attention to detail and looking out for each other — would occupy their time when I couldn’t occupy their time. It was my weapon against drugs and gangs.”

There’s one thing missing, she added: cruising as a family down Highland Avenue, just as she used to in the 1980s before National City outlawed the popular pastime in 1992, saying it caused traffic congestion and crime.

Garcia and a group of local lowrider car club members, who formed the United Lowrider Coalition, are now advocating for the law’s repeal. They’re set to present their case on Thursday during a virtual public forum hosted by an ad hoc lowrider committee that includes members of the coalition and the Community Police Relations Commission, as well as Mayor Alejandra Sotelo-Solis and Councilwoman Mona Rios. The City Council is expected to discuss the future of the ordinance later this year.

“The coalition’s goal is to repeal the ordinance and we want to work with the city and law enforcement,” said member Jovita Arellano. “This isn’t just for National City car clubs; it’s for all San Diego car clubs because everybody loves to cruise Highland [Avenue]. Let’s bring it back and let’s do it right.”

The forum will include a short video and breakout sessions to open a discussion on what the lowriders’ role is in the community, what the culture is and what it isn’t.

“We’re not about gangs and violence,” Garcia said. “We’re about family and respect and hard work.”

Lowriding in San Diego dates to the 1950s, when people gathered to customize vehicles and cruised the area to share the art they had created on wheels, said Alberto Pulido, a professor of ethnic studies at the University of San Diego who co-wrote “San Diego Lowriders: A History of Cars and Cruising.”

Subscribers get early access to this story

We’re offering L.A. Times subscribers first access to our best journalism. Thank you for your support.

Over the years, the lowriding scene grew with the rise of car clubs in neighborhoods such as Old Town, Logan Heights, San Ysidro and National City. During the Chicano Movement, car clubs stood by activists’ efforts that successfully led to the occupation of Chicano Park. Lowriding also became a symbol of resistance for Chicanos who defended and preserved the lowrider culture rather than assimilate into others.

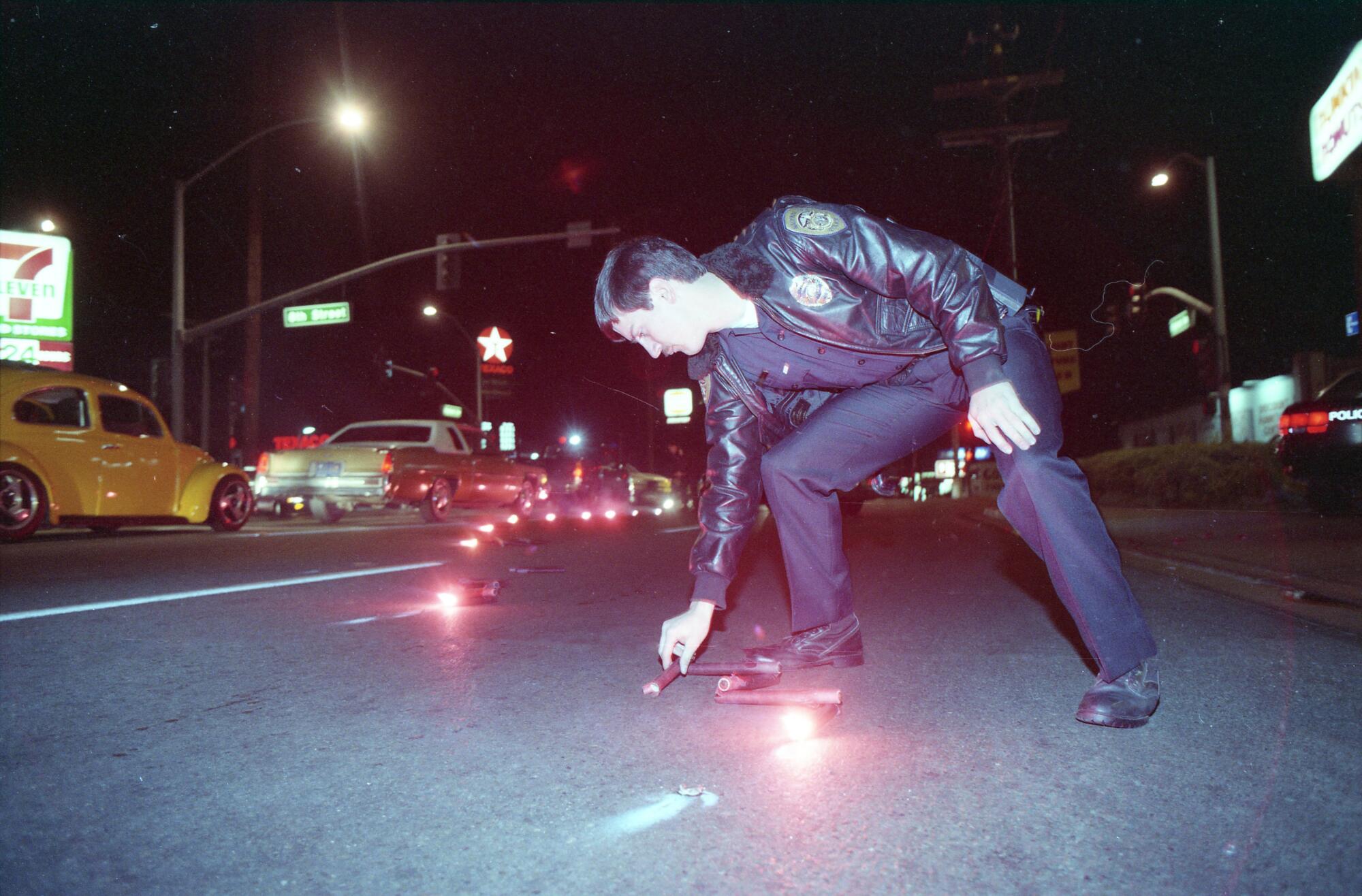

Highland Avenue became a cruising destination, attracting car clubs and even people from outside the lowriding scene from across Southern California. With lots of activity on the street, law enforcement began to put an end to cruising events in the 1980s.

“The cruising ordinance came about in National City years ago because of the problems we were having on Highland Avenue and not necessarily with the lowrider community,” said Police Chief Jose Tellez.

“People would come out to watch these really nice cars driving up and down Highland,” he added. “It sometimes turns into a party scene, which turns into drinking, then assaults, robberies and shootings. We had problems on Highland Avenue in the parking lots and business owners complaining because law enforcement was shutting down Highland to prevent the cruising and customers couldn’t get into shopping areas.”

The police have not enforced the ordinance for years because it takes extra personnel and time to set up checkpoints and “because we haven’t had to. The whole area of Highland has changed drastically over the years, partly because of the ordinance [and] partly because the street has changed,” Tellez said.

Some lowriders said the culture is ever present, just not as it used to be, not only because of the ordinance but because law enforcement had systematically shut down cruising by ticketing riders with “anything they could think of like the tires and hydraulics,” DeAnna said.

To some outsiders, lowriding was tantamount to gangbanging, which some movies falsely portrayed, such as 1979’s “Boulevard Nights,” about street gangs in East Los Angeles, Pulido said.

“I would say it [the movie] played a role in people believing those stereotypes and the reason being is because it had such a negative portrayal of us,” Pulido said. “There was nothing really about who we are as a people, as a community, but it associated lowriding with gangbanging.”

For Sofia Toral, a repeal of the ordinance would mean breaking down those stereotypes and helping pass her culture on to her children.

“I was born into it. My dad had a 1955 Chevy Bel Air and every time he would work on it, I was standing there next to him,” said Toral, who owns an all-purple 1965 Chevy Impala. “The color of the car is the color that I was supposed to paint my grandmother’s nails with just before she passed away. It’s my way of honoring her.”

“Lowriders mean a lot to me, but if cruising is allowed again, it would mean a lot for my kids’ future because it means they won’t have to worry that they’ll get pulled over or get their car taken away, harassed, just for driving a lowrider,” added Toral, who lives in North Park but still frequents National City, where she grew up.

Tellez, council members and car club members have all agreed that tensions between lowriders, law enforcement and government have diminished over time, but there’s room for growth.

“The lowrider community has helped us during our holiday drives, turkey giveaways during Thanksgiving and our Christmas toy drive. We used to make deliveries to houses of families we were going to give turkeys or Christmas gifts to and we had processions that included not only police cars, but lowriders,” Tellez said.

In 1992, National City established a no cruise ordinance to help curb crime and traffic congestion, ending a tradition usually celebrated on Highland Avenue. A group of lowriders have banded together and is looking to have the ordinance revoked.

Sotelo-Solis would like to see three things come out of the forum:

“The first is to continue building the relationship between the city, larger community and our police department,” she said. “ The second is engagement and what our community wants to see event-wise. Who would pay for permits, security and all those efforts? And the third part is to have a discussion about a potential repeal of the cruising ordinance and that builds off of the first two elements.”

The goal is to show that the lowrider community can organize, give back to its community and cruise safely and in harmony within National City, Arellano said. Coalition members said they would like to see National City accept lowriding as part of the city’s long-standing culture without an ordinance just as the New Mexico cities of Albuquerque and Española have done.

In the 1980s, Española adopted the nickname “Lowrider Capital of the World,” and in 2018 the City Council formally declared it a “cruise-friendly municipality.”

“One of the reasons we embraced this was because we did have problems. A few years ago, we had confrontations between the police and cruisers because they weren’t allowed to be in certain parking areas,” said Española Mayor Javier Sanchez. “We wanted to have a great relationship with our police officers and community members, so we found a way to make it work and come together.

“What we did was create spaces for cruisers to go through town and end at a location where they can meet up,” he added. “It’s not a perfect world; sometimes it does interfere with traffic, but when you’re part of a community that embraces the culture and knows everybody, why try and fight it?”

Thursday’s forum will precede a second annual lowrider car show on Sept. 18, which the City Council approved in August.

Scheduled once again from 11 a.m. to 5 p.m. at Kimball Park, the End of Summer Car Show is expected to be a free, family-oriented and non-alcoholic event with a two- to three-hour cruise on Highland Avenue from 24th to Division streets. The event calls for nearly $6,000 in police services, including one supervisor and five officers “because of the size of the estimated crowd and the multiple vehicles in the park,” according to the permit. An estimated 2,000 people could attend.

To join the virtual public forum, visit here.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.