This L.A. woman struggled for weeks to get her family out of Afghanistan. Now they’re out of time

Every time 2-year-old Mubasher hears an evacuation airplane cutting through the sky above his safe house in Kabul, Afghanistan, he runs to the living room window.

“Look, the plane is here!” he calls out to his mother, Madina, in Pashto. “It’s coming to take us to my baba.”

Mubasher’s grandfather lives thousands of miles away, in Los Angeles, where he and his niece Paula Nassiri are desperately working to get their family members out of Kabul.

For the last two weeks, Nassiri, a 46-year-old in Woodland Hills, has dedicated her life to assisting her relatives: her cousin, Madina, Madina’s husband, their two- and seven-year-old sons, Madina’s sister, and their mother, a U.S. resident who was visiting from Tarzana when Taliban insurgents overran Afghanistan’s capital, Kabul, on Aug. 15. Another relative, Nassiri’s stepmother, also is in hiding with Madina’s family.

Members of an Afghan family and the U.S. military recount a massive explosion in Kabul on Sunday.

Nassiri has sent dozens of emails and made even more phone calls, pleading with senators, congressmen, government officials and whoever will listen to help her family flee the war-torn country.

“Their hope is me,” she said. “If they are left there, they are going to die there. Madina’s husband will be executed and he’s the main breadwinner. Their life is over.”

Reached by phone Monday morning, Madina, said she and her family remained in hiding in Kabul. Since the Taliban took over, she and her family have become fugitives, relocating three times. Her husband is a marked man because he last worked for the Afghan government and assisted U.S. armed forces in the rebuilding of the country. According to media reports and eyewitness accounts, the Taliban have been tracking down and targeting Afghan government employees and those who worked for foreign governments or contractors.

“We are living in a very bad situation. … We’re running out of food. We are running out of money,” Madina said. “The Taliban is searching for my husband.”

Since the Taliban takeover, the family has made several futile attempts to reach Kabul’s Hamid Karzai International Airport to escape. Most recently, last Thursday, they gave up trying to gain entry to the airport just a few hours before a suicide bombing attack that killed more than 170 civilians and 13 U.S. service personnel, and wounded scores more.

Madina, whose father served as a translator to the U.S. military and now lives in Tarzana as a legal permanent resident, said she feels that America has abandoned her.

After President Biden announced in April that he would withdraw all American troops from Afghanistan by Sept. 11, Madina’s husband tried to contact several of his former American colleagues for help. He emailed them, asking for a letter of recommendation so he could fulfill the first step of applying for a Special Immigrant Visa for Afghans. But he initially didn’t have much luck.

Also, Madina said, her husband — who asked that The Times not to publish his name — didn’t really want to leave his homeland yet, believing it would take the Taliban months or maybe up to a year to take over Kabul.

He and Madina both speak English and hold master’s degrees. Her husband had a good job and a comfortable life and was hesitant to leave all that behind, she said.

You can help Afghan refugees by donating money to or volunteering with organizations in California.

“He loves his country. He loves the work he was doing,” Madina said. “But everything happened so quickly.”

While Madina, her husband, their children, and Madina’s sister are Afghan citizens, Madina’s mother, the Tarzana resident, is a U.S. green card holder. In June, the mother, who requested anonymity, flew from Los Angeles to Afghanistan to close out affairs in her home country. She planned to sell her property. She also wanted to help her daughters get a U.S. visa and chaperone them out of the country.

That turned out to be harder than they anticipated.

Both Madina and her husband contracted COVID-19, which derailed their back-up plans of finding visas to other countries willing to admit them, she said. She and her husband had planned to visit the Embassy of India to apply for a visa on Aug. 16, but by then it was too late: The Afghan government had collapsed one day earlier.

The day after the takeover, Madina and her family fled their home and went into hiding at their first of three safehouses in Kabul.

Madina panicked when she heard about the chaos that erupted at the Kabul airport as desperate Afghans tried to escape the country, so she and her family decided to stay in hiding until the situation calmed down.

During the first week of Taliban occupation, Madina and her younger sister made several trips in their car to the airport perimeter to check out the situation. Every time it was crowded. She saw her fellow Afghans cajole, plead, and fight each other to get onto evacuation flights.

“How can I subject my two young boys and frail mother to such crowds?” Madina thought to herself. It was too dangerous. They should wait, she thought.

Back in Woodland Hills that same week, Nassiri started her flurry of phone calls and emails to refugee organizations, government officials, local representatives and even Vice President Kamala Harris.

“These individuals are all hiding and fearing execution. They are all well-educated and will not be a burden on the United States,” Nassiri wrote in her pitch to them. She didn’t hear back from most.

Nassiri, a U.S. citizen, fled Afghanistan when she was 8 years old, after the Soviet military invaded the country. Ever since, she said, she has suffered from survivor’s guilt.

Her uncle and aunt left Afghanistan a couple of years ago and relocated to Tarzana, in the San Fernando Valley, after her uncle received a Special Immigrant Visa for his work as a translator for U.S. armed forces.

On Aug 20, an official at Congressman Ted Lieu’s office emailed Nassiri back. He told her that he had forwarded all of the information she had provided to the Department of State’s Congressional liaison unit. He also attached a form letter from the congressman. Lieu’s representative stipulated, however, that there was “no guarantee as to what effect the letter may have.”

With the letter in hand, Madina and her family decided to try their luck on Aug. 22 and headed to the airport. They didn’t get very far.

The family got stopped at the fourth checkpoint, closest to the airport. There, Madina said, the Taliban beat her husband, who had put on a headscarf to disguise himself.

Surrounded by patches of human feces and urine, the family was made to first stand and then sit for hours by the Taliban. Occasionally, a bus would come to pick up a few Afghans in the crowd to take them to the airport. There were thousands waiting, Madina said.

“People were pushing so hard against each other and there was no oxygen. It was very hot,” Madina said.

After 19 hours of sitting and standing, Madina’s mother — who suffers from high blood pressure — fainted and was taken to the hospital. The rest of the family returned home and rested, waiting for Madina’s mother to recuperate.

Last Tuesday, Madina’s husband received news that a congressman had submitted a recommendation for his Priority 2 Visa to the State Department.

Nassiri, in Woodland Hills, and Madina’s husband in Kabul have continued reaching out to anyone who may be able to help them.

“We are in grave danger and hiding from Taliban. They have gone to our previous residence looking for me. Multiple people including the guard in our previous home, our neighbors and my sister who lives on our street gave us the report of them searching for me,” the husband wrote in one email. “Please help my family and my children get out of here alive, PLEASE.”

Madina said her husband worked as a senior engineer for a subcontractor contracted by International Technical Solutions, which was later purchased by Gilbane Building Co. — a construction company that the U.S. government contracted to rebuild key infrastructure for Afghanistan.

Over this weekend, Nassiri connected with Madina’s husband’s former supervisor, Tracy Prill, a 51-year-old who was a construction manager who supervised several projects in Afghanistan for Gilbane.

Prill, now in Arizona, said he is involved in helping several Afghans flee the country, including his former driver who saved his life after a Taliban bombing. Monday, he wrote a letter of recommendation for Madina’s husband. He sent it to Nassiri who then emailed it to government officials.

“There are so many good people that not only kept myself and others safe, they were putting themselves in danger so we could accomplish our mission,” Prill said in an interview. “If it weren’t for them, I wouldn’t be here today, back home in the U.S.”

Prill said he has no doubt that Madina’s husband is in danger.

Wes Cotter, a spokesperson with Gilbane Inc., said that company officials have helped a number of Afghan local workers obtain U.S. visas. He said they are still investigating Madina’s husband claim.

Early last Thursday, Madina and her family ventured toward the airport again, cleared the checkpoints manned by Taliban fighters and somehow made it past the throngs of people to the airport’s Abbey gate, Madina said.

Madina was able to call over a U.S. service member who let her inside the airport.

Madina’s mother handed over her U.S. green card and the letter from Lieu’s office. But U.S. officials inside the airport told the family they believed that their documents were fraudulent and dismissed the stack of paperwork she had, including Lieu’s letter.

After some back-and-forth, Madina convinced the official that the green card was authentic.

“Just your mom can leave,” she said one U.S. official told her. “We cannot help you.”

Madina said she begged, telling the official that her husband had worked with U.S. forces and that his visa was in process.

She said the official then told her: “Get away from the gate. You need to leave.”

Madina’s mother refused to leave without the rest of her family.

“If you are not able to go, I cannot leave you,” she told Madina. “If we die, we die together.”

Madina called Nassiri in Woodland Hills, who urged her to put Nassiri on the phone with the U.S. service members.

“I can explain your situation to them,” Nassiri told her.

Madina, who held on to her toddler, tried to catch the U.S. official’s attention again, but at that moment someone started firing multiple rounds of bullets in the air.

Her son began to scream and cry.

“Don’t be scared,” Madina told him and covered his head. “It’s fireworks.”

The family took a taxi to try other gates and ended up at the gate near the Baron Hotel, but it was too crowded to gain entry.

People pushed against each other. It was hot and Madina could barely breathe.

Some people fell to the ground.

“I saw five women, dead under my feet,” Madina said. “There was no oxygen.”

She couldn’t get any closer to the gate.

“Go to your home or you will die if you get closer to the gate,” one man shouted.

Defeated, Madina and her family went home and collapsed from exhaustion. They woke up a few hours later when they heard the explosion from the suicide bombing.

From their sweltering apartment, Madina said that she and her family are weary and sick with anxiety. During the day, she tries to keep the mood as lighthearted as possible. She smiles for her children. At night and after they fall asleep, Madina sobs.

“What will happen to us?” she thinks to herself. “Will the Taliban come and take my husband?”

Nassiri calls and texts with Madina several times a day to check in with her and try to alleviate her fears.

“All I do is try to give them hope,” Nassiri said.

Madina rarely goes outside and when she does her husband stays behind. Her 7-year-old son, Mudaser, walks with her to buy fresh vegetables and fruit. The last few trips to the banks have been disappointing because many are closed or simply don’t have cash.

On the ground, the once-bustling streets are quiet and empty except for Taliban patrolling with AK-47s in hand. In the sky, the sound of every evacuation flight creates anguish—a constant reminder that one more flight has taken off without them.

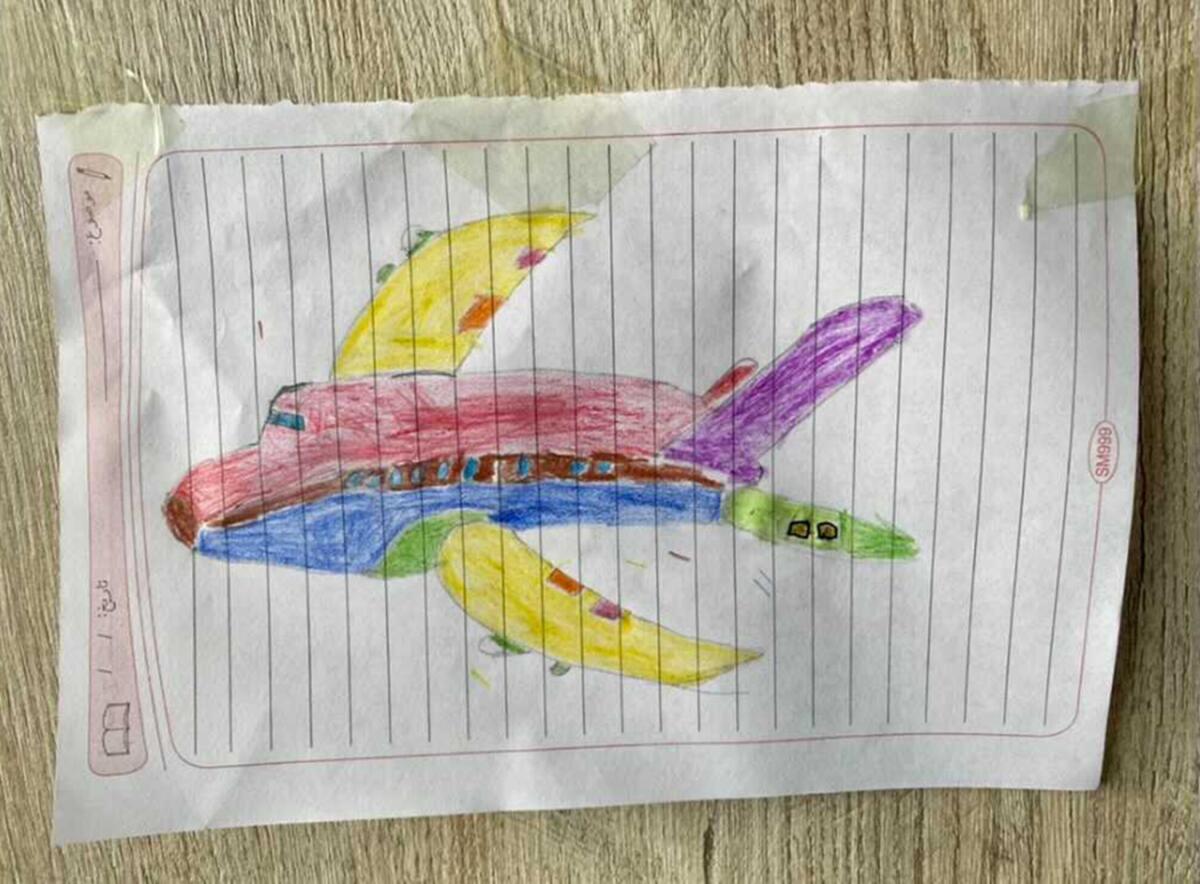

Madina’s children have become obsessed with the airplanes.

Her 2-year-old dances and claps when he spots them in the air. Her older son, Mudaser, 7, now draws his own rendition of the flights.

On Sunday, he sketched one passenger flight with nine windows and yellow wings.

“If we go, we will go on this plane to the U.S.” he told Madina. “It will take me to my baba.”

Staff writer Molly Hennessy-Fiske contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.