California sees signs Delta surge is slowing. New challenge looms

California enters a crucial phase in its battle against the Delta variant this week — the reopening of schools — with some hopeful signs: The number of people being infected and falling seriously ill with COVID-19 is no longer accelerating at dramatic rates and even beginning to flatten in some areas.

Many experts are optimistic over the progress, but some officials stressed it’s too early to know definitively whether the surge caused by the highly contagious strain is peaking.

California is now reporting about 11,800 new coronavirus cases a day over the last week, up 7% from the previous week, according to a Los Angeles Times analysis. That’s a far slower pace of increase than in the previous week, when there was a 30% jump in daily cases, and much better than in early July, when there was an 86% week-over-week increase. Daily cases remain far below the pandemic peak of nearly 45,000 new cases a day.

The rise in COVID-19 hospitalizations is also slowing. California on Sunday reported 7,166 people with COVID-19 in its hospitals, up 20% from the previous week. But that’s an improvement from late July, when there was a 50% week-over-week jump in hospitalizations, and still far below the wintertime peak of 22,000.

Epidemiologists and infectious disease experts credited the combination of better-than-average vaccination rates and local recommendations or requirements to wear masks in indoor public settings as major reasons why the fourth wave has not become as horrific as what’s been seen elsewhere nationwide, such as in Texas and Florida, where hospitals are so overwhelmed they’ve been forced to cancel elective surgeries and have run short of intensive care unit beds.

“Due to the more rigorous application of public health measures, such as strongly recommending or mandating mask use, and the increasing numbers of persons becoming vaccinated, we may very well be cresting in terms of the numbers of cases in California — as compared to other parts of the country — that are still on a major upswing in this fourth surge,” said Dr. Robert Kim-Farley, medical epidemiologist and infectious disease expert at the UCLA Fielding School of Public Health.

Some officials, however, warned it was too early to say that the peak of the fourth wave had passed.

While San Francisco has seen a decrease in daily coronavirus cases, which might have been the result of people increasingly wearing masks, it is “too early to conclude that the fourth surge has peaked or plateaued, and hospitalizations generally peak two weeks after the cases,” San Francisco health director Dr. Grant Colfax said in a statement to The Times.

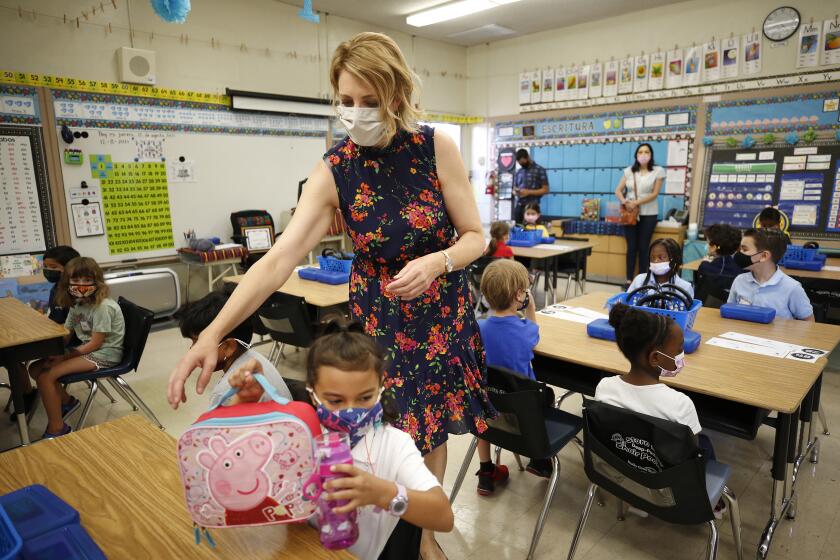

Students returned amid excitement and trepidation — while enduring lengthy waits to get inside campuses

California is still taking steps to prepare in case conditions deteriorate further. The California Department of Public Health is ordering hospitals to begin accepting patients from facilities with limited intensive care unit capacity starting on Wednesday. And Gov. Gavin Newsom has issued an executive order that extends the practice of waiving licensing and certification requirements for out-of-state medical employees assisting in the pandemic response effort.

While the overall healthcare system is not as deluged as during California’s fall-and-winter surge — when roughly three times as many coronavirus-positive patients were receiving professional care — hospitals are feeling the pinch.

“What is really happening is a real challenge with staffing overall,” said Jan Emerson-Shea, a spokeswoman for the California Hospital Assn. “And that is an area that is becoming of great concern across the state.”

Even before the latest surge, she said, hospitals were contending with a backlog of people who had put off non-COVID-related care earlier in the pandemic.

“Now they may need that knee replacement surgery or the gallbladder out,” she said. “Those procedures were starting to come back, and now COVID is rising.”

The Times’ analysis found that coronavirus cases were flattening in multiple regions of California.

In Los Angeles County, average new daily coronavirus cases rose 4% compared with the previous week; the week before saw an 18% jump. Sacramento County recorded a 9% rise; Riverside County, 8%; Orange and Fresno counties were essentially flat.

San Diego County recorded a 5% decrease in daily cases, and the nine-county San Francisco Bay Area observed a 12% drop in daily cases.

Other areas saw higher jumps. Ventura County observed a 13% rise; Kern County, 17%; San Bernardino County recorded a 54% jump.

While vaccination rates have risen recently, the reduction in the severity of the pandemic wave now probably has more to do with greater use of masks and a reduction in riskier forms of social contact. It’s too soon for recently administered vaccination doses to have had an effect, said UC San Francisco epidemiologist Dr. Kirsten Bibbins-Domingo.

“The key here is to recognize we probably are turning the corner, that we can’t just let down our guard so quickly, but we should still feel comforted. Because surges do come to an end, and I think that’s what we’re starting to see now, which is very encouraging,” Bibbins-Domingo said.

Some doctors were optimistic that California’s fourth surge would end up being far milder than in other states where political leaders have opposed mask mandates enacted by local officials and vaccination rates are relatively low.

A boom in COVID-19 hospitalizations for children has been driven by states like Florida, Texas and Georgia, but the numbers in California have been less dire.

The experience in Britain shows that, particularly in a highly vaccinated area, a surge in the Delta variant can hit quickly but also fade relatively quickly, said Dr. Peter Chin-Hong, an infectious disease specialist at UC San Francisco. By contrast, it will probably take areas with lower vaccination rates far longer to emerge from this wave.

At UC San Francisco, the number of COVID-19 patients in the hospital is hovering around 40, up from just five when California fully reopened on June 15. But it’s still far less than the peak during the winter wave, when there were 100, Chin-Hong said.

Hospitalizations have remained steady for the last three weeks, Chin-Hong said. And pediatric hospitalizations remain very low.

Most of the people hospitalized with COVID-19 are unvaccinated, Chin-Hong said. Those who are vaccinated and hospitalized with COVID-19 tend to have compromised immune systems.

COVID-19 outbreaks have been increasing in L.A. County schools and programs in recent weeks, although not to the same extent as during last year’s autumn and winter surge.

San Francisco might be doing particularly well because many residents complied with recommendations and requirements to mask up while indoors. San Francisco also has one of the state’s highest vaccination rates.

When California fully reopened on June 15, “people partied like it was 1999. ... They were not being irresponsible, it was mainly because we were told to go on with life as normal. But once the alarm bell was sounded, pretty much, people in the Bay Area took it to heart — they grumbled, but they did it,” Chin-Hong said.

Chin-Hong credited L.A. County, one of the first local governments in the country to recommend and then require mask use indoors this summer, as properly sounding the alarm that the Delta variant posed a more severe challenge than Alpha.

“It was probably a prescient move ... and probably saved a lot of people getting infected,” Chin-Hong said.

The chasm in coronavirus case rates between unvaccinated and vaccinated Californians is continuing to widen, state data show, as some officials move to require the shots for both work and play.

The Delta variant poses a much more difficult challenge than previous strains of the coronavirus for a couple of reasons. For one, it is far stickier to human cells, like Gorilla Glue, Chin-Hong said. Second, it produces so many more copies of itself — up to 1,000 times more than previous variants.

Vaccinated people are still less likely to get the coronavirus, and less likely to transmit it even if they do get infected, than unvaccinated people, Chin-Hong said. Still, some doctors say it’s no longer considered “rare” for a fully vaccinated person to eventually become infected and, as a result, become potentially capable of transmitting the virus to others, even if they are likely to remain quite healthy.

“Uncommon, OK. Not rare,” tweeted Dr. Robert Wachter, chair of UC San Francisco Department of Medicine.

There’s some speculation that vaccinated people — even though they can have high viral loads at the time of infection, although they generally don’t become severely ill — reduce their viral load much faster than unvaccinated people.

That might help explain why California‘s fourth surge might be much shorter in duration than in other parts of the country, such as Missouri, that have a lower vaccination rate, Chin-Hong said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.