SAN DIEGO — Dressed in leather chaps, an embroidered shirt and a navy blue bow around his neck, Raudel Jimenez adjusts the Virgin Mary prayer card inside the band of his sombrero before strapping down a serape blanket onto his horse’s saddle.

Dust fills the air as dozens of horses are offloaded from trailers into the Pico Rivera Sports Arena in Los Angeles on a recent Friday. Jimenez, of Chula Vista, drove there with a group of fellow charros — cowboys — to compete in the Southern California region charrería state competition.

Charrerías, or charreadas, are Mexican equestrian competitions that consist of roping and riding exhibitions inspired by the daily tasks perfected by charros who used to work in haciendas in 16th century Mexico.

Jimenez is president of Rancho La Laguna, a nonprofit based in the Tijuana River Valley that operates his team, called Charros Rancho La Laguna. He is one of the few guys on the team who got into the sport late, as an adult, so he sticks to the events that don’t require decades of practice, he said recently.

Nevertheless, Jimenez feels the pressure as an announcer describes the performances of the teams ahead. He is full of energy.

“It’s time to get psyched up,” he said to himself.

Minutes later, the 43-year-old rides his horse into the arena at full speed alongside a young bull.

Jimenez bends down onto the side of the horse and grabs the bull’s tail, wrapping it around his right leg. In less than two seconds, he has dropped the thousand-pound animal on its back and is sitting atop his horse, as fans cheer in the stands.

The feat was the part of the competition known as colas, or steer tailing.

Across the United States, dozens of charrerías — which Americans sometimes call Mexican rodeos — bring communities and families to ranches and outside arenas.

Although they are a historic mainstay in Mexico, charrerías are little known in the United States beyond the thousands who participate in them.

The American Charro Assn., which organizes exhibits and advocates for charro groups, said it has about 3,500 active members across the country.

Some charros in the San Diego region, including Jimenez, say they’re working hard to sustain the tradition here, expose people to it and pass it on to their children. They say it is much more than a sport; it’s a display of tradition, culture, skill and courage.

And to Jimenez, it’s also about the clothes.

“Vestirse de charro, es vestirse de México,” Jimenez said: Dressing as a charro is dressing up as Mexico. “You’re wearing your culture.”

Jimenez grew up surfing, but charrería is something that connects him with Mexico, he said.

His father is originally from Jalisco, a western Mexican state where the sport has a strong presence and he often heard stories of other family members involved in charrería.

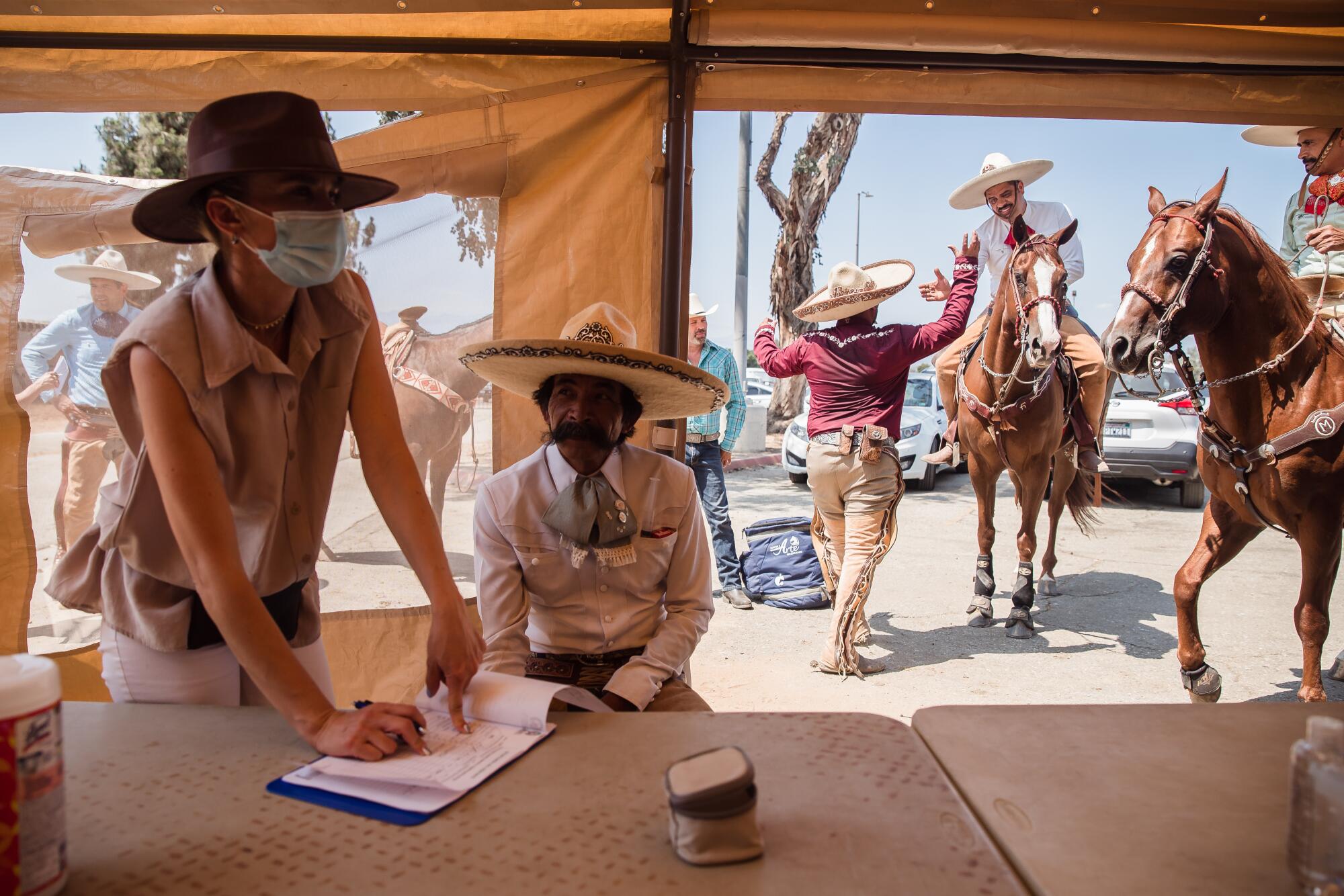

At the recent competition, his teammates with Charros Rancho La Laguna are brushing their horses and securing their leather belts, the men hyper-focused, mentally going over all the details, positions and motions — over and over.

“I try to mentally start seeing myself … competing and doing everything well and perfect,” said team captain Ramon Jara, laughing. “Sometimes that works; sometimes it doesn’t, but at least I want to prepare myself.”

Although Charros Rancho La Laguna gets off to a good start, scoring high points during the first events — called suertes, meaning luck — round after round things fall apart for the team. Later in the afternoon, the men quietly put their horses away after learning they would not move ahead to the next round.

“There’s a lot of variables … that’s why they are called suertes,” said Filemón Jara, Ramon Jara’s brother and team secretary.

Despite the disappointing loss, the Tijuana River Valley-based charro team has a larger mission: to preserve charrería in the region and introduce it to young kids in San Diego.

The Rancho La Laguna team prepares and competes at the Pico Rivera Sports Arena during a charrería competition in Pico Rivera, California. (Andrea Lopez-Villafaña / San Diego Union-Tribune)

Today there are at least 11 charro teams, from Escondido to San Ysidro. The success and visibility of San Diego’s charro community has fluctuated over the years with the availability of large spaces to practice and board horses.

Rancho La Laguna, the nonprofit that runs the Tijuana River Valley ranch, plans to use its space to preserve charrería in the region and introduce it to children.

Ramon Jara understands the value of being exposed to charrería as a child. He grew up in the United States and became a charro at 6 years old. His father passed down the tradition. Now he wants to pass it on to his children.

“It’s part of our roots, part of our culture, part of our blood,” he said.

The day of the competition, Ramon Jara’s 6-year-old daughter follows him around wearing cowgirl boots. She aspires to become an escaramuza — a woman who competes in charrería.

Women compete differently than men; rather than roping events, they ride sidesaddle at galloping speeds in dizzying formations.

Ramon Jara said he likes seeing her enthusiasm, saying it means she’s going to continue the family tradition.

His father, Filemon Jara Sr., was a charro in Jalisco, Mexico. His family owns Rancho La Laguna.

“Being in a country where this is not the norm … for the traditions, kids and families, this is a sport that makes us go back to our roots,” Ramon Jara said.

The sport was often a topic at the dinner table.

Filemon Jara Sr., who still rides but doesn’t compete, said it was important to him and his wife, Ana Maria Jara, to get the next generation involved in the sport in this country where they wouldn’t routinely be exposed to it.

“Pasarlo a otras generaciones quizás para que no se les olvide,” said Filemon Jara Sr., saying the sport needs to be passed down the generations so it won’t be forgotten.

Charrería’s popularity in Mexico rose during the 1920s with the formation of official charro federations, which organize events and oversee regulations. In 1933, charrería was named the official national sport of Mexico.

But its unofficial start can be traced to the 16th century, when the Spanish tasked Indigenous people with herding their horses.

At the beginning the Spaniards did not allow Indigenous people to ride horses, so they developed roping techniques to handle horses and other ranch animals, said Beatriz Aldana Marquez, an assistant professor of sociology at Texas State University. Those techniques eventually were incorporated into the sport, she said.

A charreada consists of nine events that test a charro’s rope skill and athleticism. Each skill performed during the events has an actual use in ranch work, Marquez said.

Some involve rope techniques, such as manganas de pie, where a charro stands at the edge of the arena performing elaborate shapes and tricks with the rope before roping a wild horse by its two front legs.

There is also piales en lienzo, where a charro on a horse throws a lasso at the rear legs of a horse without bringing it to the ground.

Others, such as paso de la muerte, require the charro to jump from his horse to a wild mare, while the other riders chase them around the arena. It’s one of the most dangerous events because if a charro gets knocked off the mare he could get trampled by the other horses.

Marquez — who spent four years researching class, race and gender topics in charrerías in Mexico — said the sport provides American charros an opportunity to feel a sense of belonging. And aside from the competition, charreadas often draw vendors and music and serve as community events, she said.

“Communities that have the charro events really find themselves in spaces where they feel like they are almost back in Mexico because there’s music and mariachi,” Marquez said. “It’s that replica of almost home.”

The Pico Rivera Sports Arena conjured a bit of Mexico that Friday.

The signs in it were mostly in Spanish. Vendors sold charro hats and boots. A taco stand served dozens of spectators and a band played rancheras, fast-paced music that embodies the spirit of heartbreak, horses, love, family and country life.

There were images of religious icons throughout the arena. And the charros, many of whom are Catholic, carried images or small pins of Catholic saints and icons.

Family members and friends cheered on their favorite teams and celebrated successful tricks with wooden noisemakers called matracas, which make a loud cracking sound.

As the last competition geared down with the final team receiving its scores for the paso de la muerte, crowds of people then filled the arena for a dance to fast ranchera music.

The San Diego region has a venue for charrería competitions, but it has struggled. Charros Del El Caballo Park, a charro team in Escondido, has fought for years to preserve its space in northern San Diego County.

Several years ago, the city planned to evict the charro team from city-owned land in northeast Escondido to build water department administration buildings.

But in 2012, a coalition of equestrians, homeowners and charros successfully lobbied the city against building on the site and instead it created a city park that allows hiking, biking and horse events.

Jara sees Rancho La Laguna filling a void in San Diego’s southern region, he said. The ranch has hosted community events, and there are plans to organize activities for nearby schools.

Across the United States, organizations are working to preserve the charrería sport and educate the public about its significance in the Latino community.

Ramiro Rodriguez, chief executive of the American Charro Assn. in Los Angeles, said there is a resurgence of the sport, with more young people getting involved. It’s attractive because it allows children to connect with their culture and build a brotherhood, he said.

“It binds us all together,” Rodriguez said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.