Long a path to success for Korean immigrants, dry cleaners struggle in the pandemic

After graduating from UC Riverside, Edwin Kim drifted in his career, quickly burning out on the e-commerce industry.

He considered helping his parents with their dry cleaning business, but his mother insisted that he go back to school.

He eventually found his niche teaching social science at a junior high school in China.

Meanwhile, his parents are barely staying afloat.

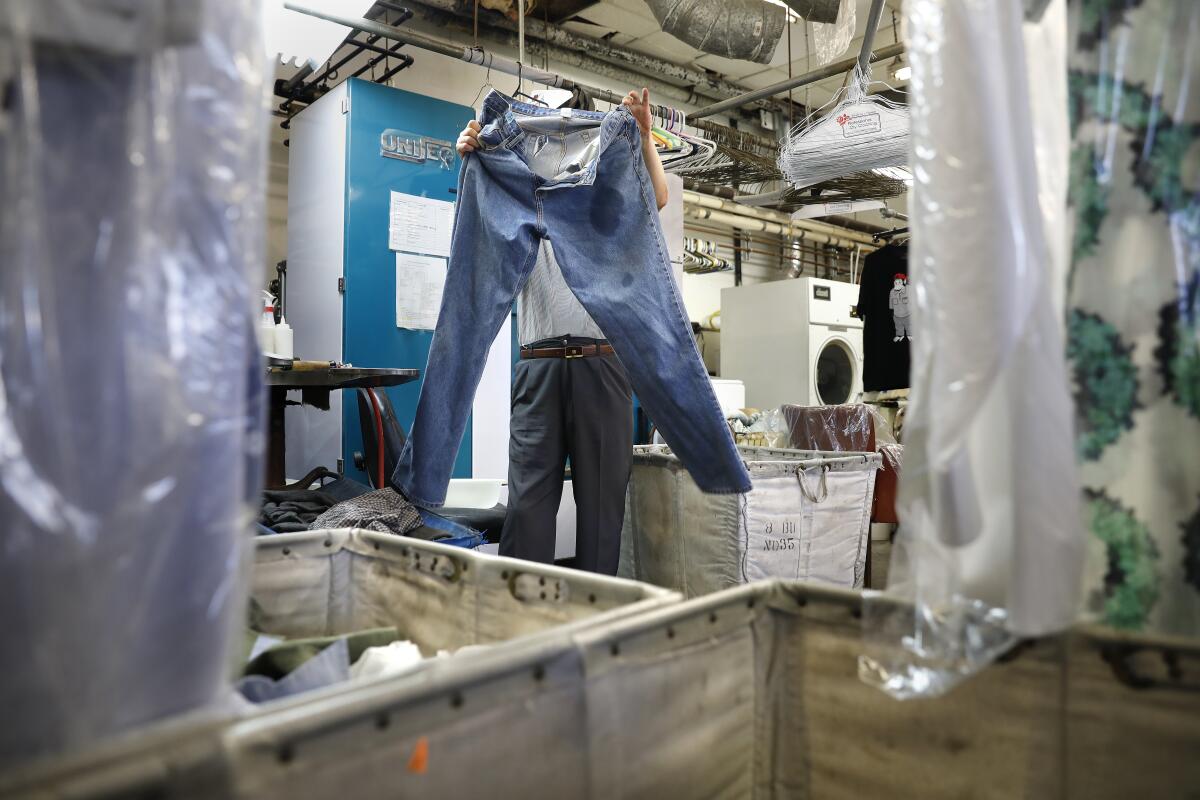

With office workers staying home and weddings and gala fundraisers on hold during the COVID-19 pandemic, only a handful of customers visited Arroyo Cleaners in Pasadena on a recent Tuesday morning.

It is a lonely struggle. But Yoon Dong and Stacy Kim, immigrants from South Korea, would rather their two sons fulfill their dreams than lend a hand with the family business.

“We want better for our children,” said Stacy Kim, 62. “We worked many hours, sacrificed almost everything, so they could do better.”

For many Korean immigrants, owning a dry cleaner has been a path to a better life for the next generation.

Parents worked 13-hour days, fended off irritable customers, inhaled potentially hazardous chemicals. Children did their homework at the store, translated for their parents, sorted hangers and scrubbed clothes during busy stretches.

The receipts from countless shirts, dresses and slacks paid for UCLA, UC Irvine, Stanford and NYU.

These were not family businesses steeped in the hope of a child someday carrying on the tradition.

Rather, dry cleaners were a vehicle to higher education for their children and the careers in medicine, law and teaching that they themselves could not achieve, with their limited English and foreign degrees.

Before the pandemic, the ranks of Korean dry cleaners were already dwindling. The whole point was that there would be no one to take over.

Now, many middle-aged and older immigrants are on the precipice of financial collapse, the future uncertain for dry cleaners as companies weigh permanent work-from-home arrangements and office attire becomes increasingly casual.

In addition to running Arroyo Cleaners, Yoon Dong Kim is president of the Korean Dry Cleaners & Laundry Assn. of Southern California.

At least a quarter of members have closed their businesses since the pandemic began, leaving 800 or 900, he said.

In the late 1980s, he said, about 80% of dry cleaners in Southern California were run by people of Korean descent.

He estimates the figure is now 60% and fears that more closures are likely to follow if the state and county do not renew eviction moratoriums and more financial aid does not flow to small businesses.

Ray Rangwala, a director with the Southern California Cleaner Assn., said at least 50% of dry cleaners from Bakersfield to the border are Korean-run.

At its lowest point, Kim’s monthly revenue was down 80% from last spring. It is still down 30%, and he is worried about what the Delta variant may bring.

The Kims’ journey from new immigrants to dry cleaning proprietors was fairly typical.

They met in 1984 as parishioners at the Los Angeles Korean Methodist Church.

Yoon Dong Kim got a job at a dry cleaner through a church connection. The pastor’s wife, who ran her own dry cleaner, trained Stacy Kim.

“We helped each other,” Stacy Kim said. “We learned from the people in the church. It was Koreans helping Koreans.”

The Kims bought their first dry cleaner in La Cañada Flintridge in 1988, operating it for nearly three decades as they raised their children.

Yoon Dong woke up at 5 a.m. to get the store ready, returning home to pick up his sons and drop them off at school.

The boys spent afternoons at the store. They occasionally helped translate for customers, but their primary responsibility was homework. Edwin, now 31, plans to teach in China long term. His brother, Justin, 33, is a tennis coach.

After selling the business and taking a two-year break, the Kims bought Arroyo Cleaners in December 2019. Yoon Dong missed the routine, while Stacy longed for story-swapping and chatting with customers.

Starting in the 1970s, Korean immigrants welcomed one another into the dry cleaning business with loans, moral support and training, according to a 2015 paper by Ward F. Thomas of Cal State Northridge and Paul Ong of UCLA.

Often, children spent time at the store, but they were expected to concentrate on their studies more than helping their parents, the paper said.

“The children are quite often at the business … it’s a way of supervising them in terms of their education,” Ong said. “It’s still a family business in that sense.”

Tommy Cho got his start in the dry cleaning business through a friend he had known since high school in South Korea, who taught him the basics.

He and his wife, Annie, bought Foxy’s Cleaners in Sherman Oaks in 2000. Their first supplier, also a Korean immigrant, advised them on the latest solvents and machines.

Their only child, Tammy, was in middle school at the time. Her parents dropped her off early and didn’t see her again until well in the evening. When it got busy, she pitched in at the store.

Now 30, Tammy has a sociology degree from NYU and is an immigrant studies researcher for a nonprofit.

During the worst of the pandemic, Foxy’s Cleaners reduced its hours. Revenue was down by 50%.

In December, a state ban on the toxic cleaning agent perchloroethylene went into effect. The Chos couldn’t afford $30,000 in new equipment and switched to wet cleaning.

“We’re a small operation with one employee, so it’s been very rough,” said Tommy Cho, 72.

The Chos got federal pandemic loans for small businesses but still drained most of their savings. The business that put their daughter through college is now reeling.

“My parents worked so hard and supported the family through this store,” Tammy said. “Now they may not be able to retire because of it.”

Chae Yun, 52, who owns Crown Cleaners in Costa Mesa, said 9/11 and the Great Recession were nothing compared to COVID-19.

Soon after Yun arrived in eastern Washington state from Seoul at age 21, a fellow Korean immigrant offered him a dry cleaning job.

After working there for seven years, he bought a store from an elderly Korean couple in 1996, eventually owning several dry cleaners before moving to Los Angeles in 2004.

He and his wife, Young Mi, whom he had met a Korean church, bought Bella Cleaners in Marina del Rey.

They doubled the store’s business in a year, at one point taking in $100,000 a month. But there was a cost. Yun sold the cleaner in 2008 after 14-hour days left him with exhaustion and diabetes.

Three years later, he bought Crown Cleaners. He was too young to retire, and he missed working and running a business.

The Yuns’ only child, Samuel, did well in school and entered UC Berkeley, majoring in data science.

On April 7, during a semester of pandemic-induced distance learning, Samuel killed himself in his bedroom. He was 23.

“I wanted my son to do what he wanted and something other than dry cleaning,” Yun said.

Yun said he wants to speak about his son’s death because of a failure among some Korean immigrants to have meaningful conversations with their children.

He and Samuel shared a similar ethic, working and studying for long periods with little rest. They rarely chatted.

“Korean parents work so hard for their kids, but we can’t forget to appreciate them, to listen to them and to spend time with them,” Yun said.

Yun’s dry cleaning business is at about a quarter of pre-pandemic levels. But he finds solace in the work.

“Dry cleaning and my family is what I know,” he said.

Korean immigrants who provide supplies to dry cleaners have been in dire straits too.

Cleaners Mart in South Los Angeles sells presses, boilers and hydrocarbon machines.

During the pandemic, financially strapped dry cleaner owners stopped coming in to spend $10,000 to $100,000 at a time.

Owner Chan Roh, 66, said business was down about 80% for most of last year.

“Nobody was buying anything,” said Roh, who came to L.A. from South Korea in 1980. “It was scary.”

Roh got by because some dry cleaners took advantage of a rebate for energy-efficient boiler steam traps from Southern California Gas Co. Business has rebounded to about 40% of pre-pandemic levels.

Roh’s son is a teacher in the Irvine Unified School District. His daughter, formerly a teacher, is a homemaker.

“The dry cleaning business ends with me,” Roh said. “That’s OK, because my children are doing something better.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.