Father Joe Carroll, a cheerful Catholic priest whose 40-year devotion to helping homeless people raised tens of millions of dollars and turned him into a San Diego icon, died Saturday night after a lengthy battle with diabetes. He was 80.

Known fondly as the “Hustler Priest,” Carroll took what had been a small charity handing out peanut butter sandwiches downtown in the early 1980s and turned it into an assistance network for poor people that won awards and drew national media attention.

Now called Father Joe’s Villages, it provides housing, food, healthcare, education, vocational training and other services to thousands of people annually.

“This guy touched more lives, did more good for more people, than any San Diegan has ever done,” said David Malcolm, a businessman and philanthropist who served on the villages’ board for 31 years. He said Carroll died at home in downtown San Diego’s East Village neighborhood, where he had been in hospice care after a recent hospitalization.

Carroll built the homelessness organization and made himself a household name through a steady stream of public and private appearances that used humor as a fundraising lubricant. He starred in TV commercials that baldly told viewers, “I want to hustle you out of some money.” He allowed himself to be caricatured on a bobblehead doll, holding a fistful of dollars.

And he avoided using the title “monsignor,” an honorific bestowed by bishops in recognition of exceptional service.

“Everybody wants to help poor Father Joe,” he told the San Diego Union-Tribune in a 2011 interview. “Monsignor Carroll? Who’s that? Anybody who knows anything about marketing knows you don’t want to confuse the message.”

Carroll was born April 12, 1941, in the Bronx, where his entrepreneurial and religious leanings took root early.

He was the fourth of eight children born to Irish Catholic immigrant parents, a father who did day labor and a mother who cleaned offices. Money was tight. He got his first job, in a neighborhood butcher shop, when he was 8. Later he sold Christmas trees and fixed laundry machines.

The local parish was a block away, and Carroll spent many hours there — as an altar boy, in the Boy Scouts, playing sports. Strong at math, an able leader, he developed a reputation as a “goody-goody,” in his words. Everybody told him he would grow up to be a priest.

But he resisted the idea. When he was in his early 20s, he moved to Southern California to escape the cold New York winters and took a job working in a market. One day, while he was sitting on a bench waiting for a friend, a priest walked by. They started talking.

“Next thing you know,” Carroll later recalled, “I was enrolled in the seminary.”

This was at St. John’s, in Camarillo, where Carroll was put in charge of the small bookstore. He added TVs, shoes and other merchandise to the inventory, boosting the shop’s profit but drawing frowns from administrators who concluded he was overly interested in material gain. They expelled him.

“They said I’d be the kind of priest who would sell gold-framed baptismal certificates,” Carroll said. “Hey, if it helps raise money for the church….”

After a short break, he resumed his studies through the University of San Diego and was ordained in 1974. Eight years later, he was working at St. Rita Catholic Church in Valencia Park, content to be a parish priest, when he was summoned to a meeting with Bishop Leo Maher.

The person running St. Vincent de Paul, a thrift store downtown, was retiring. When Maher sought a replacement, he asked members of his clergy personnel board for the name of the biggest go-getter in the diocese. Everybody had the same answer: Father Joe.

Carroll was given a choice. He could take over St. Vincent’s, or move to a parish in the desert, in Needles. He did not want to go to Needles.

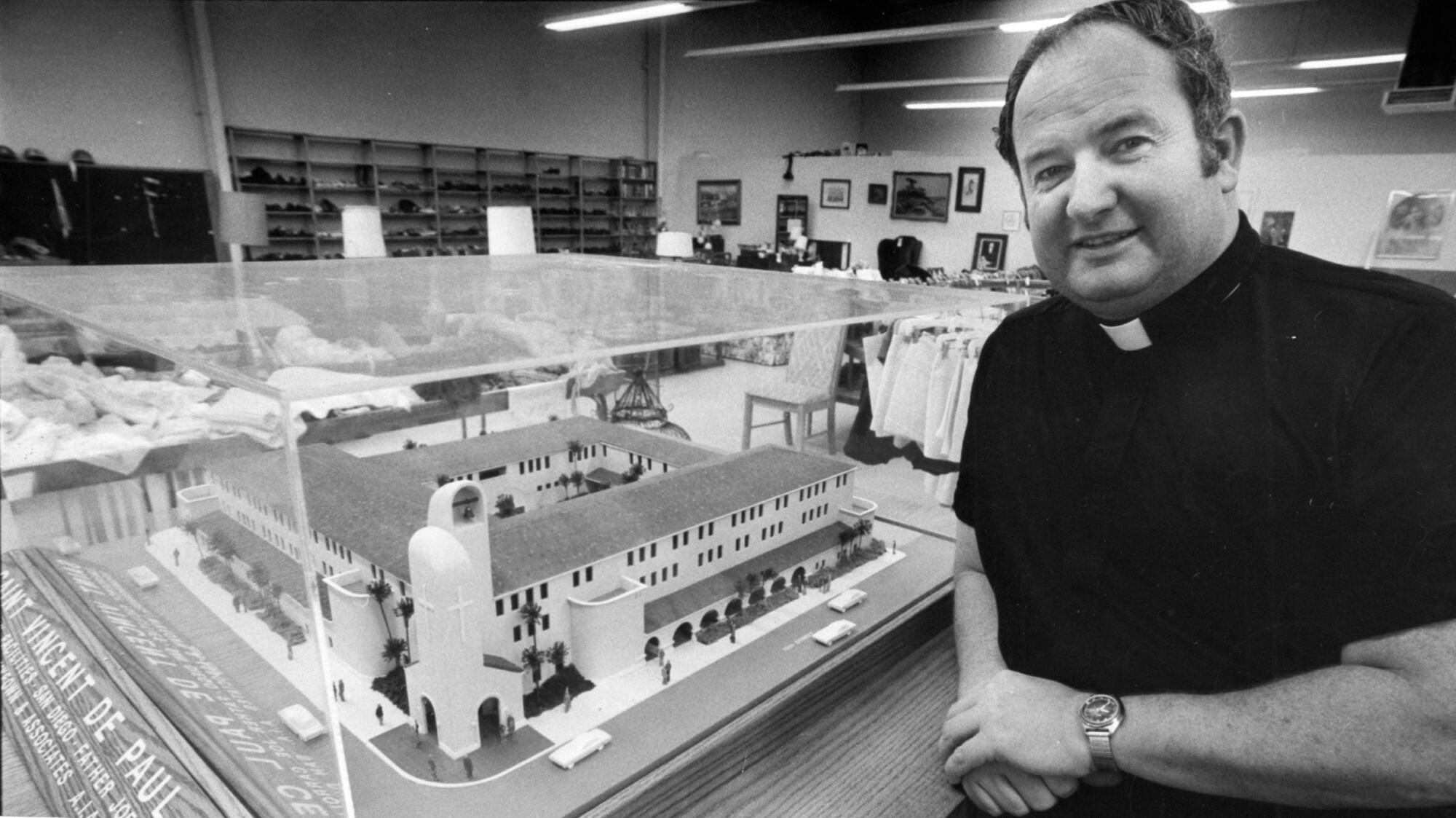

The thrift store had a parking lot nearby that Carroll was tasked with turning into a homeless center. The plan he came up with represented a new approach.

Existing services were scattered around downtown. Why, he wondered, is the health clinic in one place, vocational training in another, and the shelter elsewhere?

He wanted a “one-stop shop,” and over time that’s what he got. St. Vincent’s acquired a property here, a property there, eventually taking over about four blocks in East Village.

Not everyone welcomed the expansion or his comprehensive approach. There were occasional public spats with elected officials who saw the free meals and other programs as enabling homelessness instead of curbing it.

Some property owners and downtown residents felt trampled by what one called Carroll’s “zeal to get what he wanted.” Other homeless-service providers grumbled about his “big dog” status with government funders and wealthy private donors such as Joan Kroc, the McDonald’s heiress.

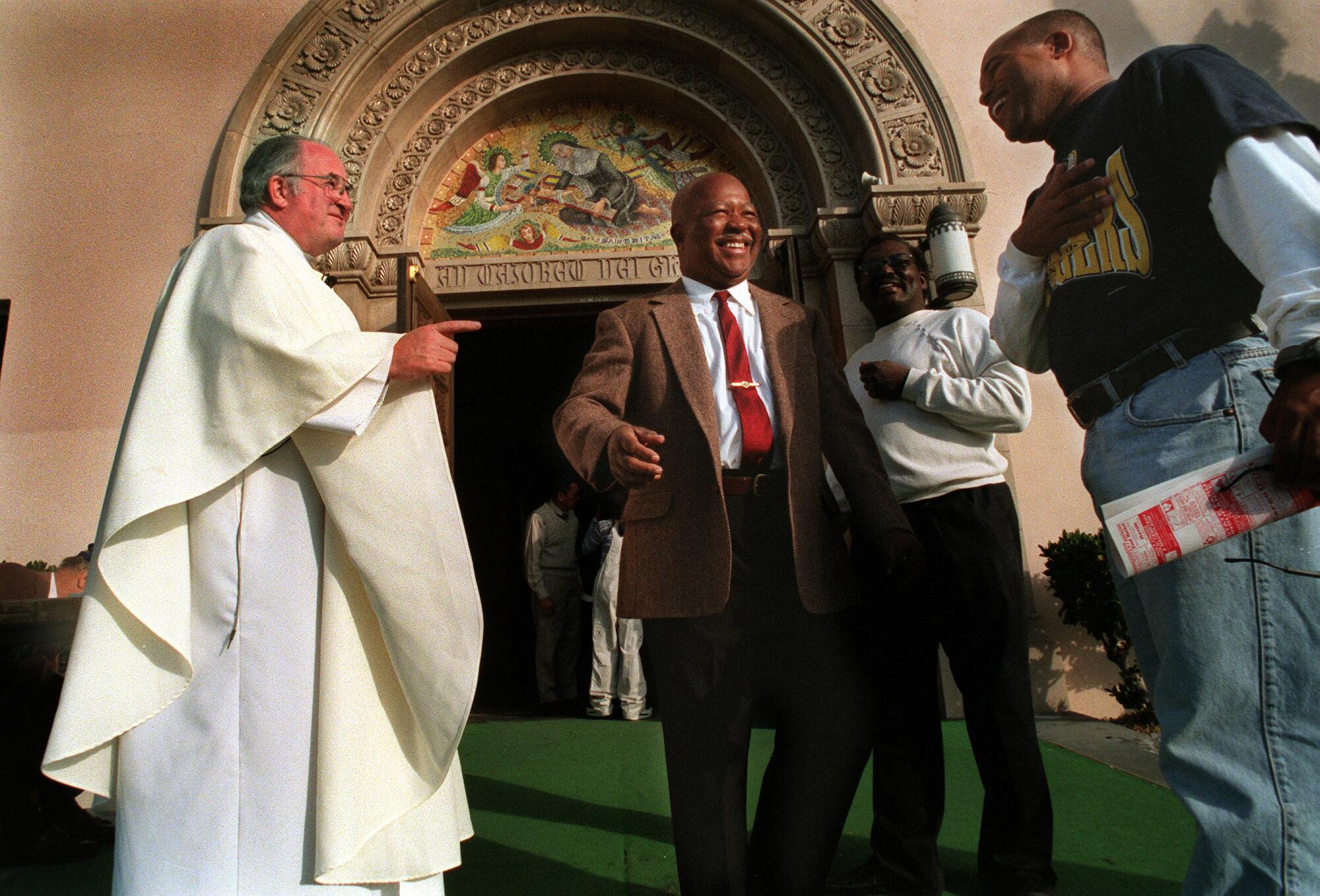

But even the critics respected his success, admired the way he merged the holy with the human, the collar with the quip. Carroll’s smiling gift of gab at society galas and charity auctions tickled funny bones and opened wallets. He once talked a cop who was giving him a ticket for speeding into making a donation.

“He can squeeze money out of a rock,” Monsignor Dennis Mikulanis, a longtime friend, once said.

Every winter, a familiar joke got told, sometimes by Carroll himself: “You know it’s really cold out when Father Joe has his hands in his own pockets.”

Carroll was a fixture on local television and in Union-Tribune columns that highlighted the goings-on of local movers and shakers. He said the opening prayers at countless community events.

Everywhere he went, he urged people to see homeless people as neighbors who were down on their luck, not as deranged or dangerous drifters, and he rejected the idea that they should be housed in rundown buildings. Nice surroundings — courtyards with fountains, beds instead of cots — “send the message that you’re on your way up,” he said.

That approach generated a dig once from the Wall Street Journal, which called the St. Vincent center “Father Joe’s Country Club.” But it also brought plaudits, including a World Habitat Award in 1988 that said the services offered and the environment created enabled clients to “return to mainstream society with self-assurance and dignity.”

And it drew national media attention from “60 Minutes” and Reader’s Digest.

Carroll took his fundraising appeals nationwide, too, in TV commercials asking for donations of used cars, trucks, boats and airplanes. He became so recognizable that people in restaurants and other places asked to have their pictures taken with him. Some were surprised to learn he was a priest, not an actor playing one.

When he wasn’t working, Carroll liked to travel, especially to professional baseball stadiums and on cruises. He stayed active in the Boy Scouts. He gambled occasionally, for entertainment.

He misplaced his white clerical collar so often that his staff bought them in bulk, 100 at a time.

Before health problems curtailed his social life, he hosted parties where the main dish was the cioppino he made. His favorite drink was Pepsi.

He collected Nativity sets, too, amassing about 700 of them — creches made out of wood, metal, stone, cloth. He was fond of ones featuring animals instead of humans because, in his words, “We’re all God’s creatures.”

For many years, the Nativity sets were kept in display cases at St. Vincent’s administrative offices, and the public was invited in during the Christmas season for open houses — where, of course, Carroll asked for donations to help homeless people.

By the time he retired in 2011, on his 70th birthday, St. Vincent de Paul Village had spun off from the diocese into an independent nonprofit with its own governing board. It had about 500 employees and a budget of $40 million.

Even as he stepped away from full-time involvement with the organization, he remained its public face, in fundraising mailers and elsewhere. In 2015 it was renamed in his honor: Father Joe’s Villages.

Diabetes led to amputations of both feet in recent years, and it curtailed his eyesight — but not his zest for telling stories. Earlier this year, he published a memoir, “Father Joe.” In it, he said he’d already written the epitaph for his gravestone, a simple nod to his life’s work: “He was a good priest.”

Information about survivors was not immediately available.

Services are pending.

More to Read

Updates

9:37 a.m. July 14, 2021: This article has been updated with details of a memorial service.

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.