Giving blood has been off limits for many gay men. A new study could help change that

The needle went in easily. Andrew Goldstein sat and waited as his blood, precious and disputed, flowed into the vials.

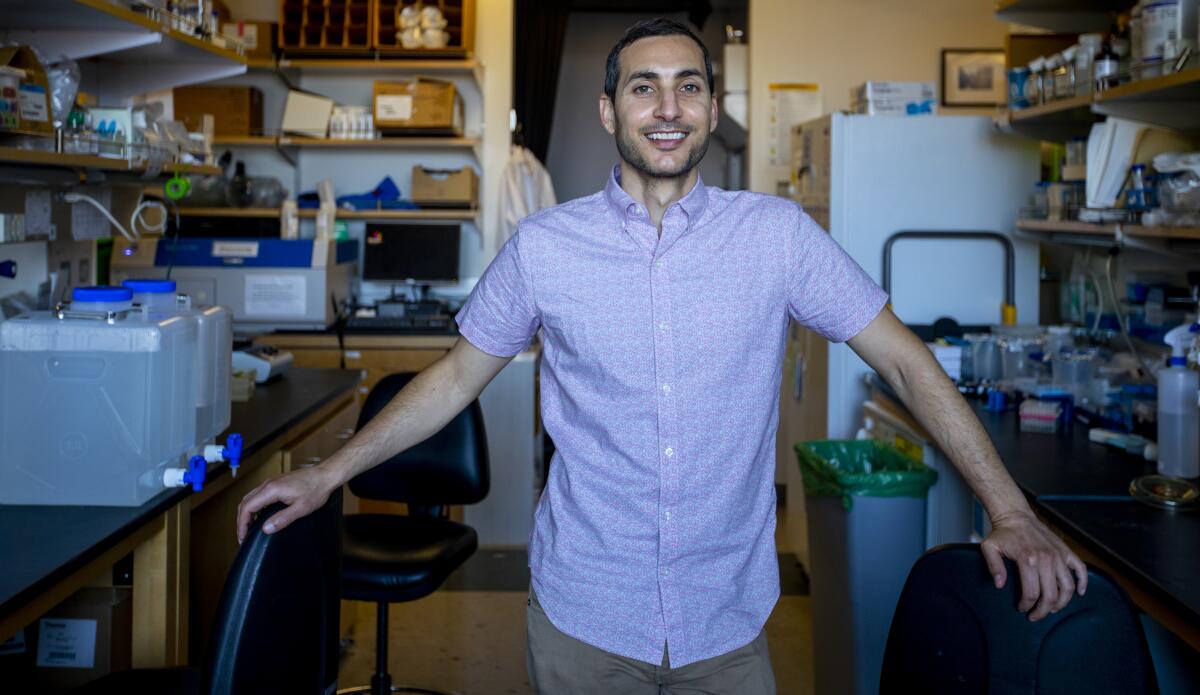

He used to routinely give blood when he was much younger, eager to help save a life. Now the 38-year-old was in a donation center for the first time in years, this time as part of a study that could lead to the changing of a federal rule that has angered and alienated gay men such as him.

“It’s frustrating not being able to help when I’m a healthy donor,” said Goldstein, a biology professor who has been in a monogamous relationship with his husband for more than a decade.

Men who have sex with men have long faced restrictions on giving blood in the United States, amid concerns about the disproportionate toll of HIV/AIDS on gay and bisexual men. Decades ago, as AIDS began devastating gay communities, the Food and Drug Administration advised blood centers to prohibit any man who had had sex with another man since 1977 — even once — from donating.

The FDA, which regulates blood banks, has eased the rules somewhat in recent years. But gay and bisexual men are still ineligible to donate if they have had sex with another man in the last three months.

The federal rules have long drawn protests from physicians, politicians and activists who denounce them as outdated and stigmatizing. Many were especially upset after a mass shooting at the gay nightclub Pulse in Orlando, Fla., when gay men were turned away from giving blood to help the wounded.

Physicians are trying to figure out who should get a new Alzheimer’s treatment, one that has sparked optimism among patients but worry for doctors.

“It’s perpetuating a discriminatory approach that’s not based in science,” said Stephen Lee, executive director of the National Alliance of State and Territorial AIDS Directors. Gay men in monogamous relationships are generally barred, but “what about straight men who are having unprotected sex with women or engaging in other risky behavior?”

Others have argued against loosening the restrictions, saying it is too risky to expand eligibility among a group that has higher rates of HIV infection. When the FDA sought comments, hundreds of people sent in letters asserting that “weakening the protections of America’s blood supply for political ideology puts the safety of Americans at risk.”

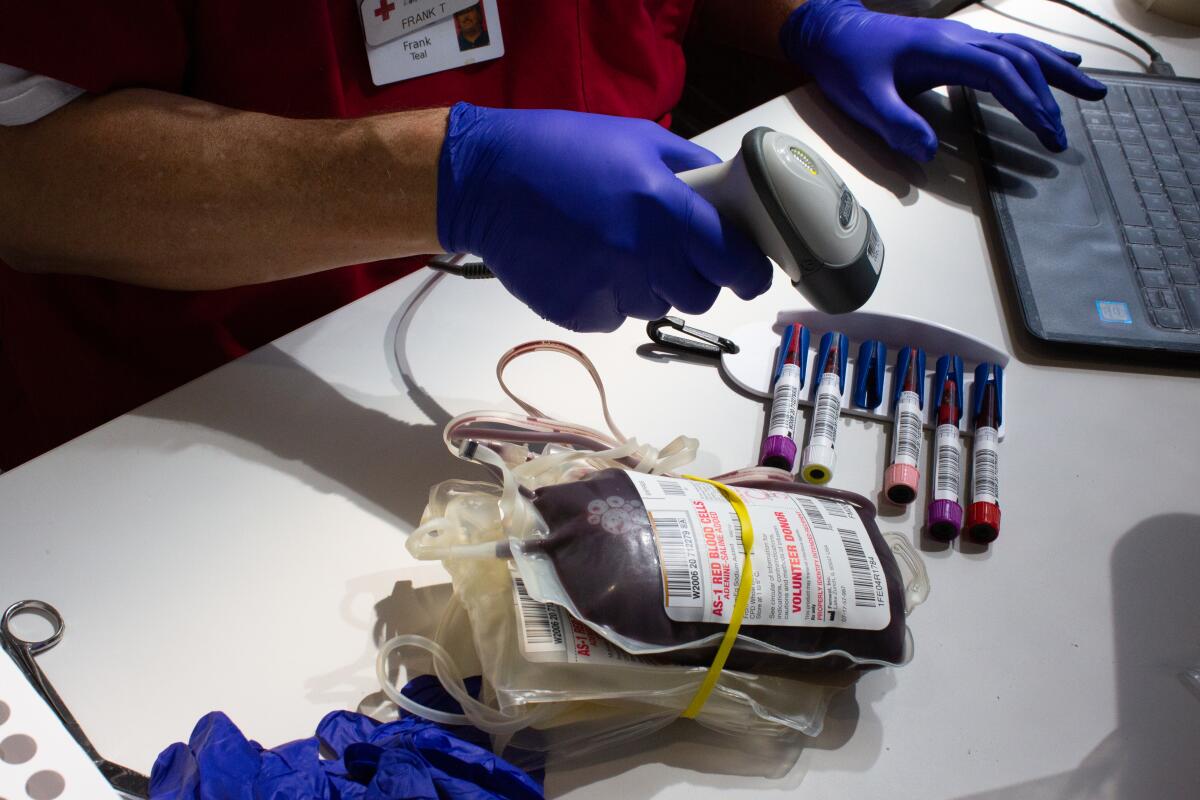

Now blood banks are seeking out gay and bisexual men in cities including Los Angeles, Miami and Memphis for the Advance Study, which aims to find out whether asking would-be donors about risky behaviors — such as having sex without a condom — could be a safe alternative to screening out all men who have recently had sex with men.

Susan Stramer, vice president of scientific affairs for the American Red Cross, said that the Red Cross and other blood banks are interested in reassessing the rules to ensure that “anyone who has an appropriate safety profile can donate.”

“Because testing isn’t perfect, we want to preselect donors who have the lowest risks,” said Stramer, one of the lead researchers on the Advance Study. What the new study aims to find out is whether it would be equally effective to assess risk with specific questions about risk behavior, such as how many sexual partners someone has had recently.

The Red Cross and two other blood centers — Vitalant and OneBlood — are now enrolling sexually active gay and bisexual men in the federally funded study, asking them about risky behaviors, then collecting and testing their blood for HIV. They are aiming to garner 2,000 participants in eight areas, assisted by partners including the Los Angeles LGBT Center.

Among those participants is Goldstein. Before he became ineligible to donate, Goldstein — who has type O negative blood — said he had given blood so regularly that he had been rewarded with a pin as a frequent donor. This summer, after he had his blood drawn for the study at a Pasadena center, he snapped a photo of himself outside and posted it on Facebook.

“When I grew up, it was very clear that as a boy, being gay was the worst thing you could be. The only examples of gay people were people dying of AIDS,” Goldstein said. Since then, “I’ve watched the world change around me” — including legal recognition for his marriage and gay couples living happily on television and in films.

Being barred from giving blood, Goldstein said, seems “totally out of step with where we are.”

Early in the AIDS epidemic, serological testing couldn’t effectively detect the virus until months after exposure. Blood centers were horrified when hemophiliacs who relied on blood products were infected with HIV through transfusions.

“It’s hard to overstate how strong the impact of that terrible time was on blood banks,” said Arthur Caplan, director of the division of medical ethics at the NYU Grossman School of Medicine, who opposed the lifetime ban.

The lifetime ban was first eased six years ago, but only for gay and bisexual men who had not had sex with another man for at least a year — a rule that effectively continued to bar gay men if they were at all sexually active.

Loosening the ban was supported by prominent groups including the American Medical Assn. and the AABB. Opponents included the conservative Family Research Council, which argued the change was made “not for scientific or medical reasons, but for political ones.” At the time, the American Plasma Users Coalition expressed some caution, saying it could back the change only if it came along with a strong system to monitor blood safety.

Mark Skinner, formerly the president of the National Hemophilia Foundation, said that since then, the rollout of that monitoring system has made people who rely on blood products more comfortable with the shifts in donor eligibility.

The Advance Study “is an important piece of research that hopefully will give us comfort in advancing” further, said Skinner, who lives with severe hemophilia and became HIV-positive decades ago through a blood product. “If we are able to achieve this, then the whole blood system should be better off for it.”

Blood is now tested to detect HIV and other infections, but even the most sensitive tests are imperfect. If someone is exposed to HIV, it can take more than a week before it can be detected in their blood, a “window period” that has shortened over time. Experts from the AABB, formerly known as the American Assn. of Blood Banks, add that some diseases are not tested for in blood — including malaria — which has made it important to continue screening donors.

The restrictions are known as “deferrals” because possible donors who have done specific things, such as getting a tattoo or traveling to a place where malaria is endemic, are deferred from giving blood for a set amount of time afterward.

Eduardo Nunes, vice president of science and practice with the AABB, called deferrals “inherently kind of blunt instruments” that don’t capture the complexity of risk. For instance, to guard against mad cow disease, the FDA says donation centers should indefinitely bar donors who spent at least three months in the United Kingdom from 1980 to 1996.

“You could have spent a week in the United Kingdom in the mid-’80s eating nothing but raw cow brain” and still be eligible to donate, “or you could have been there for six months as a vegan, eating no beef products,” and not be able to do so, Nunes said. The rules are “clumsy at times.”

New HIV infections have fallen significantly since the 1980s, but gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men — dubbed “MSM” in federal guidance — are still hit hardest by the virus nationwide.

In Los Angeles County, nearly 80% of people living with HIV are gay and bisexual men, according to the county department of public health. Across the U.S., the lifetime risk of being diagnosed remains far higher for men who have sex with men than for straight men or women, according to a study published in the Annals of Epidemiology.

Critics of the blood donation restrictions argue, however, that the likelihood of infection for any individual is ultimately tied to whether they have engaged in risky behavior such as unprotected sex.

“We have rigorous studies that show what specific behaviors lead to HIV infection,” said Matthew J. Mimiaga, director of the UCLA Center for LGBTQ Advocacy, Research and Health. “It’s those specific behaviors that are placing people at risk.”

Some other countries have adopted a “gender neutral” or “individual risk assessment” approach. In June, health regulators in the United Kingdom started allowing blood donations from people who have been in a monogamous relationship with the same partner for the last three months, no matter their sex. Italy, Spain and Argentina assess individual donors based on specific behaviors, rather than the sex of their partners.

A new coronavirus threat is prompting Los Angeles County health officials to request a voluntary rollback of one of the freedoms fully vaccinated people only recently began to enjoy: no masks indoors.

Although the “blood community” has widely been open to the possibility, changing the way that donors are questioned is sensitive.

Alyssa Ziman, chief of transfusion medicine at UCLA Health, said blood centers need to find “a suitable way to determine who is a risk, but not alienate donors” who might be put off by probing questions about their sex lives. And screening needs to be efficient enough to avoid making the whole process of blood donation take too much time.

Blood banks have been suffering shortages as the country emerges from the COVID-19 pandemic, with demand for blood rebounding but donations still lagging. Even before the pandemic upended daily life, blood banks have faced longtime concerns about the aging of their most reliable donors.

After the pandemic hit, the FDA quickly eased some of its eligibility restrictions, allowing men to give blood if at least three months had passed since they last had sex with another man. Before that, the deferral period was a year.

The FDA said the change wouldn’t risk the safety of the blood supply because testing could detect HIV well within three months after infection. It also modified the rules for people with new tattoos or piercings, as well as sex workers and injection drug users, reducing their deferral period as well.

The risk of transmitting HIV through blood transfusion has plunged dramatically over the decades, with the odds now estimated at 1 in 2 million, according to a review published in Transfusion Medicine. Ziman said that the “blood community, as a whole, is in favor of using science to guide eligibility for blood donation.”

But it also has to grapple with the societal tolerance for risk, she said, and “after the HIV epidemic, the tolerance for risk, when it comes to transfusion-transmitted infections, is zero.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.