‘Cause for alarm’: COVID-19 hospitalizations worsen for Black L.A. County residents

Coronavirus case and hospitalization rates are worsening for Los Angeles County’s Black residents, a troubling sign less than a month after California fully reopened its economy.

Between mid-May and mid-June, the COVID-19 case rate over a two-week-period rose 18% among Black residents but declined 4% for Latino residents, 6% for white residents and 25% for Asian Americans. And the hospitalization rate for Black residents — who are less likely than other racial and ethnic groups to be vaccinated — grew by 11% while declining for Asian American residents by 12%, Latino residents by 29% and white residents by 37%.

Experts expressed shock and alarm at the rise in hospitalizations among Black residents. The trend underscores how — despite L.A. County’s devastating autumn-and-winter surge — many unvaccinated and susceptible people remain. Doctors warn the latest figures could be a prelude to rising deaths in the coming weeks and months.

“With low vaccination rates, plus the Delta variant, this can move actually very quickly to devastate the Black communities, particularly in our urban centers — again,” said Dr. Kirsten Bibbins-Domingo, epidemiologist at UC San Francisco. “When you see rising numbers of cases, you have to pay attention, because it means that those people are susceptible.”

The trends also underscore how, despite L.A. County’s respectable overall vaccination rates — which are on par with the statewide average — there remain many clusters of communities with much lower uptake of inoculations.

“It’s really quite uneven in our urban centers. Our Black communities have the lowest vaccination rates,” Bibbins-Domingo said. “What we’re seeing in L.A. is what we’ll see in other urban centers: The cases and the hospitalizations will rise among those who are unvaccinated,” and Black communities will be especially hard hit.

Making things worse is the swift spread of the Delta variant, which is possibly twice as infectious as the strains that spread around the world last year. “The Delta variant has really changed the game here,” Bibbins-Domingo said — a fact that should only further encourage younger people, who have been less enthusiastic about getting jabbed — to get vaccinated as soon as possible.

According to the most recent data, Black residents in L.A. County are roughly three times as likely as white residents to be diagnosed with the coronavirus, to be newly hospitalized with COVID-19 or to die from the disease.

“These disproportionately increasing rates of cases and hospitalizations among Black residents are cause for alarm,” said L.A. County Public Health Director Barbara Ferrer, “and they require strategic actions to prevent increased transmission and illness.”

In the two-week period that ended June 19, 46 out of every 100,000 Black residents in L.A. County were diagnosed with the coronavirus. The corresponding figures for Latino, white and Asian American residents were 22, 17 and six cases per 100,000, respectively.

Of the racial and ethnic hospitalization data recently released by the county, the only racial or ethnic group to see new coronavirus case and hospitalization rates worsen between mid-May and mid-June were Black residents.

For every 100,000 Black residents, 9.3 were newly hospitalized with COVID-19 in the two-week period that ended June 19. That was up from 8.4 in the two weeks that ended May 22. For Latinos, meanwhile, that rate fell from seven to five; for whites, from 4.3 to 2.7; and for Asian Americans, from 1.7 to 1.5.

More recent data, which will be released in the coming days, suggest that new coronavirus case rates have also started to increase among Latino and white residents.

Overall, the numbers underscore the continuing inequities of the pandemic. Black and Latino communities were hit particularly hard, in part because many residents in those communities had jobs that required they work outside their homes, putting them at greater risk of infection.

“These are communities who make up our essential workers — many who lived in multifamily units, and could not isolate in the comfort of their homes, and thus spread the disease to other close contacts. And they have suffered from years of under-investment, lacking access to health care, and living in polluted areas, impacting their overall well-being, resulting in chronic conditions that made them even more vulnerable,” L.A. County Supervisor Hilda Solis said recently.

“We owe it to those who [we] lost, and those who continue to suffer from these inequities ... to make it right,” Solis added.

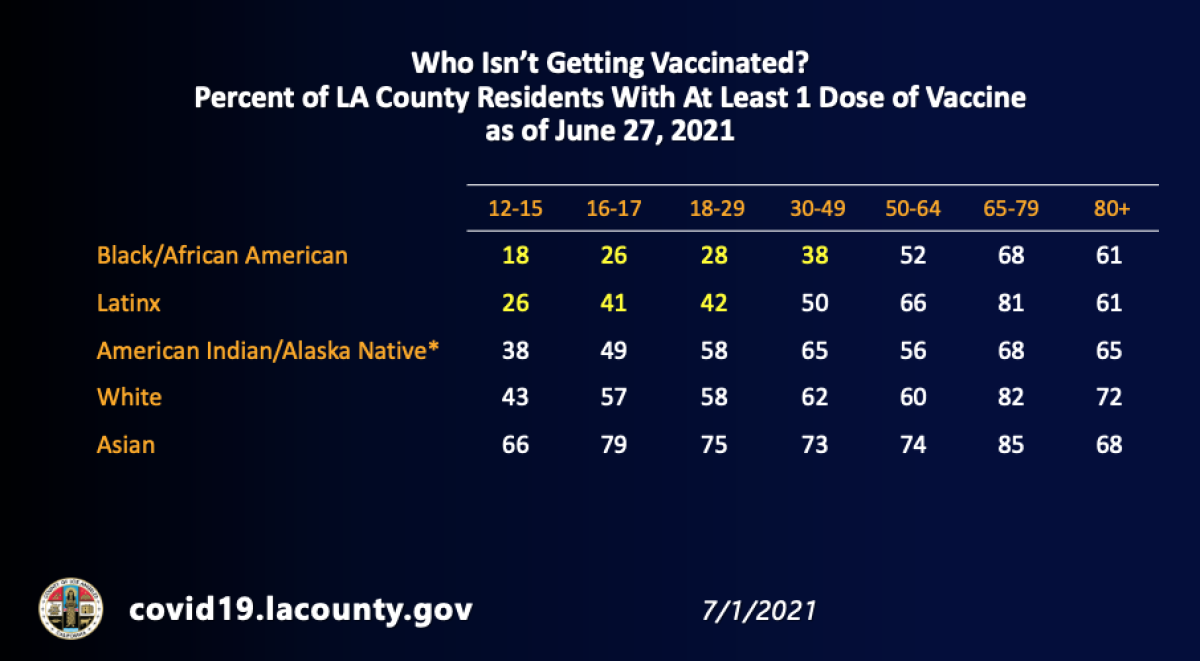

Black residents of L.A. County have among the lowest rates of vaccination among racial and ethnic groups in L.A. County.

The most recently available data show that 44% of Black residents 16 and older in L.A. County have received at least one dose of vaccine, as have 54% of Latino residents. By contrast, 65% of white, 61% of Native American and 75% of Asian American residents have received at least one shot.

The disparities are less pronounced among L.A. County’s seniors, perhaps because the vaccine has been available longer to people 65 and older, Ferrer said. Among seniors, 66% of Black, 67% of Native American, 76% of Latino, 79% of white and 80% of Asian American residents are at least partially vaccinated.

Officials are particularly concerned about disparities among young Black and Latino residents. Among the youngest adults — those up to age 29 — 28% of Black residents and 42% of Latino residents are at least partially vaccinated; that’s compared to 58% of white and Native American residents and 75% of Asian American residents.

Disparities also exist among other Black communities in California. In San Francisco, 59% of Black residents of all ages have received at least one dose of vaccine. By contrast, 65% of white, 71% of Latino, and 77% of Asian American residents in San Francisco are at least partially vaccinated.

But as the experience in San Francisco shows, it’s not impossible to improve vaccination rates among hard-hit communities. The vaccination rate among Latino residents in San Francisco is higher than it is for white residents — the opposite of the trend in L.A. County.

Part of that success has been the result of getting health workers and volunteers into stores and other places where people are gathering, and — one by one — encouraging people to take the vaccine. “There’s some ways in which we still have to lower the barriers [to get vaccinated] and make it easy for people to do,” Bibbins-Domingo said.

Black communities have also been the target of an insidious disinformation effort by anti-vaccination leaders, who have crafted false messages that reinforce a sense that Black people should not trust mainstream medical leaders, Bibbins-Domingo said.

Things that can help improve vaccination rates among Black residents include getting more doses into the offices of primary care physicians, who can answer questions one on one with their patients; and in places like churches or other community groups where trusted local leaders are promoting the importance of vaccinations, Bibbins-Domingo said.

“This is really a ground game at this point,” Bibbins-Domingo said. “It will be slow — it is not going to happen at the pace that we did it at the start of the vaccination campaign. But it is essential now, because when you see these rising cases, and you have a known variant that moves faster through communities, the urgency to get this done is really there.”

Ferrer has said that L.A. County has made strides in improving the availability of vaccines in hard-hit areas where there had been less resources to get vaccinated, such as through dispatching mobile vaccination teams and arranging for transportation to vaccination sites.

Promisingly, there has been a reduction in how likely a person is to get infected or die from COVID-19 based on the socioeconomic conditions of where they live in L.A. County.

But more needs to be done to get younger Black and Latino residents vaccinated, Ferrer said.

Coronavirus case rates among children also have started to increase, slightly, since June, Ferrer said.

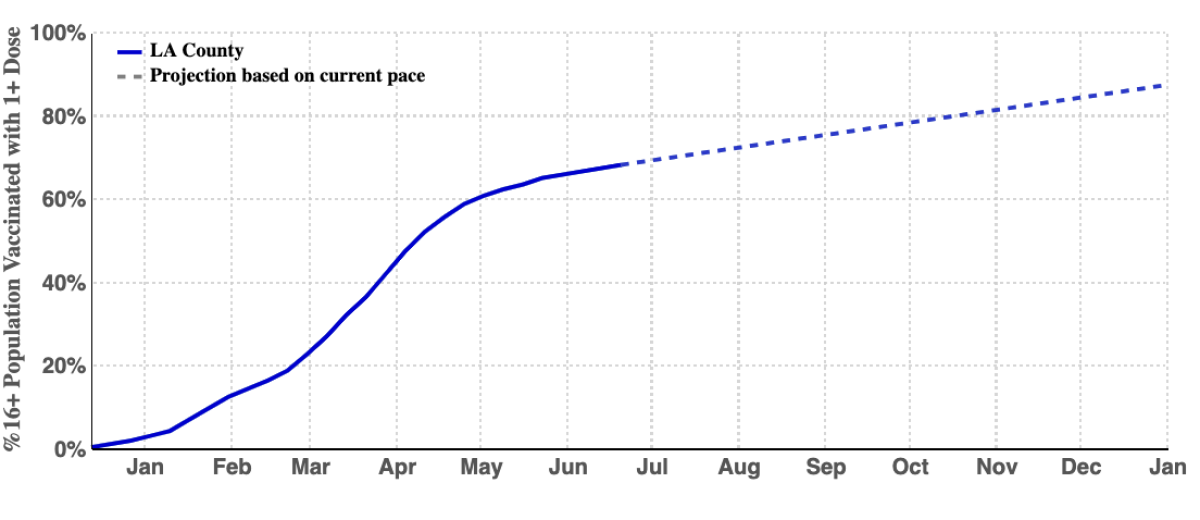

Dramatic week-over-week drops in weekly vaccination rates have slowed in recent weeks.

Nonetheless, the pace of vaccinations has proved to be disappointing to L.A. County health officials. Ferrer once held out hope that the county would continue giving 100,000 first doses of immunizations every week in a bid to reach “herd immunity” by the end of the summer, which would interrupt the ongoing transmission of the coronavirus broadly in the county. Ferrer has said L.A. County could achieve herd immunity when 80% of residents 16 and older are vaccinated.

But L.A. County has fallen short of that goal in each of the last four weeks for which data are available. For the seven-day period that ended June 27, about 69,000 first doses of vaccine were administered in L.A. County; the previous week, about 79,000 were administered; and the week before that, about 81,000.

At this rate, L.A. County would probably not reach herd immunity until, at the earliest, October.

Across L.A. County, 51% of residents of all ages are fully vaccinated. That’s lower than in San Diego County, where 56% of residents have been fully vaccinated, and in Orange and Ventura counties, with 53%. By contrast, San Francisco is reporting 68% of its residents as fully vaccinated; that figure is 66% in Santa Clara County, Northern California’s most populous county.

Across California, 51% of residents are fully vaccinated. Highly populated counties that lag the state’s overall rate include Sacramento (48%); Riverside, Fresno and San Joaquin (41%); San Bernardino and Stanislaus (38%); and Kern (34%).

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.