SAN DIEGO — Don White knew the desert: hot, dry, dangerous. He wanted to be ready.

The 68-year-old nature enthusiast from Culver City had volunteered again for the annual bighorn sheep count in San Diego County’s Anza-Borrego Desert State Park, one of the longest-running citizen-science projects in the country.

Held for 50 straight summers, it draws dozens of volunteers from all over California and beyond. They spend three days sitting under shade tarps in the triple-digit heat, collecting information for scientists monitoring the health of an animal that’s been on the federal endangered species list since the late 1990s.

After last year’s count was curtailed by the COVID-19 pandemic, the 2021 tally scheduled for this weekend drew so much interest there was a waiting list. Ninety volunteers were going to be split into small groups assigned to watch about 20 places in the park where thirsty rams, ewes and lambs typically come for scarce water at this time of year.

White’s spot, in the upper groves of Borrego Palm Canyon, is among the most challenging. Counting sheep there means hiking in about four miles, over and around boulders, and then staying put: watch for sheep from 7 a.m. to 5 p.m., sleep on the ground, get up in the morning and watch again. An experienced backpacker, White had counted there before.

He was concerned, though, about having enough water. Borrego Palm Canyon has streams that people using purifiers can drink from, but this has been a dry year, making those sources less dependable and harder to reach.

“Some of us feel a freedom in the desert that others find when they are sailing at sea or hiking in the high mountains.”

— Mark Jorgensen, former state parks superintendent

Two weeks ago, White and a colleague decided to hike in with bottled water and leave it there for the count. Water is commonly cached in other locations too, but volunteers usually do it in March, when it’s not so hot.

Coming back from the canyon just after noon June 19, not far from the trailhead, White collapsed and died. His colleague was hospitalized briefly, as was a firefighter who came to assist them.

The cause of death is under investigation by the county medical examiner, but it seems likely overheating played a role. It was 116 in Anza-Borrego that day.

State park officials didn’t wait for the autopsy results to reach their own conclusions. They canceled the bighorn count and initiated a review of its safety protocols.

The goal is to make improvements and provide “additional tools to maintain a safe environment for all,” the department said in a statement.

Many longtime volunteers, already saddened by White’s death, are upset about losing the annual count too — the camaraderie, the sense of accomplishment, the uninterrupted 50 years of data collection.

They said everybody who participates already feels safe because they are well-trained and understand the risks involved. Conquering the risks, in fact, is why some of them do it. They said there’s never before been a death or serious heat-related injury associated with the count.

They also worry that the review is being done as a pretext to cancel the program entirely. And they wonder if that’s what Don White would have wanted.

Animal lovers, adventurers

The count is done in the summer, around July 4, because it’s hot and dry then and the sheep have to come to where the water is, making them easier to spot. They typically need to drink every three days this time of year, which is why the count lasts that long.

It draws a mixture of people, many of them retired. Animal lovers and environmentalists. Adventurers who like a challenge. Desert aficionados.

“Some of us feel a freedom in the desert that others find when they are sailing at sea or hiking in the high mountains,” said Mark Jorgensen, a former state parks superintendent who’s participated in almost all the counts. “If you respect the desert and make preparations, it will allow you to pass through unscathed. But if you make an error, it can take you out pretty quickly.”

He was an 11-year-old Boy Scout camping in Anza-Borrego years earlier when a ranger came by for a talk. The ranger pulled a ram skull from the back of a Jeep and put it on the ground in front of the wide-eyed troop.

“It turned my light on,” Jorgensen said. “I still remember that spark of curiosity and marveling that a 200-pound ram could survive in such a harsh terrain.”

He got hired in the park as a college student to study desert bighorn sheep in 1972, one year after the count started. Soon he was helping to organize it and training the volunteers. After retiring in 2009 he stayed involved, and in 2014 was coauthor of a book, “Desert Bighorn Sheep: Wilderness Icon,” that draws from his decades of researching the animal and managing its habitat.

Once abundant in a range that extends from the U.S.-Mexico border to the San Jacinto Mountains in Riverside County, the sheep population plummeted to about 400 in the late 1990s due to habitat loss, disease, poaching, mountain-lion predation and other factors. It was put on the federal endangered species list.

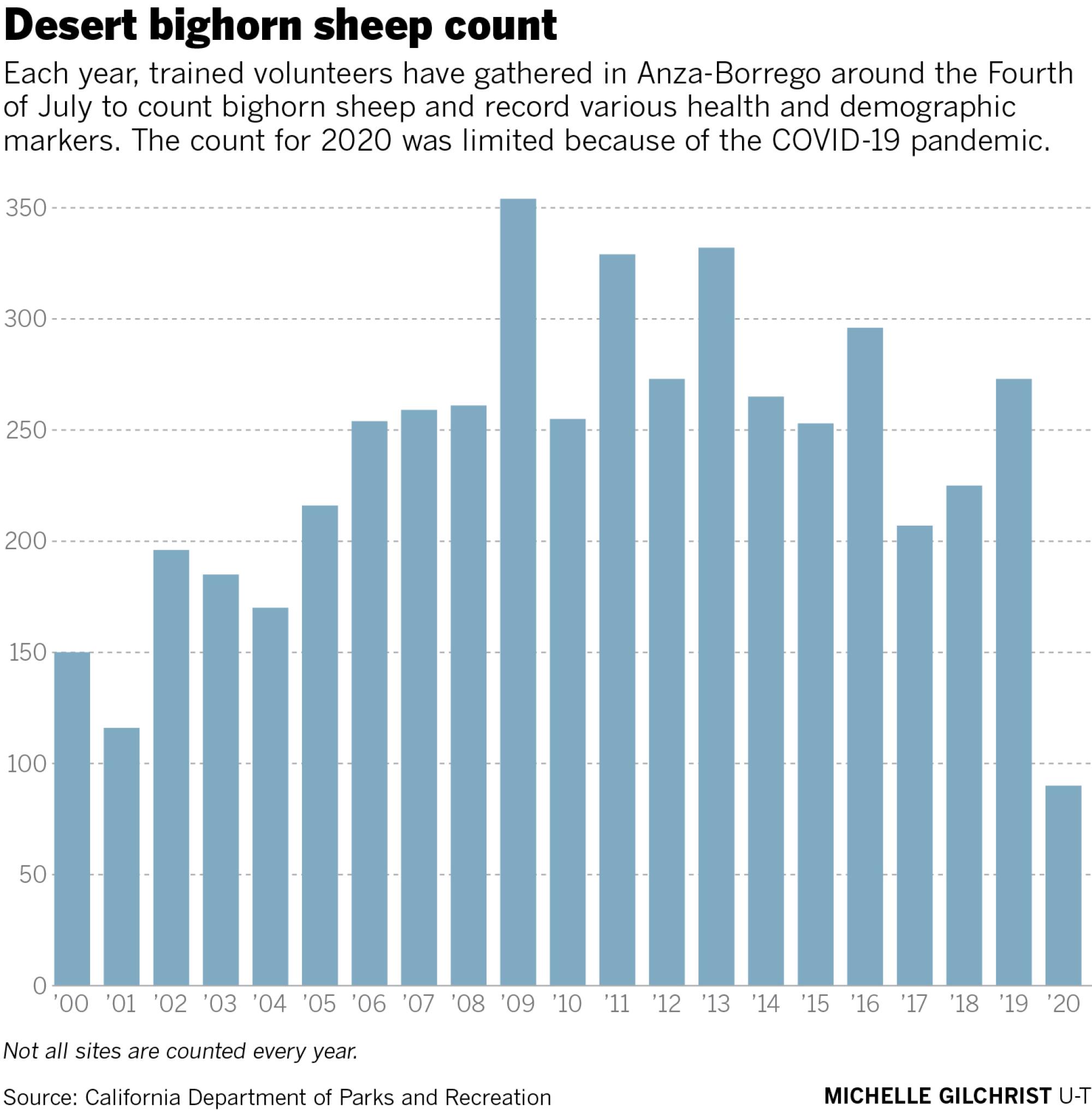

Recovery efforts led by the state Department of Fish and Wildlife have raised that total to about 1,000, with roughly 300 of them in Anza-Borrego. Officials credit information collected from aerial surveys, radio collars, field cameras — and the annual count — with helping them to boost the sheep’s chances of long-term survival.

“The count is a way for ordinary people to contribute to science, and to help out a really beautiful animal,” said Callie Mack, a 30-year veteran of the event from San Diego.

She and her partner, Phil Roullard, have worked several sites over the years and have learned that sometimes you hear the sheep before you see them. They dislodge rocks on their way down to the watering holes.

The spotters set up hundreds of yards away from the water so they don’t spook the sheep. Looking through binoculars, they note each animal’s sex, general age and distinctive markings (coloration, broken horns, scars, radio collar, ear tags). They look for any sign of injury or illness and watch what the sheep are eating.

They pay particular attention to the yearlings and to the lambs, born in the spring, one to each ewe. The number of youngsters provides a snapshot of survivability rates that can be compared with those from other years.

It’s tedious work, a lot of sitting and waiting without any guarantee of success. Sometimes counters in a particular spot see 75 sheep over the three days. Sometimes they get skunked.

Bees can be a problem. They’re drawn to water too, and sweaty people are moist. Counters have been stung.

“It can be miserable out there,” Mack said. “Sweat is dripping down, you’re baking, and you’re asking yourself, ‘Why am I doing this?’ Then you see sheep and you get excited and you forget how hot and tired you are.”

Safety first

All new sheep counters go through an orientation that includes a little information on bighorn natural history and a lot on safety.

They’re told about heat exhaustion and heatstroke, how to say hydrated, what to do in an emergency.

“We really make people understand that if you get lightheaded, if you’re feeling sick, we would prefer you get back to camp,” Jorgensen said. “Your safety is more important than counting sheep.”

He said there have never been any serious injuries during the count — a broken ankle one year, a separated shoulder another, a handful of minor heat exhaustion cases that did not require hospitalization.

The counters work in teams, in case one of them encounters problems. Most of the teams set up at sites that are close to their cars, which can take them to safety if need be. Cars offer plenty of room for ice chests full of beverages and cooling scarves too.

At night, in between counting sessions, many of the participants go into the town of Borrego Springs and stay in rented condos or motels with air-conditioned rooms, swimming pools and bars where bets get paid off for spotting the first sheep that day.

Conditions are rougher for those backpacking into the remote sites. More planning is required, and there’s less room for error. Generally speaking, it’s a younger person’s game, for people like Tyler Webb, 39, of San Diego, who has been making the overnight treks for about five years and had planned to be in Rattlesnake Canyon for this year’s count.

He worked with White, the fallen counter, in Borrego Palm Canyon in 2018. A year later, he helped White cache water there in advance of the tally.

“His backpacking philosophy matched mine,” Webb said. “Pack light. Everything you carry slows you down, and especially in the desert it takes a lot out of you.” They felt the same about clothing too: Long pants and long-sleeved shirts for protection from the sun, rocks and brush.

They shared a passion for the challenge too, and for “seeing a side of the desert most people never get to see,” Webb said. He once spotted a rare ringtail cat.

When they were together, White talked about other citizen-science adventures, Webb said: the annual Hawkwatch in Anza-Borrego, held in the spring during the migration of Swainson’s hawks, and BioBlitzes, gatherings to find as many species as possible in a certain area over a short period of time.

“I can’t claim to know Don outside the sheep count and hadn’t spoken with him since the 2019 edition,” Webb said. “From my experiences with Don, he was a great guy and I am saddened by his passing.”

An uncertain future

Many of the counters expected some kind of reaction from park officials after White died. It’s what bureaucrats and lawyers do. Maybe a mandatory lecture on safety, they thought. Maybe barring counters from the remote locations.

But not a cancellation.

“People had bought plane tickets and made hotel reservations,” Mack said. “The restaurants in town were expecting more customers. I don’t think [park officials] know what this count means to people. Or maybe they just don’t care.”

Gary Jones, a 20-year count veteran, said in an email to park officials, “I am, as was [Don White], 68 years old, and believe that life should be lived to the fullest. Had Don wanted to be at home watching golf on TV, he would have done that.”

Jones noted that he carried water to one of the remote sites in the spring in preparation for the count. “If anything had happened to me,” he wrote, “I certainly would not want the long history of the count to end (or even be interrupted) because of it.”

Others were more sympathetic to the decision-makers.

“I’m disappointed, but I understand the reasoning behind it,” said Gloria Kendall, a longtime counter from Escondido. “One of our own lost his life, another one could have, and if they feel they need to do a safety check, I support that.”

She too shares a concern voiced by many about the future of the bighorn tally. “I like the count and I think it’s an important thing,” she said. “I hope they don’t cancel it altogether.”

In its statement, the State Parks department talked about improving the program, not scuttling it. But it also called the count “only one piece” of the overall recovery plan for the bighorn sheep.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.