How worried should I be about the COVID-19 Delta variant?

As the California economy reopens, officials are issuing warnings about the Delta variant of the coronavirus, which is a risk to people who have not been vaccinated against COVID-19.

Here is what you need to know:

What is the Delta variant?

The Delta variant, also known as B.1.617.2, was first identified in India.

Nationwide, between May 9 and May 22, the Delta variant comprised less than 3% of genomically sequenced coronavirus samples. Between June 6 and June 19, that proportion rose to more than 20%.

In California, the Delta variant has grown from comprising 1.8% of analyzed coronavirus samples in April to 4.8% of them in May.

The Delta variant is now the fourth most-often identified variant in California. Still at the top is the Alpha variant, first identified in the U.K. (also known as B.1.1.7), which represents 58.6% of samples.

Some counties report those data individually. Northern California’s most populous county, Santa Clara, for instance, has confirmed 58 cases of the Delta variant.

And in Los Angeles County, officials say they identified 64 cases of the variant among residents from late April to early June, with most of those confirmed within the last few weeks.

California is contending with what could be the most contagious coronavirus variant to date, prompting officials to warn that residents face significant risk if they are not vaccinated.

Why is this variant a concern?

While the Delta variant is known to be more infectious, experts differ on whether they think it causes more severe illness than other coronavirus strains.

“More young people are getting infection, right, and they’re winding up in the hospital. That’s not a good sign,” said Dr. Eric Topol, director of the Scripps Research Translational Institute in La Jolla.

By contrast, with the conventional strains, young people — which Topol said refers to those younger than 40 — were rarely in the hospital.

But, Topol added, there’s no evidence the Delta variant is more likely to cause death than other variants.

Other experts are also not convinced that the Delta variant is more likely to cause more severe disease.

COVID-19 hospitalizations in the U.K. are actually growing more slowly than new cases — meaning the chance an infected person has of being hospitalized has been reduced, said Dr. Monica Gandhi, an infectious diseases expert at UC San Francisco.

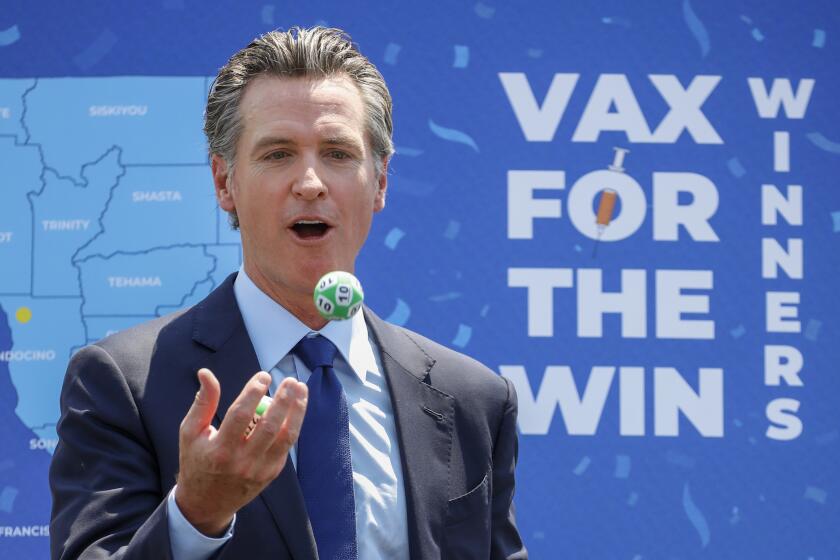

Though it is impossible to say for sure, some suggest the state’s $116.5-million incentive program probably sparked renewed interest in getting a shot.

What is the Delta variant’s effect on children?

One promising sign, Gandhi said, is that there doesn’t seem to be any increased risk to young children.

Young children already are less likely to contract the coronavirus because they have far fewer proteins called ACE2 receptors in their noses that the coronavirus needs to access to infect the body.

How about vaccine effectiveness?

Vaccines that have been shown to be effective against the Delta variant include the two-dose Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine and the two-dose AstraZeneca inoculation — which is not yet authorized for use in the U.S. but is in widespread use in the U.K. and similar to the one manufactured by Johnson & Johnson.

One recent study found that getting both doses of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine was 88% effective against symptomatic disease caused by the Delta variant and 96% protective from hospitalization.

California is particularly well placed to deal with the Delta variant, with 73% of the state’s adults having received at least one dose of vaccine — even better than the respectable national rate of 66% — and because many other Californians have survived COVID-19 from past surges.

Experts say about most Americans will need to be vaccinated to bring the coronavirus pandemic under control. Track California’s progress toward that goal.

Does this threaten the state’s reopening?

Experts say no — largely because of the number of people now vaccinated. California also has a significant number of people who have lingering immunity to the coronavirus because they’ve survived past infection. (Officials urge that people with past infection still get immunized, as immunity through inoculation is better and longer lasting that immunity acquired through surviving infection.)

The concern is for the minority of the population who have not been vaccinated.

“We will never see the surges that were overwhelming our hospital system,” said Dr. Robert Kim-Farley, medical epidemiologist and infectious diseases expert at the UCLA Fielding School of Public Health. “There just is not enough people susceptible at this time to create those magnitudes of surge.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.