Do you love L.A.? Learn these other songs too

Los Angeles’ jukebox is huge. You would run out of quarters, even virtual quarters, long before you ran out of songs about L.A. and California.

Each decade racks up its hits: for the 1960s, it’s the Flying Burrito Brothers’ “Sin City”; 1970s, Los Tigres del Norte’s “Contrabando y Traición”; 1980s, Steely Dan’s “Babylon Sisters”; 1990s, Dr. Dre and Tupac Shakur’s “California Love”; and 2000s, Jay-Z and Beyonce’s “Hollywood.”

A Times project a couple of years ago sussed out “50 Songs for a New L.A.,” all of them since 1969.

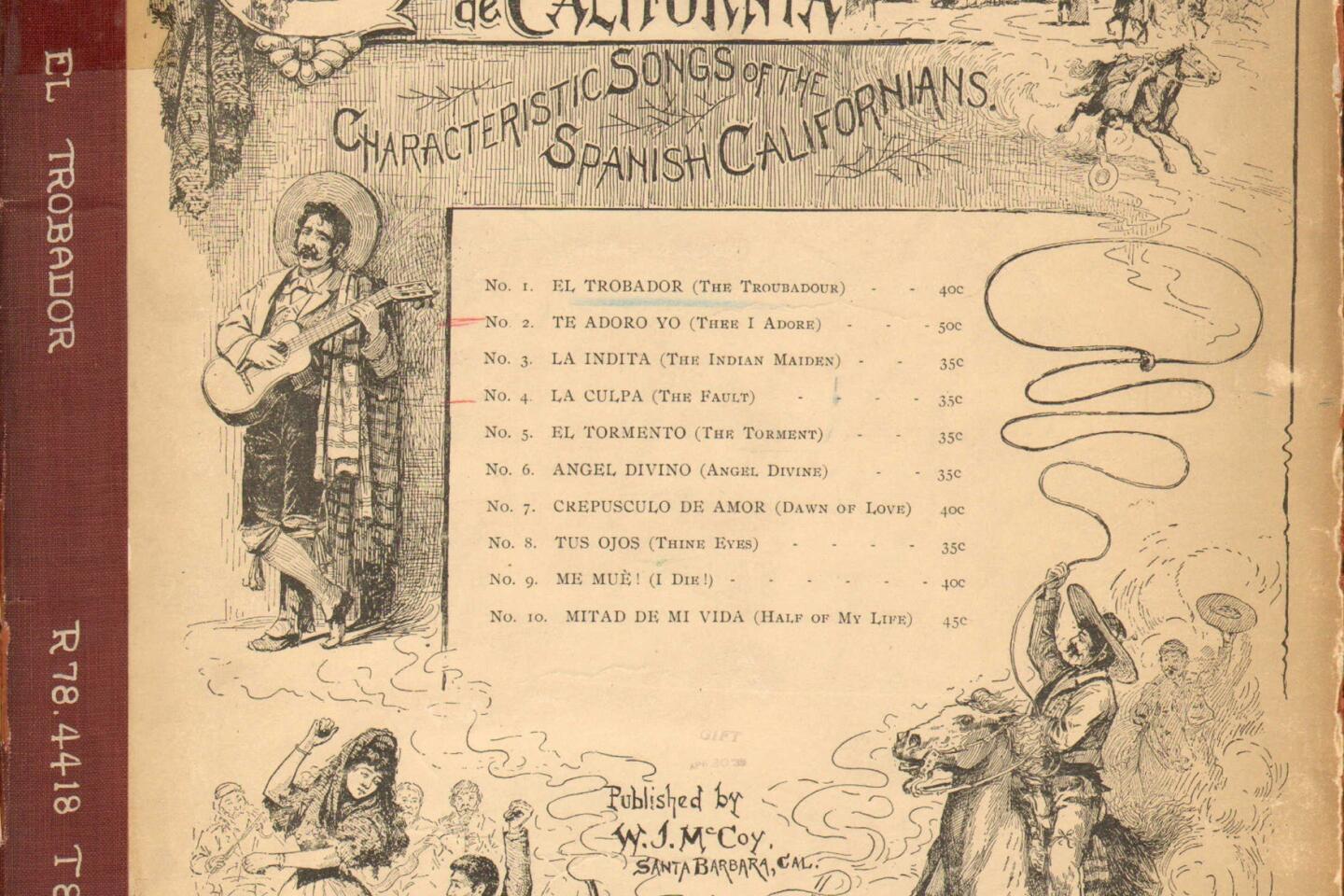

But thousands of people have been making music in and about L.A. for hundreds of years — Native American, Spanish, Mexican and Californio music. One of L.A.’s true characters, Charles Lummis — ethnographer, adventurer, pal of Teddy Roosevelt, editor, lover — did history the astounding favor of recording, in 1904 and 1905, more than a hundred Spanish-language California songs by singers who remembered them, principally Señorita Manuela Garcia. The Autry Museum digitized many of these, and you can listen to them here.

The huge hole in the record of L.A.’s musical storytelling is because so many old tunes were sung in the streets, at home, at ceremonials. They weren’t recorded and sometimes died when the singers died, leaving L.A.’s sheet-music story tilted, like history itself, toward the tellers and the scribes.

So I’ll see those 50 years of L.A. songs and raise you by another, oh, 100 years of songs on paper.

Explaining L.A. With Patt Morrison

Los Angeles is a complex place. In this weekly feature, Patt Morrison is explaining how it works, its history and its culture.

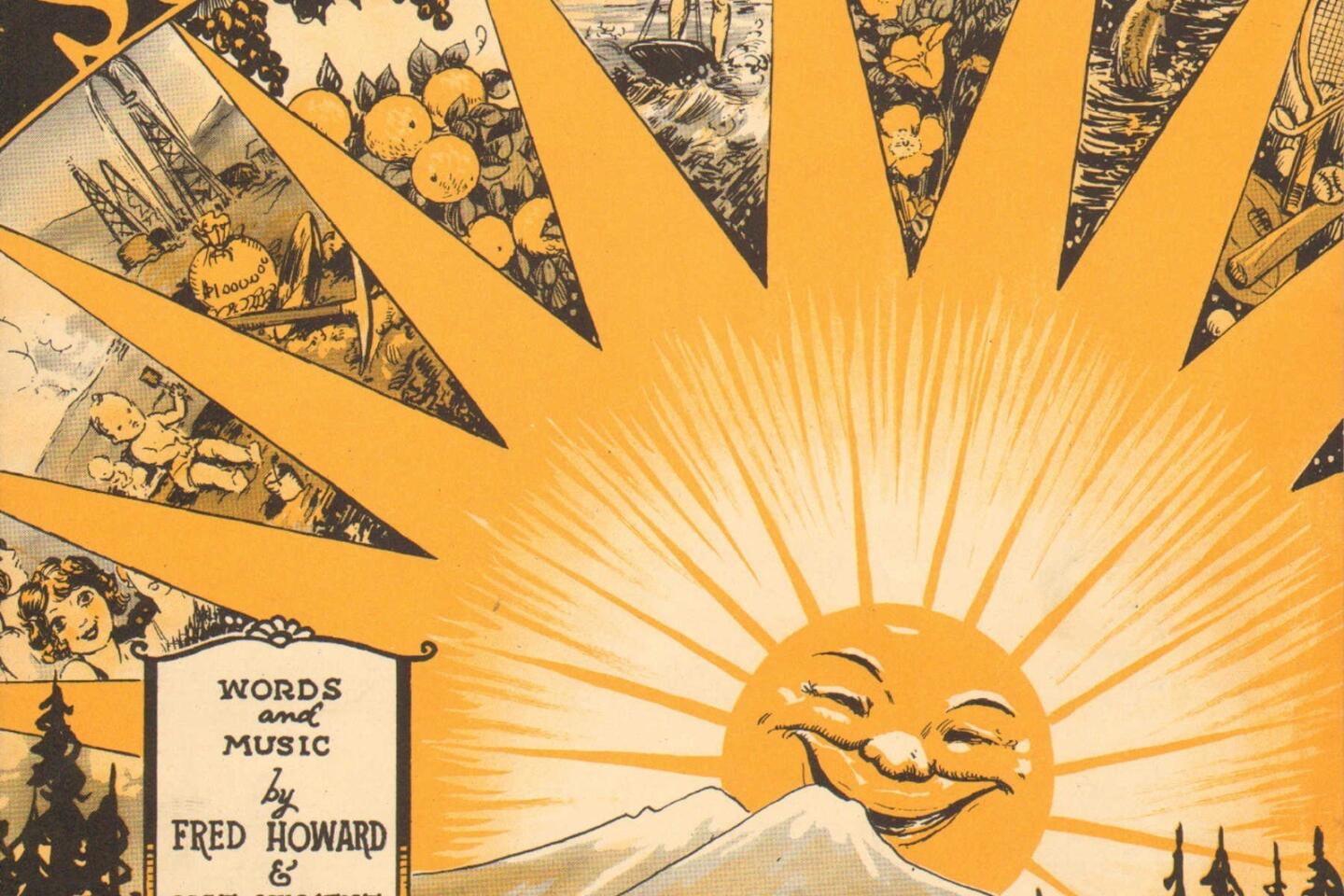

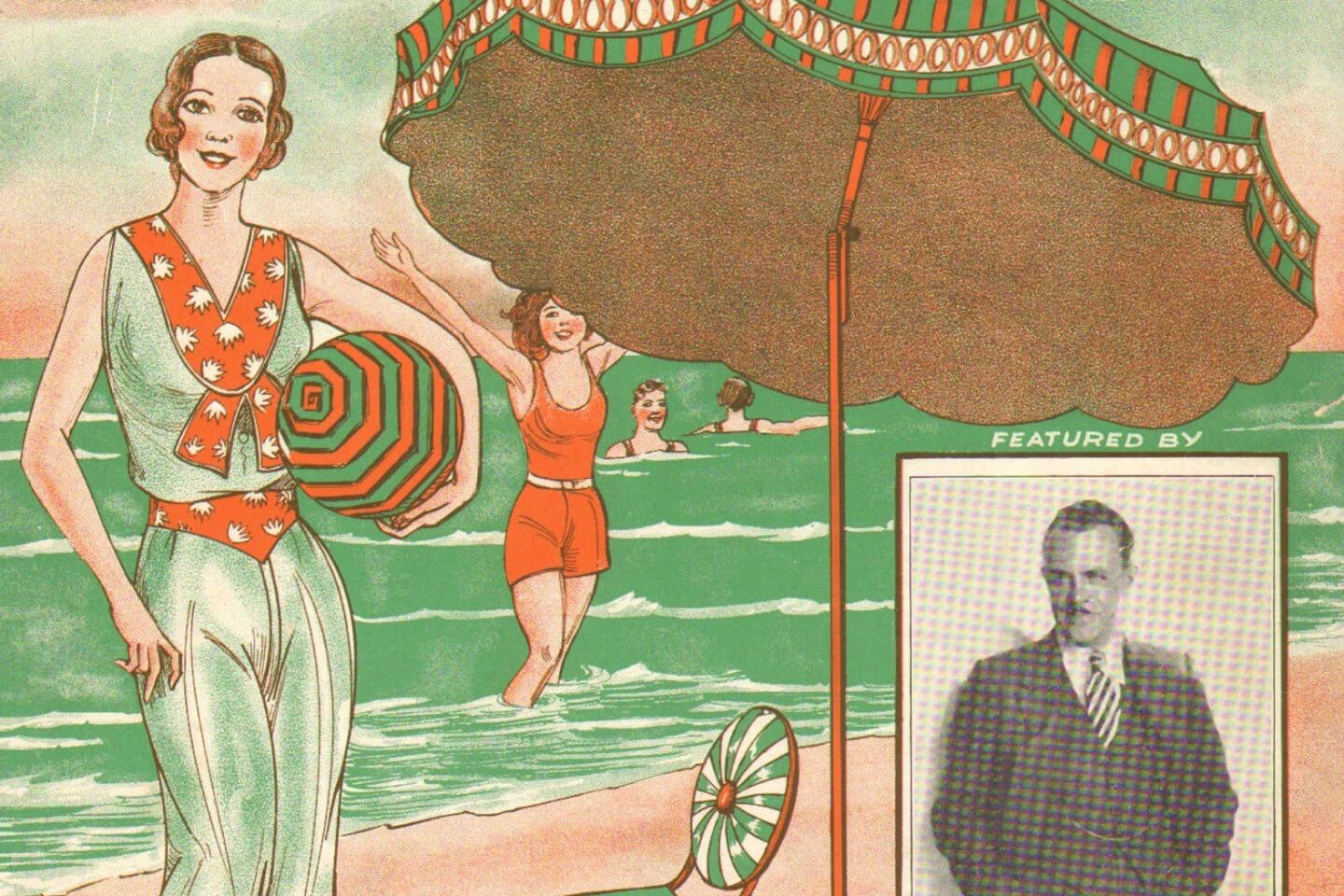

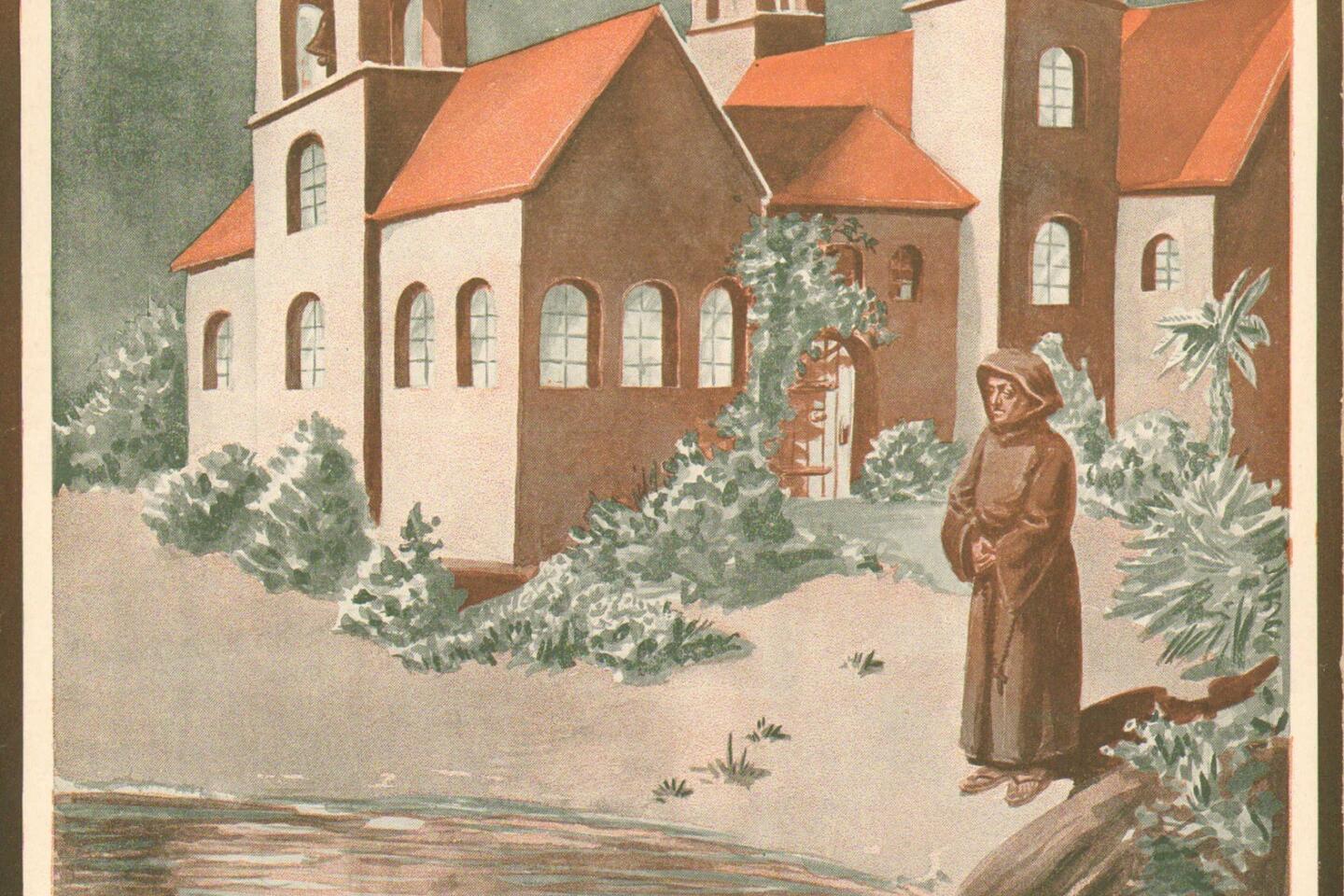

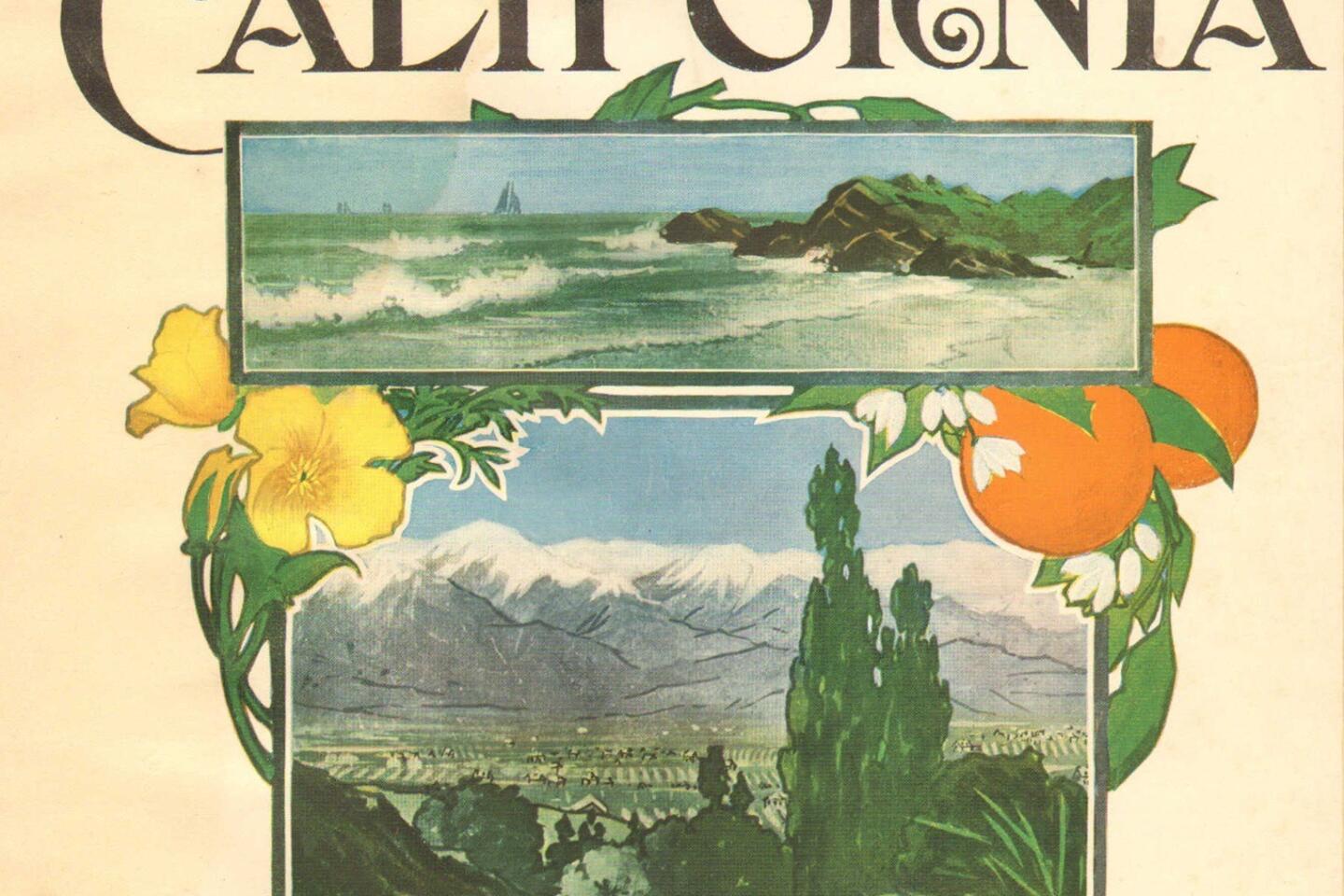

Sheet music was the MP3, the streaming playlist, the sing-it-yourself soundtrack of the Los Angeles illustrated with orange groves and dream-girl maidens and sunshine. It promoted a fantasy L.A., one bleached of its ethnic backstory into a blandly mythologized dreamscape of whiteness and prosperity, showing to the world a delightsome city of carefree song.

You can find many of these works in “Songs in the Key of Los Angeles,” the illustrated book Josh Kun wrote using the Los Angeles Public Library’s deep collection of California sheet music. They cross almost 100 years, most of those the great boomer-booster decades of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

“I started thinking of the sheet music as a version of orange-crate art: seductive visual art of healthy landscapes” that sold the music while selling the city, Kun said. Tourists who bought a ticket for a tour of the orange groves and beaches and foothills received sheet music with the ticket. They took it home and played its tunes for their friends and neighbors, who sometimes decided to see this paradise for themselves — and never left.

Lyricists were hard-pressed to match words to image. Nothing really rhymes with “orange,” and at the time, some locals pronounced “Los Angeles” so that the last syllable rhymed with “cheese,” not a word to hang a Chamber of Commerce campaign on. Decades later, Arlo Guthrie — whose father, Woody, was briefly a radio DJ here in the 1930s — used the pronunciation in an unorthodox chorus about smuggling cannabis: “Comin’ into Los Angeleees/bringin’ in a couple of keys.”

Some songs were written by people who hadn’t laid eyes on L.A., and some were in the cloyingly poetic style of the period. The forgotten and forgettable “Little Ol’ Los Angeles,” in 1914, warbled, “There’s a place that ev’ry wand’rer fondly hopes and longs to see. Ere life’s fitful dream is over and he wakes in eternity.” What a contrast to the boom-de-ay gusto of “California, Here I Come” just seven years later.

Kun was struck by how many sheet-music covers showed L.A. as a woman — not a brazen flapper but a demure sweetheart framed by flowers or citrus. In “the gendering of L.A., the idea of L.A. as a queen, a city of queens, L.A. sold itself as a gendered feminine city.”

Clubs, cafes and restaurants commissioned their own sheet-music tunes. The 1912 “People’s Aviation Meet” at the South Bay’s Dominguez Field was celebrated in sheet music (“Since the merry old days of the dear Peter Pan, oh gee! I have wanted to fly”). And in short order, hymns and anthems sang the glories of Avalon, Pasadena, the Palos Verdes Peninsula, Long Beach and San Bernardino. Sheet music of the most famous suburb song of all, “The San Fernando Valley,” sung by Bing Crosby, shows the Valley with a crop of saguaro cactus, found only in the Sonoran desert hundreds of miles away. The songwriter lived in Sherman Oaks, so he knew better, but obviously the illustrator did not.

Black L.A.’s music was supercharged by the arrivals of Jelly Roll Morton and Kid Ory, two celebrated New Orleans jazz musicians, and in 1921, Ory and the Sunshine Orchestra became the first Black Americans to record instrumental jazz, on the new Sunshine label.

Among my sheet-music favorites is what’s perhaps the earliest published song about California, from the Gold Rush year of 1849. It’s a “comic song” that could be repurposed as a cautionary tale for land speculation or for Hollywood — or really, for any age when California entices, then disappoints. In “California as It Is,” a prospector sings that he has “been to California and I haven’t got a dime; I lost my health, my strength, my hope, and I have lost my time.”

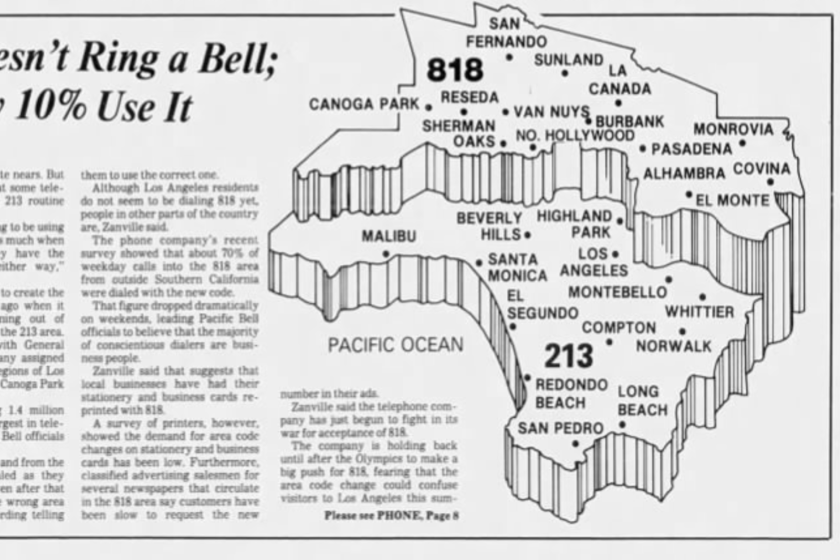

In Southern California, an area code can say a lot about a person. Are you a 310, a 213 or a 323? What does it mean if you have a 562 or an 818?

You were wondering when I was going to get around to this one, weren’t you? “I Love L.A.”

Isn’t that L.A.’s official city song? No. The mayor’s office told me that the city cultural affairs office told them that L.A. had no official city song. We’ve been shilly-shallying around on this since the Eisenhower administration. In the ’50s, the hemi-demi-semi-official song was “Angeltown.” A Los Angeles Times columnist supposedly wheedled the songwriters who wrote “Que Sera, Sera” and the “Bonanza” theme into composing it. And it sounds like the kind of song born less from inspiration than from provocation.

As for Randy Newman’s “I Love L.A.,” it burst onto the city in a Nike ad during the 1984 summer Olympics, but official L.A. just couldn’t bring itself to embrace officially a cheeky lyric with a “bum … down on his knees” and that “big nasty redhead” riding shotgun.

I was at City Hall right after the Olympics when the City Council president honored Newman and his song as “the closest thing we’ve had so far” to a theme song. As I wrote then, “it is not a song that makes you want to put your hand over your heart, but L.A. is not that kind of city, either.”

Los Angeles County has an official song, “Seventy-Six Cities.” It debuted for L.A. County supervisors in September 1965, performed by Sing-Out ’65, a troupe later known as Up With People, which explains why it has the tempo and lyrics of a camp singalong. If it were played at the start of every Board of Supervisors meeting, we’d have a new county anthem quick.

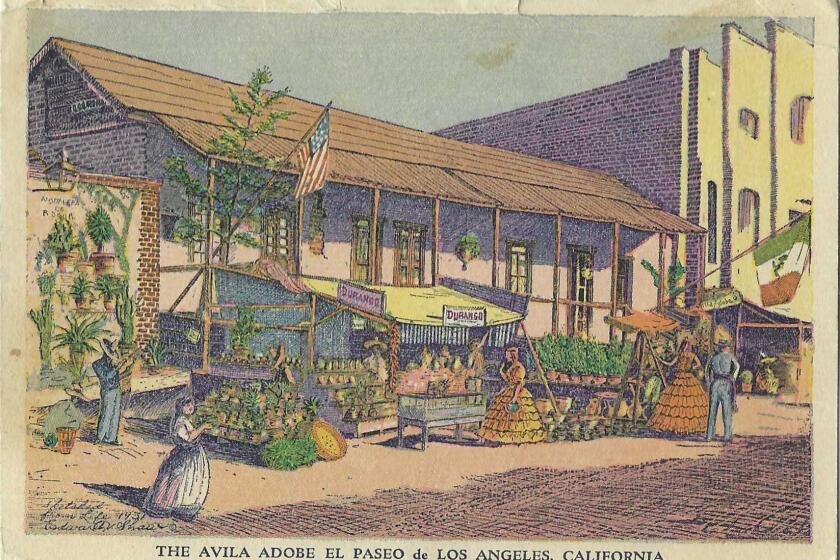

Native American settlements were first, and then the rancho system -- Spanish then Mexican land grants throughout California -- were built atop and near those settlements and still shape our geography and place names.

For the love of Lufthansa! Even LAX has an official song. It exists in two different versions — virtually the same music and both with a country-western sensibility that seems a little pokey for the Jet Age.

And now we come to the Golden State. Ask the random Californian about the official state song and the answer would likely be “California, Here I Come.” Well, who wouldn’t?

The official song is “I Love You, California,” lyrics by “Daddy” Silverwood, a haberdasher whose clothes dressed Southern California gentlemen for nearly 100 years. Wikipedia says confidently that “I Love You, California” is played at the funerals of California governors, but it sounds too dissonantly peppy for that. Just to check, I watched the C-SPAN coverage of Ronald Reagan’s funeral service and burial. I heard a lot of solemn and patriotic music, but I didn’t hear “I Love You, California.” It’s a song better suited instead to the Jeep ad that it scored almost 10 years ago.

As for this town, Kun figures that “the reason why a single song has never worked in L.A. is because of the impossibility of singularity here. The more you try to create a monolithic or single take on what Los Angeles is, some sound, some image that covered everything, the more you realize how impossible it is. … I love that every neighborhood, every community, every generation has its version of what the true L.A. song is.”

Maybe it’s time we stopped looking for the perfect song and made ours a chorus of songs. Get fixated on any one tune and you get ossified in that moment, like a creature mired in the La Brea Tar Pits.

The 1965 search for a modern L.A. song attracted hundreds of entries but none, that I know of, extolling smog, not even to rhyme it with fog or agog. Some unknown thought L.A.’s anthem should boast of “Sandy beaches, free of leeches.”

Heck — today that might win.

L.A. is a place like no other. You’ve got questions. Patt Morrison probably has answers and can definitely find out.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.