State Bar admits ‘mistakes’ in handling complaints against ‘Real Housewives’ Tom Girardi

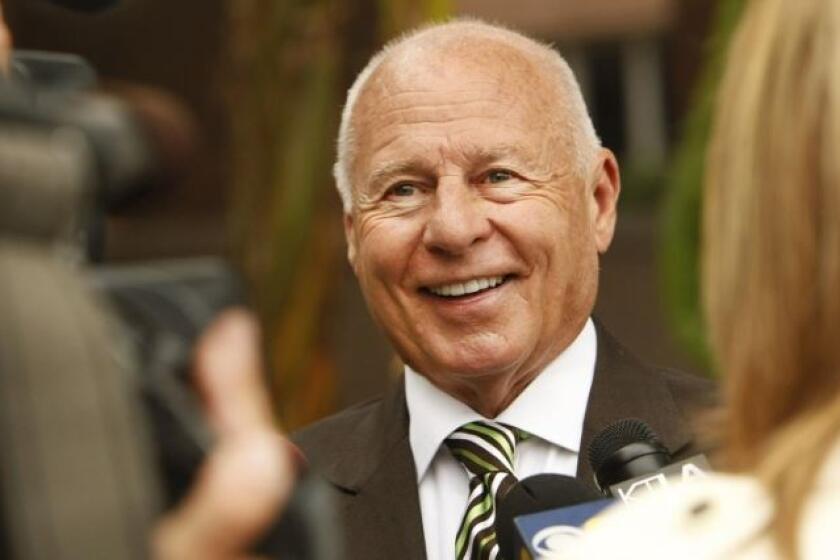

The State Bar of California acknowledged this week that its investigators had mishandled years of complaints against disgraced legal titan and “Real Housewives of Beverly Hills” cast member Tom Girardi.

The stunning public admission by the agency that regulates the state’s legal profession comes after a Times investigation published in March described how Girardi had kept his law license pristine despite numerous complaints against him at the State Bar as well as more than 100 lawsuits against him and his firm, many of them alleging misappropriation of funds.

The article detailed how Girardi cultivated close relationships with bar employees by treating them to wine-soaked lunches at Morton’s, casino parties in Las Vegas and private plane rides.

The regulatory agency’s Board of Trustees said in a news release Thursday that an audit of the L.A. power broker’s disciplinary file “revealed mistakes made in some investigations over the many decades of Mr. Girardi’s career going back some 40 years and spanning the tenure of many Chief Trial Counsels.”

The audit conducted by an outside consultant “identified significant issues” in the “investigation and evaluation of high-dollar, high volume trust accounts,” the bar said.

The announcement was highly unusual for the State Bar, which rarely comments on its investigations, and a testament to how thoroughly the downfall of the wealthy and politically connected Girardi has shaken the legal community and the organization tasked with protecting the public from unscrupulous attorneys.

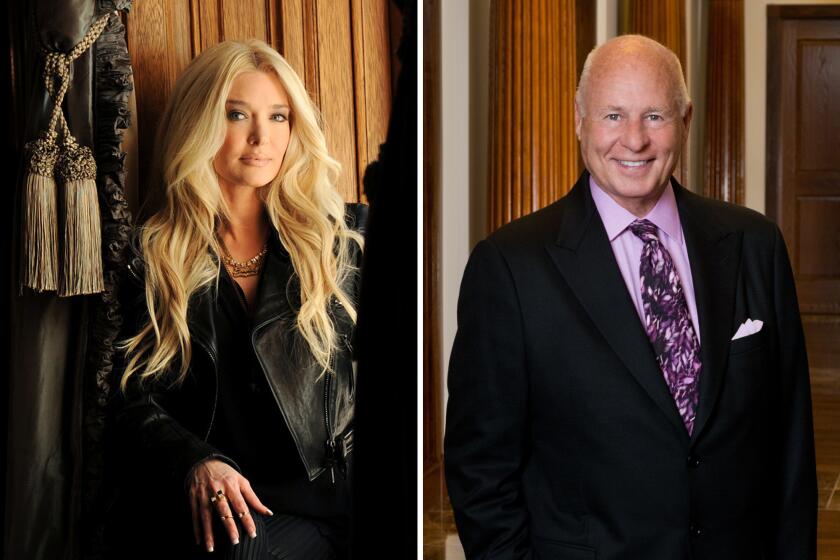

Tom Girardi is facing the collapse of everything he holds dear: his law firm, marriage to Erika Girardi, and reputation as a champion for the downtrodden.

But some in Sacramento said the bar needed to go even further to address the Girardi scandal. Two politicians with agency oversight demanded that the audit be made public while also calling for a further accounting of how Girardi eluded discipline.

“We are going to have to dig deeper,” state Sen. Tom Umberg, the Orange County Democrat who chairs the Senate Judiciary Committee, said in an interview.

For decades, the 82-year-old Girardi seemed an immutable force in the plaintiff’s bar in California and beyond, winning huge settlements and judgments against drug companies and toxic polluters, including in the case immortalized in the film “Erin Brockovich.” In more recent years, he also enjoyed pop culture notoriety on “The Real Housewives of Beverly Hills” alongside his now-estranged wife, pop singer Erika Jayne.

Friends and peers were shocked when his well-respected firm, Girardi Keese, collapsed last year. Then evidence began piling up that he had misappropriated millions in settlement money from vulnerable clients — including widows, orphans, a burn victim and his family — in what one colleague characterized to a federal judge as a long-running Ponzi scheme.

Girardi and his law firm have since been forced into bankruptcy, and a court-appointed bankruptcy trustee has said in court papers that he owes more than $56 million to creditors, former clients and lenders.

The bar did not say whether the specific mistakes uncovered in the audit were related to Girardi’s currying of favor with staff or trustees, nor did the agency say whether its findings resulted in the discipline or termination of employees.

The audit was performed by Alyse Lazar, a Thousand Oaks attorney who was a supervising prosecutor for the bar in the 1990s and who already conducts random reviews of closed discipline cases, according to Teresa Ruano, a bar spokeswoman. Lazar, who declined to comment, was ultimately paid more than $25,000 for reviewing the Girardi complaints, which began March 15.

Ruano said she could not disclose specific information about the number or nature of the complaints that were part of the audit and maintained that the final report was shielded by attorney-client privilege.

Tom Girardi and his firm were sued more than a hundred times between the 1980s and last year, with at least half of those cases asserting misconduct in his law practice. Yet, Girardi’s record with the State Bar of California remained pristine.

“The details of the audit are confidential,” Ruano said.

The two state lawmakers who chair a pair of legislative committees that oversee the State Bar told The Times that it was imperative for the audit to be released to the public.

“This is not like a national security issue,” Umberg said. “The revelation of this ... will help us to protect consumers. Unless the nuclear codes are somewhere in there, I think they could release most of it.”

Umberg, who is also a practicing attorney, said transparency was essential to restoring the credibility and trust of the bar. He noted that fellow attorneys and members of the community repeatedly ask how lawmakers will respond to the apparent lapses in discipline in the Girardi case.

“The Girardi debacle — it’s an embarrassment to the entire profession,” Umberg said. “The question is: Have there been other failures of a similar nature?”

Assemblyman Mark Stone (D-Scotts Valley) said the audit’s findings exposed “pervasive and institutional shortcomings” in how attorneys are regulated.

Stone, who chairs the Assembly Judiciary Committee, likewise called for disclosure of the audit report and demanded “a full audit of the Girardi case by an outside entity.” Such a review would be used by the Legislature, Supreme Court and the public to illuminate what went wrong, he said.

“I am very concerned that the Bar made numerous errors and oversights in the Girardi case over a four-decade period,” Stone said. “These mistakes endangered the public, allowed Girardi to prey on vulnerable clients, and have seriously undermined confidence in the competence of the State Bar.”

Numerous trustees of the bar declined to comment to The Times. According to the news release, the trustees have asked that bar employees “investigate new and innovative means of regulating and monitoring attorney-client trust accounts to prevent misappropriations from occurring in the first place.”

The agency said it was also considering the hiring of accounting experts to examine the “high-dollar” client trust accounts — the bank accounts attorneys use to hold clients’ money — as well as installing automated tools to help identify “patterns of behavior that could signal possible misconduct.”

“We must use lessons learned to strengthen the State Bar’s rules, policies and procedures to avoid replicating problems of the past,” said the board’s chair, San Francisco attorney Sean SeLegue.

The bar is trying to disbar Girardi, formally accusing him of misappropriating millions in client funds, dishonesty and other unprofessional conduct. He was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease this year, and his brother, who acts as his legal guardian, has told the bar through a lawyer that Girardi will not practice law again and does not plan to contest the proceedings.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.